All investment strategies have the potential for profit and loss, your or your clients’ capital may be at risk.

I took up the role of head of ESG at Baillie Gifford last year. Gavin, who sits next to me and started working in the investment industry 32 years ago, is an expert on governance. He tells me that I’m an example of ESG 2.0.

ESG (the consideration of environmental, social and governance factors) has become mainstream. The idea of it being the preserve of “sandal-wearing hippies kept in the basement” (Gavin’s phrase, not mine) is decades out of date.

Investment managers and analysts explicitly consider the topic as part of their work, and dedicated professionals have increased in number. Assets in funds claiming to be sustainable or ethical have more than doubled on a five-year view1. Asset owners are aware of the influence their capital has in the real world – on the environment, people’s living conditions and increasing prosperity – and they are more vocal about the values they expect to apply to their portfolios. “Hooray,” shout the sandal-wearing hippies, “we have won the day.”

The state of play: a great divide

If only it were that simple. ESG has become mainstream, but it now faces unprecedented scrutiny.

The ESG debate in 2022 was characterised by a split in opinion across the globe about the role that companies and other assets should or shouldn’t have in tackling social and environmental agendas. Much of this challenge has been politically motivated, but it also asks legitimate questions of an industry that exists to look after other people’s money.

Several US states have made clear that asset managers shouldn’t screen out fossil fuel companies or advance a particular environmental or social agenda. They feel some have been acting beyond their brief.

Indeed, asset managers have created some of their own problems. A string of senior people have exited their posts over the past couple of years in a series of high-profile incidents2 and, in doing so, called into question the integrity of the ESG 2.0 effort.

We have seen greenwash aplenty, involving unsubstantiated eco-friendly claims, and even the emergence of the concept of ‘greenhushing’ – failing to disclose the integration of ESG factors as part of the investment process. 2023 shows little sign of rifts healing. ESG integration now offers a very real complication for the asset management industry: we cannot be all things to all people.

A regulatory tangle

A patchwork of global regulation is emerging as rule-makers attempt to variously promote, prevent, control and clarify the proliferation of ESG claims and products:

- The well-meaning European Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) is widely thought to have become an exercise in bureaucracy. A review is already in the pipeline.

- Some regulators in Asia, who had been looking to take their lead from SFDR, have taken a stricter stance in relation to what can be considered as ESG funds.

- UK consumers suffer a ‘trust deficit’, the Financial Conduct Authority’s ESG director Sacha Sadan suggested at last year’s UN Principles of Responsible Investment conference.

- The US Securities and Exchange Commission is considering its own sustainable fund-disclosure rules, and states differ in how they define fiduciary duty (the obligation to act in clients’ best interests).

This regulatory tsunami is quite a departure for a corner of investment management that was regarded as a bit ‘fluffy’.

Yet elsewhere, regulators are curiously silent. Climate pledges have been backed up with little real action, though the US’s Inflation Reduction Act is a notable exception thanks to the hundreds of billions of dollars of tax breaks and spending it contains to fund clean energy and cut healthcare costs.

I worry about the mixed motivations and immaturity of regulation. Attempting to provide simple clarity and integrity is one thing, nudging capital flows in a particular direction is quite another. Pursuing any ideological agenda via finance without a well-established regulatory regime seems ill-fated.

Aside from the world of fund regulation, the UK has historically been a leader in corporate governance, so the direction of travel at home is interesting to watch. Yet instead of leading, the UK is trying to simultaneously remove and add red tape. Consultations are underway to relax local listing rules, mimicking the US, while the Corporate Governance Code3 and Stewardship Codes look set to expand. Rule changes identify the right problems – lack of competitiveness and innovation – but offer solutions that are misguided at best.

The prevailing wind seems to be moving away from ‘comply or explain’ and a tolerance for governance models that can be unique but must be effective, to a one-size-fits-all approach. Trust and accountability are being replaced with a web of rules. All in all, this is unlikely to lead to better-functioning markets.

Core values

Most importantly, the events of 2022 have badly fractured geopolitical stability among developed nations. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has had devastating humanitarian consequences, including thousands of deaths. Beyond Ukraine’s borders, this is clearly a fight for the core values of the west and another event that damages the relative global harmony and free trade that we have enjoyed for decades. Progress is proving messier than the idealists hoped.

