Entropy is a dynamic that recurs across multiple disciplines, including science, politics, religion and even finance. It encapsulates the idea that systems and institutions tend towards disorder, fragmenting and breaking down over time. However, that doesn’t mean that everything is ultimately headed towards chaos. In some cases, it seeds new orders and creates new winners.

In this note, I’ll argue that rising entropy is a force reshaping many systems, including US culture. And I’ll explore the implications for long-term growth investing in general and some of our portfolio companies specifically.

But first, let me set the scene by defining three premises to work from:

1. Change drives growth

I’ve previously discussed how Indian IT outsourcing companies directly benefited from the bursting of the internet bubble and went on to grow at a 40 per cent compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for the ensuing decade. And how IBM endured a world war and a series of economic recessions to grow at least 10 per cent in 42 out of 50 years from 1935 to 1985.

The point is that the root cause of any growth business is change. Dynamism. Disruption. Sometimes this can feel counterintuitive because some change might not feel particularly constructive. But it’s change that drives growth.

So, we study change.

2. System change drives monumental growth

Some change occurs at the micro level. A new product can shift the competitive dynamic within a category. A change in Walmart’s shelf space can give one brand an advantage. A restructuring can alter a company’s long-term cash flow profile. These types of change can create wonderful investment opportunities. But they’re fairly linear, and the number of companies they affect is relatively limited.

Then there are macro changes. Tech revolutions, regulatory changes and societal movements are examples. Here, an entire system can change, shifting the playing field for everyone. These shifts often come with second- and third-order knock-on effects that are extremely hard to predict but can have an even greater impact on the system and its participants. The companies on the right side of such change can become true outliers – iconic.

Major system changes of the 20th and 21st centuries include:

- Electrification (1880s-1930s)

- Automobiles (1890s-1950s)

- The post-second world war consumer boom (1945-1965)

- TV and mass media (1950s-1980s)

- Personal computers and networked information (1970s to present)

- Mobile and cloud computing (2007 to present)

The investment implications have been broad and extreme, as the S&P 500 index’s biggest companies of the past illustrate: from oil, tobacco and banks to semiconductors and platforms, the S&P 500’s top five now belong to tech.

The five largest S&P 500 companies over time:

In 1980, the top 5 companies were (largest first): IBM, Exxon, General Electric, Philip Morris and General Motors. In 2025, it's NVIDIA, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon and Meta.

Source: Goldman Sachs, American Enterprise Institute. As of 31 August 2025.

If it’s outliers you seek, system change is fertile ground.

So, we study systems too.

3. Conviction, laws, principles

As investors, we ultimately try to make predictions about the future. That’s hard enough as it is. But if you base those predictions on the wrong mental models or logic, you can quickly get lost.

Picture this: an apple falls from a tree – that’s a change! – and we’re asked, why? I can imagine dozens of reasons:

- The stem was weak

- The wind shook the branch

- It was ripe

- A squirrel nudged it

All of these are true, in a way. But they are incomplete – maybe contingent is a better word. They describe what happened, not why. The better answer for why the apple fell from the tree is: gravity.

Understanding gravity – the first principle – enhances our predictive power. It helps us explain not just this apple, but any falling object. It is a portable truth. A transferable insight.

First-principles thinking strips away layers of noise. It asks: what are the fundamental forces at play? What is universally true, regardless of context?

In business, strategy, science and investing, starting from first principles protects us from being misled by surface patterns, rules of thumb and anecdotes. It’s the difference between seeing through a problem and just staring at it.

So we also study first principles – laws and portable truths we can believe in.

