Key points

- Global equity portfolios remain systematically underweight Emerging Markets despite these economies being home to many world-leading growth businesses

- Emerging Markets are reorganising rather than retreating from globalisation, with companies like NuBank, Kaspi and Tencent pioneering innovative business models

- Today’s Emerging Market economies are building resilience through local currency financing, deeper domestic markets and reduced western dependence

Kazakhstan and its capital, Astana, is emerging as a tech innovator driven by super app Kaspi. © Max Zolotukhin - stock.adobe.com

As with any investment, your capital is at risk

For many investors, being underweight Emerging Market (EM) equities has felt like a sensible act of caution. The headlines make it easy: political noise; currency swings; governance scandals. The scars of past crises linger, and the case for staying away almost writes itself. Yet habits formed in old cycles have persisted even as the underlying reality has changed.

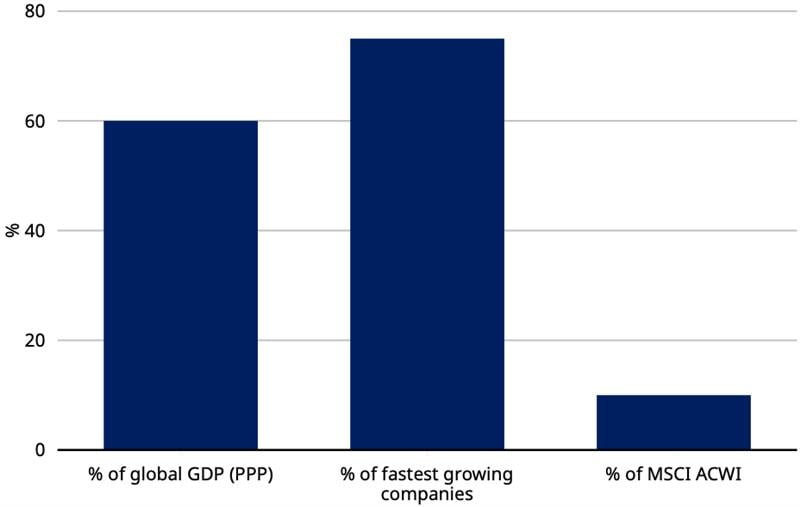

Today, many investors remain systematically underweight EM. The MSCI Emerging Markets index makes up around 10 per cent of global equity indices, yet the average global equity portfolio is roughly 3.4 per cent underweight.

At first glance, that 3 per cent underweight doesn’t sound like much. But across trillions of dollars of global assets, it adds up to a very large pool of capital. Non-US investors hold roughly $17 trillion of US equities. At the time of writing, even a modest reallocation to, say, 1 per cent would equate to more than a fifth of Brazil’s entire equity market, or just under half of Mexico’s.

In practice, that is an active bet against an ever greater share of the world's best growth companies. This disconnect matters. Thirty years of investing through EM crises and recoveries has shown us that progress across our universe accumulates quietly beneath the noise: incomes rise, fiscal prudence tends to improve, domestic capital markets deepen, and businesses of global calibre emerge.

Underappreciated and underrepresented

Source: IMF, MSCI. The second bar shows the percentage of companies in the MSCI All Country World Index with a three-year forward sales growth exceeding 20% that are based in Emerging Markets (data from 31 December 2015 to 31 December 2024).

And to that end, we ask: Emerging Markets, are you missing the point?