Back in the world of capital markets, this led to a spike in energy prices and a rally in traditional oil and gas stocks. Their earlier weakness had reflected uncertainty about how to navigate the world after 2015’s Paris Agreement, which saw world leaders commit to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to limit global temperature rises.

The rally was a real finger in the eye for growth managers, including ourselves, who saw and still generally see long-term challenges for these companies’ business models. Were we mistaken to think that the world would inevitably wean itself off fossil fuels in favour of potentially cleaner and more secure forms of energy?

It seems that ESG is pushing capital markets to their limits. Critics say shareholders and corporates have become overburdened with the expectation of representing all stakeholders. And institutional shareholders are expected to invest in one direction while the reality of the capital markets still operates in the old, pre-Paris paradigm. In February, BP’s shares rose 8 per cent when it announced it would slow the tapering off of its fossil fuel energy production, though it has still underperformed global stock markets on a five-year view4.

This leaves me to pause and ask: where are we with ESG 2.0? Is it working? Is it over? What is our role? What do we do now? How do we think about an environment that has never been so rich with opportunity but is filled with expectation and peril?

Growing pains, not death throes

Thanks to all the above, life in the land of ESG has been difficult over the past couple of years. I hear it from peers, clients, companies and even regulators. Is ESG even a separate concept or just the pursuit of strong long-term returns? Is it over? Maybe if we explode the three initials and stop treating them as a single concept we can master it. Maybe we are already at the end of ESG.

My view is that we are experiencing growing pains, not death throes. During my career, I have seen two major shifts that I think underpin genuine change: the first social, the second environmental.

The first was the global financial crisis. As a graduate joining an investment bank in 2008, I had a front-row seat to the collapse of the banking sector and the societal anger it provoked. I was protected on my way into work by security guards keeping protesters at bay.

Against a long-term backdrop of growing inequality, we saw the beginning of differing expectations for finance and big business more generally. Scepticism that the received wisdom of the boardroom would win out was given new impetus. The ‘men in suits’ had got it wrong. The banks could not reap vast rewards for executives and shareholders with flagrant disregard for society at large since society at large had to pick up the cheque.

To win over the long run, companies need to maintain support, both in terms of the local communities their operations impact and the wider public, what’s known as a ‘social licence to operate’. And 10 years after the financial crisis, the suits at the Business Roundtable – a group of US chief executives generally seen as a barometer of the mainstream corporate world – ‘redefined’ the purpose of a corporation. They said it needs to act on behalf of all stakeholders and not merely grow earnings for shareholders.

Many have argued it was ever thus, and the period of capitalism broadly from the 1980s until 2008 was the aberration5. Regardless, the goalposts for maintaining a social licence to operate keep moving. We reflect this in our investment research: several of our largest investment strategies now incorporate explicit questions as part of their core research on society contribution and social licence to operate.

Climate change

The second shift I have witnessed is climate change. We accept scientific evidence that the planet is warming because of CO2 emissions. It seems very unlikely to us that a warming planet will be allowed to continue unchecked because of the consequences that will have on how we live, where we live and how we feed ourselves. The physical and regulatory consequences for businesses over the very long term may well be profound. The skill is in balancing that with our own, still very long, investment horizon and return expectations.

We recognise we are on course for a warmer planet, the question is how much warmer. So we’re looking at companies whose products and services can capture opportunity, from batteries to drought-resistant seed manufacturers and everything in between. We’re also factoring in where companies may face significant headwinds if they don’t move in line with the changing environment.

Last year, we engaged with CRH, which makes cement and other building materials, on its plans to operate profitably amid rising carbon taxes. Calls from some for CRH to sell off its cement business and to make it someone else’s problem seem questionable. Cement is critical to infrastructure development and not yet replaceable, so this could remain a profitable business if a major player can invest to decarbonise and run it responsibly. Not all suppliers will be so well placed.

Our focus here is on long-term value creation, being realistic about the real-world impacts of our actions and careful stewards of our clients’ capital.

Shareholder v stakeholder

Beyond recognising the changes around us, what is our role? Are we the representative of the shareholder or the stakeholder? We are very clear on our purpose as a firm: we are here to deliver returns. Our clients hired us for this purpose. Our industry exists for this purpose, and it’s core to securing financial security for those we serve. That is a social good.

