Prof Dame Diane Coyle’s new book examines productivity in the digital age

Photography by Liam Russell

As with any investment, your capital is at risk.

Lillian Li: In your new book, The Measure of Progress, you describe GDP [gross domestic product] as belonging to a vanished world of cornfields and steelworks. What’s convinced you that it can’t just be updated?

Diane Coyle: I wrote a book 10 years ago called GDP, A Brief but Affectionate History, and I’ve since grown less affectionate. Not only have the aspects that were missing then – such as environmental impacts and unpaid social care – grown in importance, but they’ve been joined by failure to track what’s happening in the digital economy. National agencies aren’t collecting need-to-know statistics on how supply chains are organised, how much free online content is produced, and how much data is switching between datacentres.

LL: You want statisticians to measure ‘comprehensive wealth’, covering natural, human, social and intangible capital. How might that refocus the attention of investors and policymakers?

DC: You don’t assess the health of a company just by looking at the profit and loss account. It’s the balance sheet that tells you how sustainable its activities are. It’s the same for an economy. If you’re investing, say, in food production companies, you might think differently about their future if you were aware of the degradation of soil quality or biodiversity loss that will hammer agricultural productivity in 10 years. You might think about human capital in terms of the health of the population, and how that’s related to air pollution. And with the AI revolution, it’s partly about measuring formal skills but also the capacity to work in very different ways using new technologies.

Looking at wealth in a different way

LL: What counts as comprehensive wealth?

DC: The term is intended to get people thinking about what’s needed to enable the economy to grow in ways that make people better off. That includes what we normally think of: machines and buildings and physical infrastructure. But it’s also things that are more often overlooked and certainly don’t have statistics collected about them.

‘Human capital’ is normally measured in formal educational skills but that’s quite a narrow definition. Covid demonstrated that the long-term health of the population matters. So it’s what makes you healthy, what gives you a nice environment to live in, as well as what infrastructure and machines can help conventional economic activities.

There’s a further question about how to value these concepts, some of which are quite fuzzy. Economists use ‘shadow prices’, an attempt to measure true value to society. This is getting into very philosophical territory. But progress is a philosophical concept.

LL: Where should those shadow prices come from?

DC: There are different methods you can use. One is to use something that you can observe, like house prices, to measure the benefits of being near green space and clean air.

It’s called ‘revealed preference’: people pay more for those amenities. Another is to ask people, but the tricky bit is measuring the impact of things like beetles or soil quality that people don’t like or think about but which are fundamental to the ecosystem.

For good measure: Lillian Li in conversation with Diane Coyle

Photography by Duncan Elliott

LL: You say the UN Statistical Commission’s new System of National Accounts [SNA25] represents only incremental change. What would transformative change look like?

DC: SNA25 contains a little bit about financial instruments, fintech and the environment but still gives no idea of the production structure of the modern economy. That data is not collected, and we don’t even have agreement about how we’d incorporate it into GDP.

Take something like the free apps we all have on our smartphones or tablets. There’s no agreement about how you treat that in GDP because there’s no price attached. Some of that activity gets into the figures because the people who produce apps are paid a salary and use electricity, but in terms of understanding the way that digital platforms have transformed the structure of the economy, it’s a blank canvas.

We should perhaps look at how people are using their time because time is a currency that we do pay with when we’re using free digital apps. That seems a good way of tracking how people are consuming. And then you might want to think about the value of that. But we’re not even at first base, before we get to complicated questions about how to measure it.

The importance of agreement

LL: Given the complexities of implementing a new system of national accounting, do we need to get the details worked out first? Or just get everyone roughly on the same page?

DC: Like changing the side of the road we drive on, everybody’s got to switch to agreed new measurements at the same time. There’s already concern that low-income countries, being much less digitised, have less incentive to agree to a different set of concepts and their measurement standards are weak.

But that doesn’t mean economists and statisticians shouldn’t be asking what the right concepts are and how we might collect the data.