Not condemned to underperform

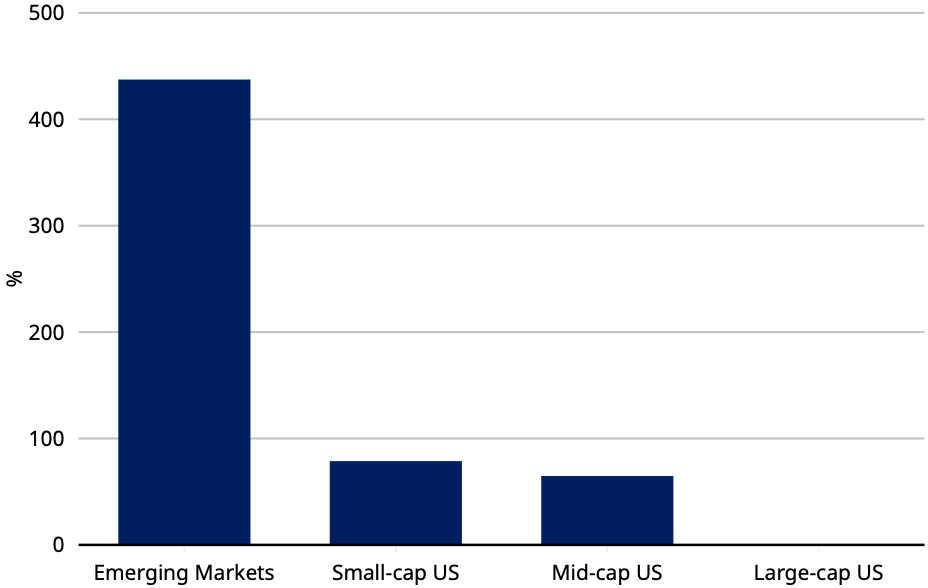

For years, investors watched EM economies expand rapidly, yet indices often lagged their developed market peers. Against the relentless rise of US technology stocks, it has been difficult to defend EM allocations. We feel your pain. But that has not always been the case. In the 2000s, EM was the clear leader: between 2001 and 2010, US large caps delivered virtually no return, while EM equities rose more than 400 per cent. Market leadership rotates, often abruptly. EM has been at the front before, and we believe the conditions are in place for it to lead again.

10-year index returns (2001-2010)

Source: Finax. 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2010. USD.

The set up today is unusually compelling. EM equities trade at one of the widest valuation discounts to developed markets in decades – around 35 per cent at the time of writing. The dollar, after years of strength, has begun to soften; historically, this makes for a more favourable backdrop for EM assets. And while sentiment on China remains fragile, domestic policy support and frontier innovation are leading to increased expectations.

And even when indices have lagged, the averages conceal the outliers. Over the past five years, Latin American ecommerce and fintech company Mercado Libre has outperformed Amazon. Taiwanese and South Korean semiconductor companies, TSMC and SK Hynix, have outperformed Alphabet and Meta.

The reality is that EMs are not condemned to underperform. At times they have been among the best performing asset classes globally. And even in challenging period, world-class EM companies have continued to deliver world-leading returns. And this year they have again been among the best performing equity markets, a reminder that sentiment can shift faster than positioning. For allocators, the greater risk is not in acting too early, but in staying underweight just as the tide begins to turn.

However, that still leaves a crucial question: is this simply another short-term rally, or the start of something more durable?

We have seen false dawns in EM before. However, we draw greater conviction today from a more supportive market backdrop that is being reinforced by structural change. Trade patterns are being reorganised, financial systems are less hostage to the dollar, and EM company ecosystems are deepening as innovation leads to new ways of doing business.

In the sections that follow, we address each of these in turn to show why the balance of risk and reward has shifted.

Re-globalisation

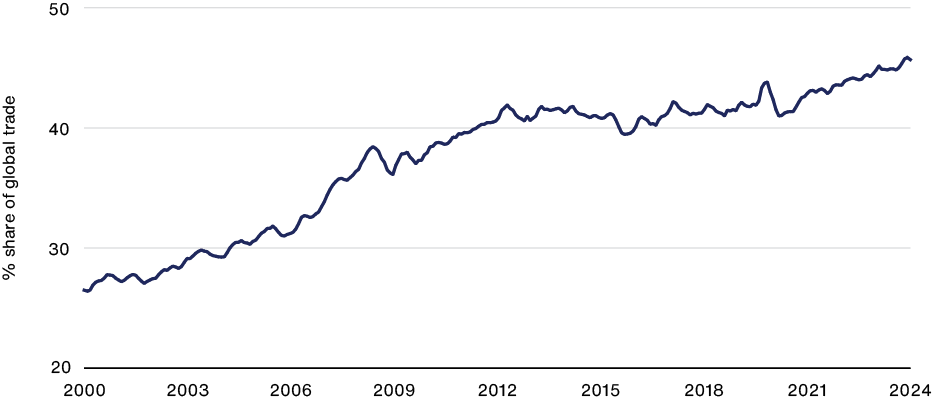

One of the most common refrains today is that we are living through deglobalisation. Supply chains are fracturing, capital is retreating, and geopolitical blocs are hardening. There is truth in that story, but it is far from the whole picture. What we are really seeing is not the end of globalisation, but its reorganisation. Supply chains are becoming more regional, more diversified, and more resilient. Companies now prize security of supply as much as efficiency, and that has drawn more of the value chain into Emerging Markets.