We are proud that most of our business comes from the collected pensions of public and private sector workers. We are agents of our clients and stewards of their assets. We will invest in accordance with the mandates they give us.

We also recognise that, as investors, we have a responsibility. We aim to support a broader contribution to society, to invest in enterprises that add value broadly defined. We do not view these elements as being in tension but rather as complementary.

The ability to deliver good returns for shareholders while being a responsible advocate for stakeholders when it matters is an opportunity that excites us, not an imposition of which we’re fearful.

Doing what we say, saying what we do

From all this, I draw four conclusions.

Firstly, we must remain focused on opportunities for our clients and on excellent research. We have investments in transformational companies, including:

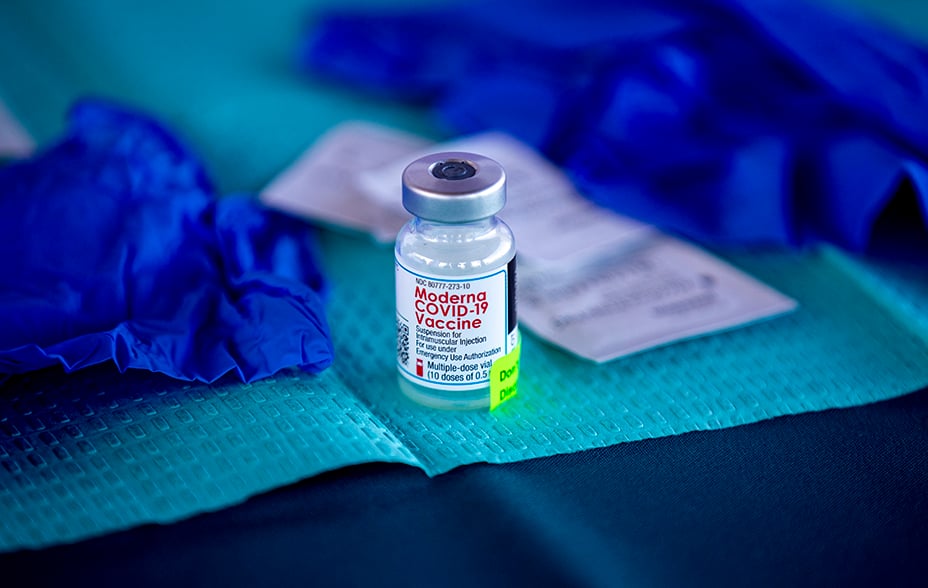

- Moderna, whose Covid vaccine has saved countless lives

- Redwood, which is trying to provide clean battery materials for the energy transition

- ASML and other semiconductor-related companies that enable innovation across a range of sectors

We also invest in mining companies that supply the minerals for the transition and other companies in heavy industry where decarbonisation will be challenging but necessary. But the direction of travel and the weight of money across our clients’ portfolios is clear.

In all cases, we aim for research that goes beyond the surface, and we’re always learning. We’re improving the sophistication of our climate models and assessing companies’ climate exposure on a bottom-up basis rather than relying on blunt exclusions based on questionable data. We are educating ourselves about topics like biodiversity and how to grapple with human rights issues in complex global supply chains.

We work hard to understand whether governance models are appropriate for delivering long-term returns. There are no shortcuts to understanding these issues, and there is no such thing as the perfect company.

Secondly, we aim for meaningful engagements with the companies we hold. As long-term active managers, we are in a fantastic position to do this well. We aim for quality, not quantity.

Where we engage on ESG-related topics, we retain a focus on long-term returns. We think that engaging with holdings to understand their social licence to operate and whether they have strategies in place concerning climate change is sensible. We have long known that robust corporate governance and an effective board underpin success.

We generally trust the companies we invest in because, as active managers, we select investments that we already think are winners. But we aim to hold those companies accountable if that trust is broken.

End results, not ticked boxes

Thirdly, we will focus on key outcomes rather than getting lost in the weeds. That means long-term returns for our clients and, in the case of impact funds, other goals such as tackling climate change or reducing social inequalities.