Entropy and systems

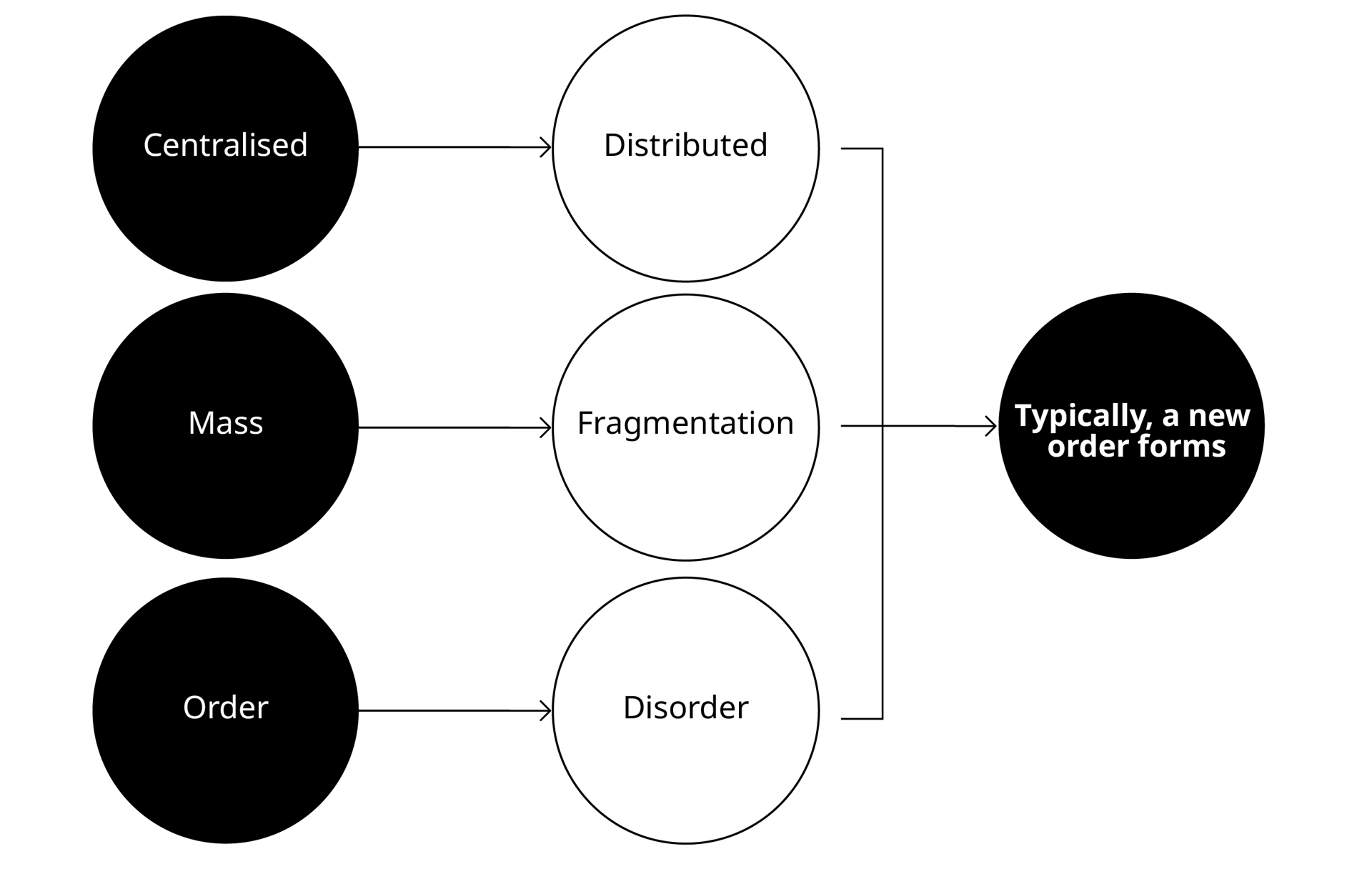

This brings us to entropy. The concept, of course, was originally tied to the study of heat, and specifically the tendency of energy to spread out and become less concentrated over time. But, as I’ve already alluded to, entropy’s role extends beyond thermodynamics to measure disorder in systems. It’s a portable truth.

Over time, systems naturally tend towards higher entropy: more randomness, more unpredictability, more options. When this happens, structures that once seemed stable begin to fragment or reconfigure.

Entropy and growth investing

I was in a meeting with Cloudflare’s chief executive, Matthew Prince, a few years ago, where he laid out his vision of how network architecture would change over the coming decades. He used the evolution of search engines to make his point.