The numbers bear this out. Twenty years ago, only around a quarter of EM exports went to other EMs: today, it’s more than 45 per cent. Nearly half of what EMs sell is now bought by their peers. Services trade, which is harder to capture in official data, reinforces the point. India’s service exports, for example, have risen faster than goods exports and now rank among the top three globally.

Emerging markets exports are going to other EMs

Share of EM-to-EM exports in total EM exports

Source: Gavekal Research, IMF. Three-month moving average.

China is the single biggest driver of this shift, becoming the top trading partner for more than 120 countries. But this is not just a “China story”. Brazil is now one of Africa's largest protein suppliers, Korean companies are building factories in Vietnam, the UAE has pledged to invest $100bn in Indian infrastructure.

Regional corridors are being built across Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa, linking EMs directly to one another and to global markets. The proposed Capricorn Bioceanic Corridor, for example, will connect Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, and Chile from the Atlantic to the Pacific, cutting freight costs by up to 40 per cent and shortening shipping times to Asia by two weeks. These are projects that, if realised, could change competitiveness on the ground.

South-South linkages are far more robust than they were a decade ago, and they are giving EM companies growth pathways that do not rely solely on western demand.

Just as importantly, globalisation today is cultural and digital as much as it is about containers and cargo. Walk down a London high street and you will find Taiwanese bubble tea alongside Starbucks. Switch on the radio and K-pop is in the charts. Open your phone and TikTok is shaping global media habits. What once looked like curiosities from the periphery are now part of everyday life in developed markets.

Of course, geopolitics and tariffs will continue to make headlines. However, average effective US tariffs on EM exports, which remain around 18 per cent (at the time of writing), are hardly enough to offset a labour cost advantage that is still up to sevenfold in certain EMs.