Where we market our products as ESG or impact-focused, we want to lead the industry in quality and transparency when demonstrating the environmental or social values those products deliver. We’re proud of our Positive Change portfolios in this regard.

ESG 2.0 is in danger of straying into a cottage industry of box-ticking and data gathering that doesn’t deliver more responsible corporate behaviour or sustainable development. Greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, though, hopefully, the groundwork is being laid for a transition. Chief executive pay relative to average worker pay has increased despite so-called ‘say on pay’ provisions that gave investors the right to vote on senior management pay at annual shareholder meetings.

We will resist the clamour for yet more information or another shiny initiative in favour of thoughtful analysis and direct conversations on what matters. We will try to demonstrate that more clearly to clients and be clearer about our priorities.

Finally, we aim to show leadership and inject some much-needed honesty into this debate. ESG 2.0 is complex and still finding its feet. We are in an industry that is overpromising and underdelivering. We know the trust deficit is real. I will be honest and say now: we cannot engage with every company in every portfolio on every matter. That would be a poor use of our time and would lead to worse results for our clients and stakeholders.

We will not impose a particular ideology on our investments. Legitimate client views are too divergent for us to do this honourably as stewards. We will not shy away from addressing climate or other controversial topics with companies where they are a material investment factor. We will be transparent and stay true to our investment beliefs.

We are not yet, as Prof Alex Edmans argues in The End of ESG, at the point where ESG is so truly integrated that it is simply part of the investment. The shifts I note above mean it still represents something subtly different and, at times, a challenge to the status quo.

ESG will become fully integrated, but there will be no end. For us, it is part of our constant bid for improvement. We feel confident in our ability to do this because it relies on the same skills of analysis and patience that we have always employed.

Change is not new to us. We’re ready for it and excited by it as active, long-term investors. There’s a huge opportunity to invest in enterprises that can solve society’s problems and succeed financially in a world of changing demands. We feel privileged to do so.

1. According to Morningstar’s Sustainable Fund Flows data, funds under management in sustainable products had risen by 118 per cent on a five-year view, as at the end of July 2023.

2. Stuart Kirk, formerly of HSBC and now back at the FT wrote (FT) headlines and his own P45 with remarks about climate change that were widely regarded as rather flippant; Tariq Fancy had already resigned from BlackRock and was happily doing the speaking circuit talking broadly about the greenwashing phenomena he had witnessed. Desiree Fixler blew the whistle on DWS, who later received a $4m fine for mis-selling. The situations and motivations of each of these individuals and their organisations were unique, but together they created an alarming pattern.

3. The Cadbury Committee's 1992 landmark UK Governance code was under 750 words long. The most recent iteration is almost five times as long. This is an observation made by the excellent Dr Bobby Reddy (introduction thanks to Gavin Grant) https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/business-law-blog/blog/2022/06/why-it-time-say-goodnight-uk-corporate-governance-code

4. Bloomberg based on 5-year cumulative total return to end June 2023 v MSCI ACWI.

5. Prof William Magnusson, For Profit: A History of Corporations and John Kay’s Other People’s Money both make this point eloquently.

Risk factors

The views expressed should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. They reflect opinion and should not be taken as statements of fact nor should any reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

This communication was produced and approved in September 2023 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of writing and may not reflect current thinking.

This communication contains information on investments which does not constitute independent research. Accordingly, it is not subject to the protections afforded to independent research, but is classified as advertising under Art 68 of the Financial Services Act (‘FinSA’) and Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned.

All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co and is current unless otherwise stated.

The images used in this communication are for illustrative purposes only.

Important information

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is an Authorised Corporate Director of OEICs.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides investment management and advisory services to non-UK Professional/Institutional clients only. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited are authorised and regulated by the FCA in the UK.

Persons resident or domiciled outside the UK should consult with their professional advisers as to whether they require any governmental or other consents in order to enable them to invest, and with their tax advisers for advice relevant to their own particular circumstances.

Financial intermediaries

This communication is suitable for use of financial intermediaries. Financial intermediaries are solely responsible for any further distribution and Baillie Gifford takes no responsibility for the reliance on this document by any other person who did not receive this document directly from Baillie Gifford.