Prince reminded us that AltaVista was the leading search engine before Google emerged. Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) developed the service and housed it on its servers. As DEC was first and foremost a hardware company, AltaVista was essentially a showcase for the power of DEC’s AlphaServer systems. Google, on the other hand, launched a search engine built on a completely different architecture.

Instead of running it on centralised machines, it used a distributed network of commodity servers and – through the magic of some very clever software – found a way to route traffic through them which, in aggregate, turned out to be far more powerful.

Maybe a physicist wouldn’t call this entropy in the purest sense of the word, but it’s an example of how systems tend to move in time from centralised to distributed.

Indeed, in the past few decades, we’ve all experienced this dynamic across so many aspects of our lives. Information systems are the most obvious example: the internet massively increased entropy by lowering the cost of publishing and distributing information. This led to the decline of most newspapers and the rise of platforms like Google and Twitter.

Media systems followed a similar path. Once dominated by a few gatekeepers, they’ve fractured into countless voices, channels and business models.

When entropy rises, incumbents often lose control, and entirely new categories of winners emerge. In retrospect, the investment implications of these system-wide changes are clear. The distribution and fragmentation of the nodes in the system shifted value away from the centralised nodes that controlled the supply (from big box retailers to major media networks to encyclopedias) to the intermediaries who could effectively aggregate the fragmented supply as well as consumer demand: Apple, Amazon, Google, Netflix, Facebook, etc.

Monumental disruption. Monumental winners.

Seeking system change: American culture

Last year, I read The Scientist, a book about the life of Edward O Wilson – a world-renowned biologist and naturalist, sometimes referred to as Darwin’s heir.

Wilson’s claim to fame was studying ants. Yes, ants. He embarked on the work about the same time Watson and Crick discovered the double helix, and ‘everyone’ in science rushed into genomics. Instead, Wilson pivoted towards insects. He did so because he thought the best way to generate an insight might be to look where no one else was.

My point: as someone who has studied tech for more than 20 years, I’m guilty of this too. But it seems common for folks to associate ‘disruption’ with ‘technology’ and those monumental winners I mentioned in the last section.

However, as the investment world increasingly focuses on AI and tech, perhaps it’s worth exploring change inside other systems less studied by techy growth investors. How about culture? Is it changing?

To help answer this question, we’ve developed a relationship with anthropologist Grant McCracken. Is culture being disrupted too? The short answer is yes. And the similarities with tech’s disruption are striking.

Grant McCracken: a brief bio

The Canadian-born cultural anthropologist earned his PhD at the University of Chicago and specialises in the study of deep meanings in cultural trends and consumer behaviours.

In the early 1990s, he founded and ran the Institute of Contemporary Culture at the Royal Ontario Museum and was later associated with Harvard University and MIT.

McCracken has authored 14 books, including Chief Culture Officer and Return of the Artisan.

His other consultancy clients include Alphabet, Ford, Microsoft, Netflix, Nike, and Sony.

After the second world war, new trends looked like those beautiful rollers that come running into the beach at Waikiki. Simple, clear, few. Today, culture looks more like the North Sea, filled with towering waves that collide, zero out and start again, driven relentlessly by a chaos of cross currents. There’s precious little order here.

- Grant McCracken

Waikiki v the North Sea: changes in culture

Grant’s overarching lens is what he calls the North Sea Culture. His point: US culture has changed. It is no longer orderly, linear and predictable like the ‘rolling waves’ so loved by surfers at Hawaii’s Waikiki Beach. Rather, it’s chaotic, unpredictable and disorderly, like the North Sea. That is, the pace and potency of the disruptions we observe in ‘tech’ are also happening in culture.

The implication is fragmentation.