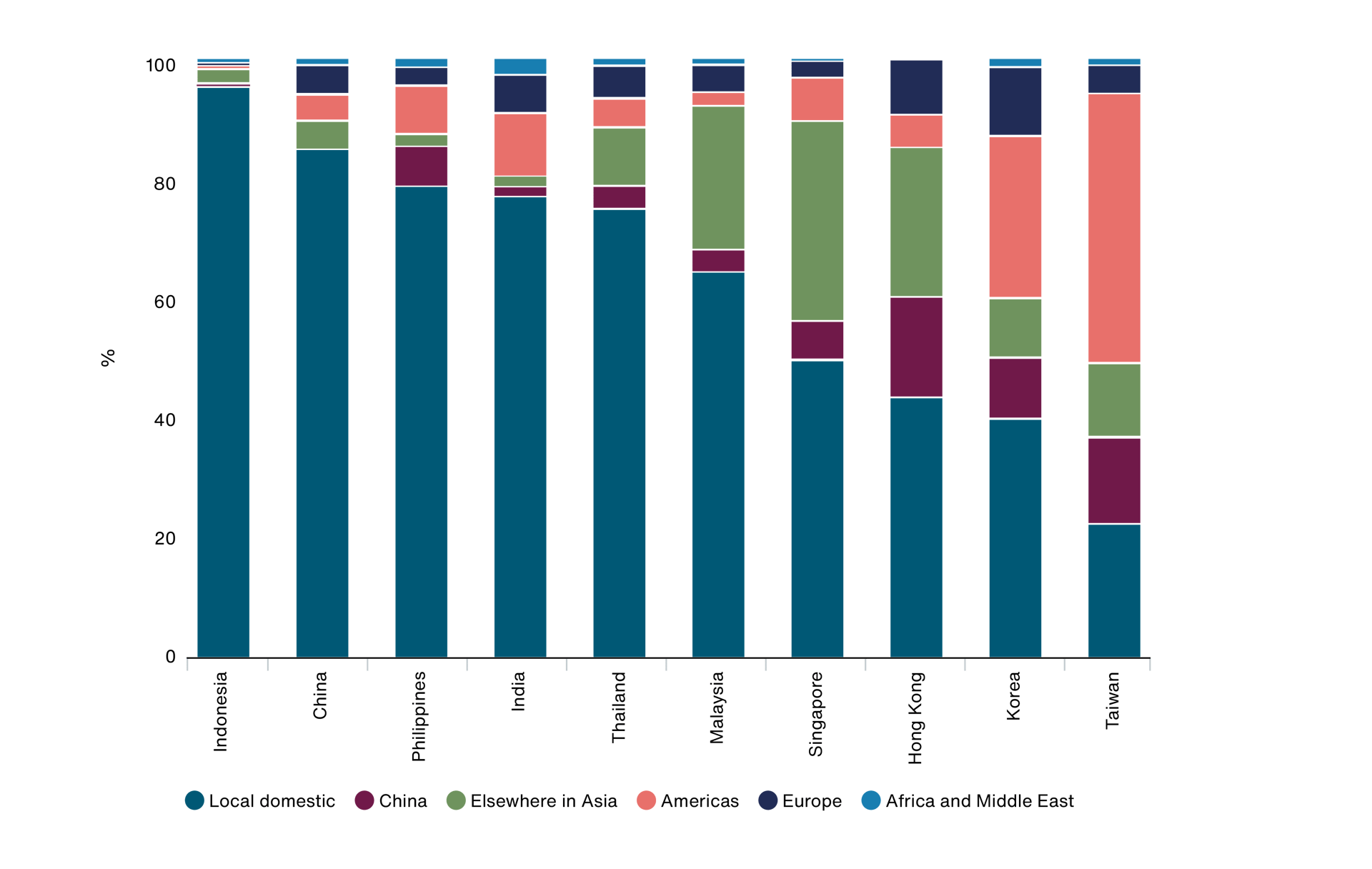

And in many cases, the tariff debate is a distraction. For EM companies, the real growth opportunity is often domestic. China’s retail market is worth $6-7 trillion a year, more than ten times the value of its exports to the US. In markets like India and Indonesia, 70-80 per cent of company revenues are generated locally. That makes EM earnings growth far less dependent on developed market demand than many investors assume.

Most emerging markets are oriented towards their domestic economies

Geographic revenue exposure

Source: FactSet, MSCI, J.P.Morgan Asset Management. Geographic revenue exposure of MSCI indices. As at 30 June 2025.

Emerging resilience

For decades, the dollar cycle defined the fate of Emerging Markets. They raised debt in dollars, hoarded reserves in dollars, and settled trade in dollars. When the dollar strengthened, capital flowed out, financing tightened, and growth faltered. However, as trade between intra-EM trade has expanded, more of it is being invoiced and settled in local currencies: whether Brazil and Argentina using swap lines for agricultural trade, or India paying for oil from the UAE in rupees. Take energy, for example, roughly a fifth of global oil trade is now settled outside the dollar. That’s a reality that was hard to imagine a decade ago.

Furthermore, though the dollar still dominates, its share of global FX reserves has been edging down for two decades. The dollar’s share of global FX reserves has fallen from over 70 per cent in 2000 to under 58 per cent today. And, according to the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, it could drop to around 52 per cent by 2035. We do not believe the dollar is disappearing, nor do we subscribe to its “demise” (despite how it conveniently fits the EM narrative). But we do see a financial system that is gradually becoming more multipolar, with a patchwork of local currencies offering greater optionality and resilience for many of our markets.

This increased resilience is visible in government financing too. Two decades ago, EM governments had little choice but to borrow in dollars. Today, the majority of sovereign debt (around 80 per cent) is issued in local currency, supported by deeper domestic markets and more credible central banks. Where once the IMF was the only backstop, many EMs now have their own buffers: higher reserves, more orthodox monetary policy, and, in some cases, legal caps on deficits.