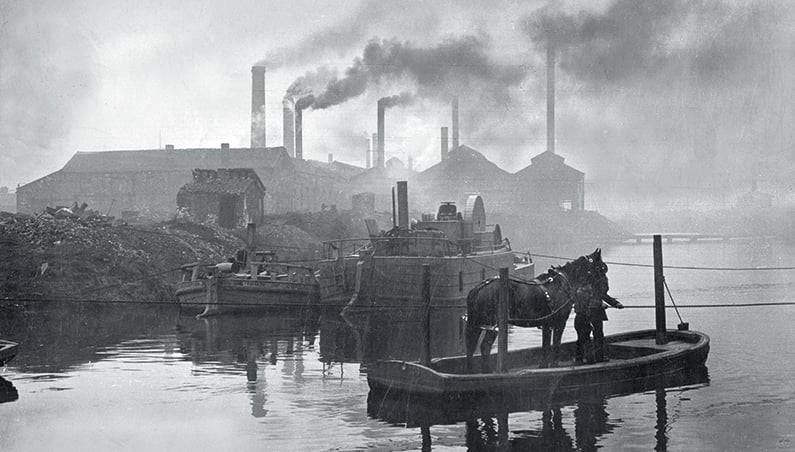

But it took 20 or 30 years to get to anything like the system of national accounts that we have now. I’ve got a yearbook of stats for 1880 that has masses of detail on arable land and livestock, when people were looking out at dark, satanic mills and Dickens was writing about inner-city slums. There’s always going to be a lag, and it’s a lot of work to switch.

Coghlan Steel Works, Leeds, circa 1900

© Bob Thomas Sports Photography/Getty Images

LL: How do we measure the social impact of transformational technology? No one quite knows what it is yet.

DC: When we introduce a new technology, that impact isn’t set in stone, it’s going to depend on many people’s choices in society. It’s about course adjustment. At least if you’re monitoring what’s really going on, you can be agile about changing direction.

LL: Some of the measurements you discuss seem very subjective and values-based. Doesn’t that make them harder to measure?

DC: People often say to me ‘why bother doing this when GDP is so objective and easy to measure?’ But of course it isn’t objective and it isn’t easy to measure. An awful lot of art goes into constructing GDP statistics. They’re highly uncertain, and the definition changes all the time.

There’s no ‘natural’ object you can measure in the way that you can measure the temperature in this room. Any set of constructs reflects values in a very fundamental way.

We’ve decided that we will classify people by race, which is a biologically arbitrary construct. We’ve decided that national boundaries are what matters, and so we measure things in national boundaries. Data isn’t objective in any way at all.

I make two arguments about why we need to rethink economic statistics. One is that GDP isn’t even satisfactory on its own terms, because it’s not measuring properly all the digital and AI-driven change. And the other is that it’s not good in the broader sense of assessing what progress is and what makes people’s lives better.

LL: What company information would most help long-term investors, such as Baillie Gifford, assess long-term value creation in this more intangible, data-driven world?

DC: AI is going to drive productivity, and AI eats data. So, the single thing that companies could do is to think about what data they have. What could they collect that they don’t? And how to use that to do the predictive analytics that will increase their profitability and, hopefully, the value they’re adding for their customers as well.

There’s quite a wide variation in how well companies are doing this already, and research now shows that the companies that do use AI predictive analytics are doing much better in terms of their profits and productivity than all the rest, and they’re pulling further and further ahead. So if you’re in the 95 per cent that’s not doing it yet, I would say, think about your end-to-end activities and which bits you should be measuring.

Important information

The views expressed in this article should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. The article contains information and opinion on investments that does not constitute independent investment research, and is therefore not subject to the protections afforded to independent research.

Some of the views expressed are not necessarily those of Baillie Gifford. Investment markets and conditions can change rapidly, therefore the views expressed should not be taken as statements of fact nor should reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Both companies are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and are based at: Calton Square, 1 Greenside Row, Edinburgh EH1 3AN.