The evidence of fragmentation may seem obvious to anyone living in US culture, but its breadth is striking (use the arrow to explore the interactive graphic below):

Then and now: how the US has changed since the 1950s

- Media: During the 1950-70s, the ‘big three’ TV networks (ABC, CBS, NBC) collectively drew more than 95 per cent of prime-time viewers. By 1994, the ‘big four’s’ (Fox included) share fell to 43 per cent. By 2009, it had plummeted to just 27 per cent. Even formerly unifying broadcasts like the Oscars have seen their live TV audiences shrink by more than 80 per cent from peak levels.

- Religion: In 1972, 90 per cent of US adults identified as Christian and just 5 per cent said they had ‘no religion’. Fifty years later, only about 64 per cent of Americans still identify as Christian, while the religious 'nones' have nearly quadrupled to 29 per cent of the population.

- Family structures: In 1960, only about 5 per cent of US births were to unmarried mothers. By the late 2010s, about 40 per cent of births occurred outside of marriage.

- Gender norms: Women’s labour force participation was about 37 per cent in 1960, but climbed steadily, peaking at nearly 80 per cent just before the pandemic.

- Working life: Long-term employment is no longer the norm. One proxy, union membership, peaked in the 1950s at nearly 35 per cent of the US workforce but by 2022 had fallen to just 10 per cent.

- Fashion: The early 1960s were marked by a singular mainstream style: men in hats and grey flannel suits, women in dresses. Even countercultures like the 1960s hippies had a definable uniform that eventually permeated popular style. This has given way to an extremely wide range of accepted apparel and hyper-personalisation.

Entropy and feedback loops

US culture seems to be experiencing a similar entropic transformation to information and media systems. Interestingly, there seems to be a common root cause: the dissolving of feedback loops that held the old order in place.

In culture’s case, the traditional centralised feedback loops – mediated by legacy institutions and mass media – have broken down. In mid-20th-century America, feedback loops reinforced cultural coherence:

- A few TV networks broadcast a common set of news and entertainment, which most people discussed in common forums.

- A few institutional authorities – including churches, schools, government and print media – disseminated norms, which were then reflected in community life and fed back into those institutions.

Essentially, information and influence flowed through a narrow set of channels, creating a self-reinforcing cultural centre. Technology, then, radically decentralised information flows and undermined those old loops. Now, instead of one town square or a few networks, we have thousands of micro-communities and channels.

Among other things, the key point in looking at culture (and these other systems) through an entropic lens is that this fragmentation is systemic, not random happenstance.

In physics, entropy increases as systems lose constraints. Analogously, US culture has shed many of the constraints or unifying forces that previously held it in a more ordered state. It will be very difficult to reverse this trend. Just as it’s hard to decrease entropy in a closed system without adding energy from outside, attempts to ‘recentre’ US culture will struggle against the powerful tide of pluralism and individualism that defines the North Sea’s high-entropy state.

Amid the chaos: trends and constellations

It’s important to acknowledge that even in a high-entropy system, patterns of behaviour form some coherence. Constellations, if you will. Sometimes these even emerge because of the fragmentation and deconstruction of the prior system.

We’ve seen this happen in the technology landscape. As the old system gave way to higher entropy, it fell apart, and a new system – a new order – replaced it, taking the form of powerful new platforms and infrastructures. Amazon, Google (now Alphabet) and Netflix are three examples.

New constellations exert cultural gravity. They pull in products, influencers, rituals, brands, aesthetics and communities. The stronger the constellation, the more people enter its orbit. As these habits change, there are investment implications.

Three current constellations

1. Decline of wellness:

The wellness movement was once a unifying cultural force centred on optimisation, purity and self-care. After decades of dominance, it’s fragmenting and giving way to a mix of emotional realism, rugged self-discipline, anti-wellness rebellion and low-effort comfort.

Gen Z – for one – seems to emphasise mental health over aesthetics, while others seek strength through adversity or reject wellness orthodoxy altogether. Saturation, elitism and scepticism have eroded trust in traditional wellness narratives.

What’s emerging is not a single replacement but a set of diverging paths. Each reflects a deeper cultural shift away from perfection and towards authenticity, resilience or survival. Wellness isn’t ending, but entropy is breaking its old form down.