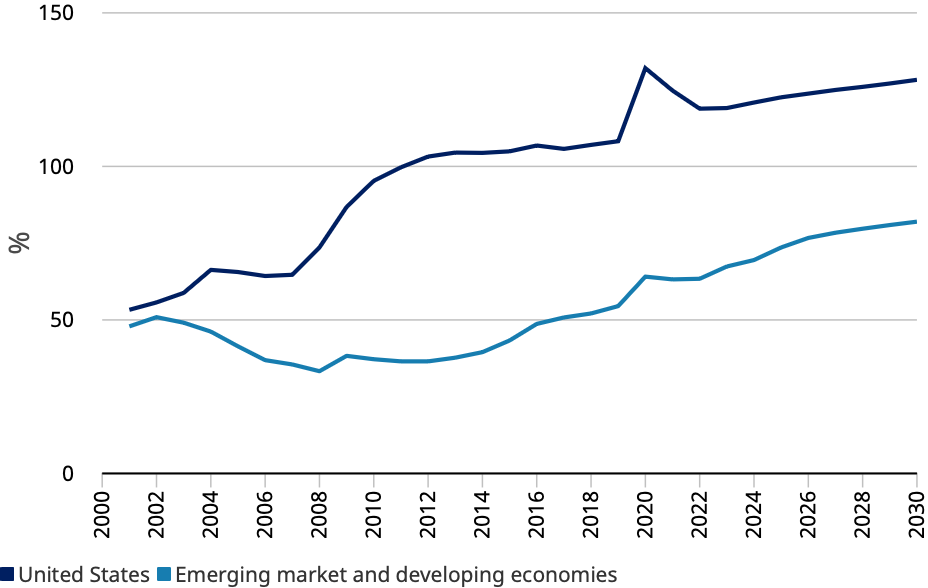

Debt profiles tell an equally important story. For years, EMs carried the reputation for unsustainable borrowing. Yet today, US government debt has risen above 120 per cent of GDP, with Europe and Japan not far behind, while EM averages sit closer to half that level. We recognise this is uncomfortable for many investors to hear, but it highlights a broader point: the vulnerabilities once associated almost exclusively with EMs are no longer theirs alone.

Emerging Markets versus US debt

General government gross debt (% of GDP)

Source: IMF. 2001 to 2025. Projections thereafter.

Of course, this does not make EMs immune to shocks. A stronger dollar still hurts, capital flows remain volatile, and political missteps can quickly undermine credibility. But an adjustment should be made: EMs are no longer wholly hostage to the dollar cycle. There is now a spectrum of vulnerability, and in many cases, it looks very different than it did 10 or 20 years ago. None of this makes EMs “safe”, but it does mean the old narrative of fragility is out of date. The risks are now more nuanced than in the past.

DMs lean on EMs

The macro picture is better than commonly portrayed: supply chains are sticky, trade is diversifying within EMs, and domestic markets are doing more of the heavy lifting. None of that means EM is “safe”. Politics can change the rules, governance isn’t always minority-friendly, currencies can swing and liquidity can be patchy. Precisely because of this, we advocate an active approach: focus on aligned management teams, defensible moats, and a blended top-down / bottom-up process that prices risk rather than avoids it.

Stepping back, we see a larger hazard running through many portfolios: concentration risk. Global equities have become increasingly top-heavy. As noted at the outset, EM is roughly 10% of the world index, while a very small group of US stocks now accounts for more than double that. At the index level, Nvidia at times rivals the entire weight of China. That imbalance is not a neutral stance; it is an active bet on a narrow set of business models, geographies and supply lines.

Here’s the blunt reality: many of today’s Developed Market (DM) champions could not exist at their current scale, or economics, without EM capacity. The AI hyperscalers are the clearest example. We can debate whether cumulative capex lands at $4tn or $6tn between now and 2030, and whether it arrives sooner or later. However, what’s harder to dispute is the dependency chain. Without EM capacity, Meta isn’t building a datacentre the size of Manhattan in Louisiana, OpenAI can’t train or serve frontier models, and Nvidia’s growth looks very different. The leading edge semiconductor manufacturing is in Taiwan; the High Bandwidth memory leadership sits in Korea; the servers, optics and networking are produced at global scale across Taiwan, China and Southeast Asia.

The same interdependence underpins both the AI build-out and the energy transition. The west can pledge trillions, but projects do not pass the planning stage without EM supply chains. Copper from Chile and Peru, nickel from Indonesia, rare earths mined and refined across Asia are the upstream bottlenecks that turn ambitions into assets. If you don’t own EM, you’re systematically underexposed to the inputs that power the platforms you already own.