Europe

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited provides investment management and advisory services to European (excluding UK) clients. It was incorporated in Ireland in May 2018. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited is authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland as an AIFM under the AIFM Regulations and as a UCITS management company under the UCITS Regulation. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited is also authorised in accordance with Regulation 7 of the AIFM Regulations, to provide management of portfolios of investments, including Individual Portfolio Management (‘IPM’) and Non-Core Services. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited has been appointed as UCITS management company to the following UCITS umbrella company; Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc. Through passporting it has established Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (Frankfurt Branch) to market its investment management and advisory services and distribute Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc in Germany. Similarly, it has established Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (Amsterdam Branch) to market its investment management and advisory services and distribute Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc in The Netherlands. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited also has a representative office in Zurich, Switzerland pursuant to Art. 58 of the Federal Act on Financial Institutions (‘FinIA’). The representative office is authorised by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA). The representative office does not constitute a branch and therefore does not have authority to commit Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited is a wholly owned subsidiary of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, which is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and Baillie Gifford & Co are authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority.

China

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Shanghai) Limited

柏基投资管理(上海)有限公司(‘BGIMS’) is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and may provide investment research to the Baillie Gifford Group pursuant to applicable laws. BGIMS is incorporated in Shanghai in the People’s Republic of China (‘PRC’) as a wholly foreign-owned limited liability company with a unified social credit code of 91310000MA1FL6KQ30. BGIMS is a registered Private Fund Manager with the Asset Management Association of China (‘AMAC’) and manages private security investment fund in the PRC, with a registration code of P1071226.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Investment Fund Management (Shanghai) Limited

柏基海外投资基金管理(上海)有限公司(‘BGQS’) is a wholly owned subsidiary of BGIMS incorporated in Shanghai as a limited liability company with its unified social credit code of 91310000MA1FL7JFXQ. BGQS is a registered Private Fund Manager with AMAC with a registration code of P1071708. BGQS has been approved by Shanghai Municipal Financial Regulatory Bureau for the Qualified Domestic Limited Partners (QDLP) Pilot Program, under which it may raise funds from PRC investors for making overseas investments.

Hong Kong

Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and holds a Type 1 and a Type 2 license from the Securities & Futures Commission of Hong Kong to market and distribute Baillie Gifford’s range of collective investment schemes to professional investors in Hong Kong. Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 can be contacted at Suites 2713–2715, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong. Telephone +852 3756 5700.

South Korea

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is licensed with the Financial Services Commission in South Korea as a cross border Discretionary Investment Manager and Non-discretionary Investment Adviser.

Japan

Mitsubishi UFJ Baillie Gifford Asset Management Limited (‘MUBGAM’) is a joint venture company between Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Banking Corporation and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. MUBGAM is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Australia

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited (ARBN 118 567 178) is registered as a foreign company under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and holds Foreign Australian Financial Services Licence No 528911. This material is provided to you on the basis that you are a ‘wholesale client’ within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (‘Corporations Act’). Please advise Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited immediately if you are not a wholesale client. In no circumstances may this material be made available to a ‘retail client’ within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act.

This material contains general information only. It does not take into account any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs.

South Africa

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered as a Foreign Financial Services Provider with the Financial Sector Conduct Authority in South Africa.

North America

Baillie Gifford International LLC is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited; it was formed in Delaware in 2005 and is registered with the SEC. It is the legal entity through which Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides client service and marketing functions in North America. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered with the SEC in the United States of America.

The Manager is not resident in Canada, its head office and principal place of business is in Edinburgh, Scotland. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is regulated in Canada as a portfolio manager and exempt market dealer with the Ontario Securities Commission (‘OSC’). Its portfolio manager licence is currently passported into Alberta, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Newfoundland & Labrador whereas the exempt market dealer licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories. Baillie Gifford International LLC is regulated by the OSC as an exempt market and its licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (‘BGE’) relies on the International Investment Fund Manager Exemption in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec.

Israel

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is not licensed under Israel’s Regulation of Investment Advising, Investment Marketing and Portfolio Management Law, 5755–1995 (the Advice Law) and does not carry insurance pursuant to the Advice Law. This material is only intended for those categories of Israeli residents who are qualified clients listed on the First Addendum to the Advice Law.

Ref: 58428 10035680