2. Humanisation of pets:

This constellation is admittedly well-developed but remains powerful. You can even argue that entropy has strengthened the ‘companion animal’ constellation, unlike many other trends that took shape over the past couple of decades.

The idea: as traditional sources of connection, ritual and identity – eg religion, marriage, extended family, community institutions – have fragmented or weakened, pet relationships have taken on a bigger role. They provide owners coherence, softness, care and a shared cultural language, even if nothing else in their lives feels ordered.

3. Rise of Donald Trump:

What 2025 paper describing US culture would be complete without a mention of Donald Trump? Looking through this ‘cultural’ and ‘entropic’ lens, we focus less on things like

geopolitics and trade wars and more on the rise of Trump himself. What’s behind it?

Have entropy and the North Sea played a role?

The short answer is: yes. Rising disorder, fragmentation and breakdowns in institutional feedback loops have created the conditions in which his political ascent became not only possible but, in some ways, structurally predictable.

As with other systems, the wearing away of feedback loops opened the door:

- The erosion of national consensus in media, values and identity.

- The declining trust in institutions, including government, press, science and academia.

- The fragmentation of communities into algorithmic niches and tribal microcultures.

- The weakening of stabilising narratives, including the American Dream, meritocracy and shared moral frameworks.

Trump seems to thrive on this type of disorder and sometimes instigates it.

Investing in a North Sea culture

Let’s recap. Entropy and its effect on US culture represent change. Moreover, this is a system-wide change. There will be investment implications. Certain types of companies and brands are better positioned than others for this North Sea world.

The following are some of the implications and how they affect our portfolio companies.

Agility as an edge:

Agility illuminates the importance of corporate culture and a business’s ability to adapt and provides a genuine competitive advantage. It is especially important in founder-led companies, where the founder often has more control to pivot and move the business in a certain direction quickly. Founders lead 11 of our top 15 holdings.

But we are now in these times where there are multiple tidal waves coming from all directions, new technologies emerging here, new ideas everywhere. And we kind of have to take it from zero budget and reinvent the company over and over. And that is not possible unless you have a founder that is still active within the company.

- Tobi Lütke, co-founder and chief executive of Shopify

The new pipes:

When systems change, those with the most influence and ability to cause outsized effects change, too. This has given way to platforms that shape how norms are discovered, distributed and amplified. Meta, with its ability to reach four billion people on its platform, seems particularly well-positioned in a North Sea culture.

Platforms:

The high-entropy state makes certain business models even more valuable than they’d otherwise be. Platforms including Amazon, Shopify, Netflix, Roblox and Pinterest can remain robust and resilient while the content that sits on top is frenetic and turbulent.

Roblox, in particular, excites me. Because users create its gaming content, the product is a mirror of contemporary culture. Who could have imagined three years ago that a game that asks users to grow a garden would not just be popular but the most popular game of all time? But its creator – in this case, a 16-year-old Roblox user! – has clearly tapped into a cultural vein that involves identity, digital self-expression, creativity and perhaps even the human affinity for growth, care and nature.

Cultural anchors:

The North Sea makes cultural mainstays more valuable. In a fragmenting world, there is even greater value in that which is protected. Sport is an example. Social media and the fragmenting of attention are splintering the entertainment world. But sport is one area where people still watch together, live. There is great value in that scarcity. Online sports betting platforms, including DraftKings, have a tailwind at their back in the North Sea culture.

Authentic brands:

When it comes to brand management, yesterday’s tactics won’t work. See AB InBev’s disastrous 2023 Dylan Mulvaney ad campaign that triggered a mass boycott among the Bud Light faithful. Nike is similarly struggling in a world where ‘mass’ doesn’t guarantee success.

Brands must be authentic, appeal to subcultures and be community-focused. Sweetgreen’s support of local farmers and partnerships with regional suppliers is a case in point. Ditto for YETI’s engagement with communities as its primary go-to-market effort.

Fragmentation as white space:

The Waikiki notion of culture suggests relative homogeneity. The North Sea is more

heterogeneous. With that shift comes more white space and fragments for an innovative company to address.