A thoughtful, active EM allocation can reduce portfolio-level fragility by diversifying away from a narrow DM leadership cohort while owning the very capacity and commodities those leaders depend on.

Innovators, not imitators

For years, investors described EM companies in shorthand: “the Amazon of Latin America”, “the Uber of Southeast Asia”. The implication was that they were copycats, not innovators, destined to follow rather than lead.

However, the reality is very different. Across our universe we see companies not just competing with global peers, but often moving faster, finding cheaper and more scalable ways to serve their markets. NuBank in Brazil is one such example. It hasn’t replicated a western branch-based bank. Instead, it has built a digital platform from scratch, serving previously unbanked customers at a fraction of the cost of incumbents. Today, it has over 100 million clients, making it one of the fastest-growing financial institutions in the world.

Then there is Kaspi in Kazakhstan. Its super-app is used by nearly 80 per cent of the population for everything from booking travel to paying for a doctor. Its payments platform alone processes volumes equivalent to nearly a third of the country’s GDP. In practice, one company has taken an entire nation close to cashless.

What ties these examples together is not imitation but originality. These businesses are designed for their own markets, built around local consumers, and able to scale in ways global incumbents often cannot. And increasingly it is western peers who are the imitators: TikTok’s short-form video copied by YouTube, Pinduoduo’s group-buying model inspiring Instagram Shops.

And here China deserves particular attention. The property overhang will likely weigh for years, demographics are less favourable, and the role of the state remains unpredictable. Yet those challenges have not halted progress. China embraced ecommerce and mobile payments earlier than most, and today it is doing the same in electric vehicles (EVs), automation, and AI. EVs now account for more than half of new car sales, making China both the largest EV market and the world’s biggest car exporter.

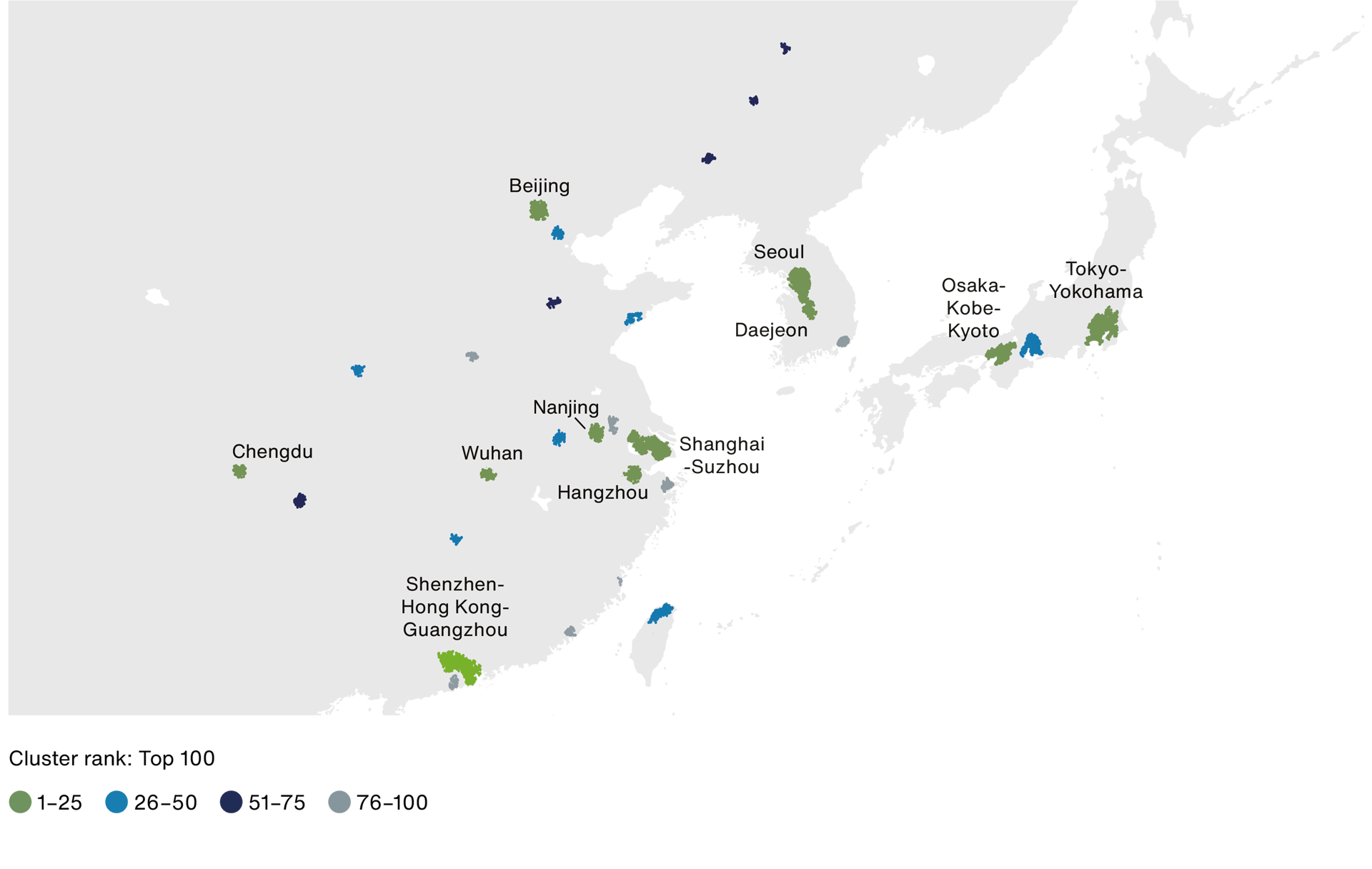

Just as important, it has built the ecosystems to keep innovating. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) ranks half of the world’s top twenty science and technology clusters in Emerging Markets, with China alone home to 26 of the top 100 – more than the US. What is striking is that many of these clusters are in so-called “second tier” cities such as Hangzhou and Nanjing, places that barely registered with global investors a decade ago but are now hubs for EVs, semiconductors, digital platforms, and healthcare.

Tech clusters matter because they concentrate talent, capital, and supply chains in one place, creating feedback loops where ideas move quickly from research to commercialisation and where companies can scale far faster than in isolation.

On the ground, the pace of adoption is striking. Across China, factories house 1.76 million industrial robots which is more than the US and Europe combined. With 1.3 billion monthly active users, Tencent is threading AI through the WeChat ecosystem, from developing a genuinely useful AI agent inside China’s most ubiquitous app to sharpening ad targeting, which is a key driver of its steadily rising advertising revenues. These are individual examples, but they highlight how quickly China can move from concept to deployment at scale.

The eastern hemisphere drives global innovation

Top global innovation clusters, according to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)

Source: WIPO Global Innovation Index, 2025.

And it is not just China. South Korea features among the WIPO’s top five technology clusters, India now has four, and Turkey, Malaysia, and Egypt entered the top 100 for the first time this year. Innovation is no longer confined to Silicon Valley or Cambridge: it is increasingly embedded in Emerging Markets, where companies are scaling on their own terms and in their own markets.

Conclusion

Over three decades of investing in Emerging Markets, we have witnessed profound transformation. EMs have become home to companies that dominate global supply chains, leapfrog ‘traditional’ ways of consumption, and apply technologies like AI at a scale that rivals, and in some cases surpasses, western peers.

As noted at the outset, global equity portfolios remain systematically underweight EM, on average by more than three percentage points. That is not a neutral stance. It is an active bet that the next generation of growth and innovation will remain confined to a narrow set of developed market companies, that globalisation is retreating rather than reorganising, that all emerging economies remain hostage to the dollar cycle, and that EM companies are mere imitators rather than innovators. We believe these are low-probability bets.

The evidence points the other way: EMs are reorganising trade corridors, building resilience in local funding and currencies, and producing companies of global calibre. These are not fragile, peripheral markets but increasingly central to how the global economy grows.

Which brings us back to our opening question: Emerging Markets, are you missing the point?

Important Information

The views expressed should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. They reflect opinion and should not be taken as statements of fact nor should any reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

This communication was produced and approved in October 2025 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of writing and may not reflect current thinking.