SharkNinja does just that. It makes home appliances, from vacuum cleaners to air fryers. But unlike rivals whose entire brand caters to one category (eg Vitamix’s blenders or SodaStream’s drink carbonators), SharkNinja operates across dozens of categories. Said another way, it serves the fragments to seed new addressable markets. One impressive example involves its creation of an ice-cream maker. When SharkNinja entered the category, the entire total addressable market was only $50m. It’s now well above a $150m business for SharkNinja alone.

Antidotes for entropy:

Samsara is an Internet of Things company that helps businesses monitor their vehicles and other physical assets’ performance, condition and location. While Samsara itself doesn’t represent a move towards higher entropy, it sits at an interesting point between entropy and order in its system. Here, supply chains are becoming more fragmented and less predictable, labour is more fluid, regulatory complexity has grown and assets are more distributed (from decentralised fleets to mobile workforces).

This means the feedback loops that once maintained order – eg tight managerial oversight, physical paperwork and co-located teams – are loosening. The system is more complex, volatile and hard to see in real time. In other words, more entropic. Samsara is using digital technology to help its clients manage the disorder.

The next systems to tip:

It’s worth emphasising that the end state for these systems isn’t disorder. Yes, entropy helps tear down the old system, but ultimately, a new order will form. Perhaps the biggest or at least broadest investment implications will involve identifying entire systems in the early stages of experiencing entropic pressure that will ultimately give way to a new order.

What are the feedback loops that have kept the old order in place? Are they beginning to fray? If it fragments, what businesses will be on the right side of change? Two that come to mind and beg more study through this framing are the financial system and energy production.

There are signs of entropy for both. In one case, the popularity of and recent administrative/regulatory support for cryptocurrency, DeFi (decentralised finance) and growing interest around stablecoins.

In the other, the strains on the centralised grid and the emergence of distributed energy production, from solar panels to forthcoming modular nuclear reactors.

In both systems, the feedback loops are strong, so the shift to a high-entropy state is far from certain. But given the implications when systems this large change, both systems

beg a deeper study through the lens we have walked through today. With regard to crypto, we participated in Circle Internet’s 2025 IPO.

The innovators:

A final note: don’t conflate cultural entropy with chaos or anarchy in a purely negative sense. Higher disorder in culture can also mean higher creativity and diversity – a system with many different parts interacting in novel ways. A type of creative, transformational synthesis.

We can see this in Duolingo, Tempus and Oddity using AI to transform education, healthcare and beauty and wellness, respectively. It’s evidenced by Sweetgreen bringing automation to food preparation and Aurora’s fleet of self-driving trucks.

Conclusion

In a high-entropy world, investors will receive outsized returns if they back the builders who are harnessing the chaos, riding the stormy seas and using the disorder to their advantage to define what comes next for the system and for our future.

Entropy reminds us that change is not the exception but the rule. Disorder may feel uncomfortable, but it is precisely in those moments of fragmentation that the greatest opportunities for reinvention emerge.

By embracing that truth with clarity and courage, we will not only survive the turbulence but also have a better chance of spotting the outliers that will define the future.

Risk Factors

The views expressed should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. They reflect opinion and should not be taken as statements of fact nor should any reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

This communication was produced and approved in October 2025 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of writing and may not reflect current thinking.

This communication contains information on investments which does not constitute independent research. Accordingly, it is not subject to the protections afforded to independent research, but is classified as advertising under Art 68 of the Financial Services Act (‘FinSA’) and Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned.

All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co and is current unless otherwise stated.

The images used in this communication are for illustrative purposes only.

Important Information

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is an Authorised Corporate Director of OEICs.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides investment management and advisory services to non-UK Professional/Institutional clients only. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited are authorised and regulated by the FCA in the UK.

Persons resident or domiciled outside the UK should consult with their professional advisers as to whether they require any governmental or other consents in order to enable them to invest, and with their tax advisers for advice relevant to their own particular circumstances.

Financial Intermediaries

This communication is suitable for use of financial intermediaries. Financial intermediaries are solely responsible for any further distribution and Baillie Gifford takes no responsibility for the reliance on this document by any other person who did not receive this document directly from Baillie Gifford.