Potential for Profit and Loss

All investment strategies have the potential for profit and loss, your or your clients’ capital may be at risk. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

This communication contains information on investments which does not constitute independent research. Accordingly, it is not subject to the protections afforded to independent research, but is classified as advertising under Art 68 of the Financial Services Act (‘FinSA’) and Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned.

All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co and is current unless otherwise stated.

The images used in this communication are for illustrative purposes only.

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is an Authorised Corporate Director of OEICs.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides investment management and advisory services to non-UK Professional/Institutional clients only. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited are authorised and regulated by the FCA in the UK.

Persons resident or domiciled outside the UK should consult with their professional advisers as to whether they require any governmental or other consents in order to enable them to invest, and with their tax advisers for advice relevant to their own particular circumstances.

Financial Intermediaries

This communication is suitable for use of financial intermediaries. Financial intermediaries are solely responsible for any further distribution and Baillie Gifford takes no responsibility for the reliance on this document by any other person who did not receive this document directly from Baillie Gifford.

Europe

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Ltd (BGE) is authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland as an AIFM under the AIFM Regulations and as a UCITS management company under the UCITS Regulation. BGE also has regulatory permissions to perform Individual Portfolio Management activities. BGE provides investment management and advisory services to European (excluding UK) segregated clients. BGE has been appointed as UCITS management company to the following UCITS umbrella company; Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc. BGE is a wholly owned subsidiary of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, which is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and Baillie Gifford & Co are authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Hong Kong

Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and holds a Type 1 license from the Securities & Futures Commission of Hong Kong to market and distribute Baillie Gifford’s range of collective investment schemes to professional investors in Hong Kong. Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 can be contacted at Suites 2713-2715, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong. Telephone +852 3756 5700.

South Korea

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is licensed with the Financial Services Commission in South Korea as a cross border Discretionary Investment Manager and Non-discretionary Investment Adviser.

Japan

Mitsubishi UFJ Baillie Gifford Asset Management Limited (‘MUBGAM’) is a joint venture company between Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Banking Corporation and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. MUBGAM is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Australia

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited (ARBN 118 567 178) is registered as a foreign company under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and holds Foreign Australian Financial Services Licence No 528911. This material is provided to you on the basis that you are a “wholesale client” within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (“Corporations Act”). Please advise Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited immediately if you are not a wholesale client. In no circumstances may this material be made available to a “retail client” within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act. This material contains general information only. It does not take into account any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs.

South Africa

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered as a Foreign Financial Services Provider with the Financial Sector Conduct Authority in South Africa.

North America

Baillie Gifford International LLC is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited; it was formed in Delaware in 2005 and is registered with the SEC. It is the legal entity through which Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides client service and marketing functions in North America. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered with the SEC in the United States of America.

The Manager is not resident in Canada, its head office and principal place of business is in Edinburgh, Scotland. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is regulated in Canada as a portfolio manager and exempt market dealer with the Ontario Securities Commission ('OSC'). Its portfolio manager licence is currently passported into Alberta, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Newfoundland & Labrador whereas the exempt market dealer licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories.

Israel

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is not licensed under Israel’s Regulation of Investment Advising, Investment Marketing and Portfolio Management Law, 5755-1995 (the Advice Law) and does not carry insurance pursuant to the Advice Law. This material is only intended for those categories of Israeli residents who are qualified clients listed on the First Addendum to the Advice Law.

Singapore

Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore as a holder of a capital markets services licence to conduct fund management activities for institutional investors and accredited investors in Singapore. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, as a foreign related corporation of Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited, has entered into a cross-border business arrangement with Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited, and shall be relying upon the exemption under regulation 4 of the Securities and Futures (Exemption for Cross-Border Arrangements) (Foreign Related Corporations) Regulations 2021 which enables both Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited to market the full range of segregated mandate services to institutional investors and accredited investors in Singapore.

Legal notice

MSCI makes no express or implied warranties or representations and shall have no liability whatsoever with respect to any MSCI data contained herein. The MSCI data may not be further redistributed or used as a basis for other indexes or any securities or financial products. This report is not approved, endorsed, reviewed or produced by MSCI. None of the MSCI data is intended to constitute investment advice or a recommendation to make (or refrain from making) any kind of investment decision and may not be relied on as such.