Europe

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Ltd (BGE) is authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland as an AIFM under the AIFM Regulations and as a UCITS management company under the UCITS Regulation. BGE also has regulatory permissions to perform Individual Portfolio Management activities. BGE provides investment management and advisory services to European (excluding UK) segregated clients. BGE has been appointed as UCITS management company to the following UCITS umbrella company; Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc. BGE is a wholly owned subsidiary of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, which is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and Baillie Gifford & Co are authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority.

China

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Shanghai) Limited 柏基投资管理(上海)有限公司(‘BGIMS’) is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and previously provided investment research to the Baillie Gifford Group pursuant to applicable laws. BGIMS is incorporated in Shanghai in the People’s Republic of China (‘PRC’) as a wholly foreign-owned limited liability company with a unified social credit code of 91310000MA1FL6KQ30.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Investment Fund Management (Shanghai) Limited柏基海外投资基金管理(上海)有限公司(‘BGQS’) is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. BGQS is incorporated in Shanghai as a limited liability company with its unified social credit code of 91310000MA1FL7JFXQ. BGQS is a registered Private Fund Manager with AMAC with a registration code of P1071708. BGQS has been approved by Shanghai Municipal Financial Regulatory Bureau for the Qualified Domestic Limited Partners (QDLP) Pilot Program, under which it may raise funds from PRC investors for making overseas investments.

Hong Kong

Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and holds a Type 1 license from the Securities & Futures Commission of Hong Kong to market and distribute Baillie Gifford’s range of collective investment schemes to professional investors in Hong Kong. Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited

柏基亞洲香港有限公司 can be contacted at Suites 2713-2715, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong. Telephone +852 3756 5700.

South Korea

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is licensed with the Financial Services Commission in South Korea as a cross border Discretionary Investment Manager and Non-discretionary Investment Adviser.

Japan

Mitsubishi UFJ Baillie Gifford Asset Management Limited (‘MUBGAM’) is a joint venture company between Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Banking Corporation and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. MUBGAM is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Australia

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited (ARBN 118 567 178) is registered as a foreign company under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and holds Foreign Australian Financial Services Licence No 528911. This material is provided to you on the basis that you are a “wholesale client” within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (“Corporations Act”). Please advise Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited immediately if you are not a wholesale client. In no circumstances may this material be made available to a “retail client” within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act.

This material contains general information only. It does not take into account any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs.

South Africa

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered as a Foreign Financial Services Provider with the Financial Sector Conduct Authority in South Africa.

North America

Baillie Gifford International LLC is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited; it was formed in Delaware in 2005 and is registered with the SEC. It is the legal entity through which Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides client service and marketing functions in North America. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered with the SEC in the United States of America.

The Manager is not resident in Canada, its head office and principal place of business is in Edinburgh, Scotland. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is regulated in Canada as a portfolio manager and exempt market dealer with the Ontario Securities Commission ('OSC'). Its portfolio manager licence is currently passported into Alberta, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Newfoundland & Labrador whereas the exempt market dealer licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories.

Israel

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is not licensed under Israel’s Regulation of Investment Advising, Investment Marketing and Portfolio Management Law, 5755-1995 (the Advice Law) and does not carry insurance pursuant to the Advice Law. This material is only intended for those categories of Israeli residents who are qualified clients listed on the First Addendum to the Advice Law

Singapore

Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore as a holder of a capital markets services licence to conduct fund management activities for institutional investors and accredited investors in Singapore. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, as a foreign related corporation of Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited, has entered into a cross-border business arrangement with Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited, and shall be relying upon the exemption under regulation 4 of the Securities and Futures (Exemption for Cross-Border Arrangements) (Foreign Related Corporations) Regulations 2021 which enables both Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited to market the full range of segregated mandate services to institutional investors and accredited investors in Singapore.

171501 10057520

Read the next article in our latest Long view series:

Artificial intelligence: the world is about to get ‘weird’