© 2017 Natalia Fedori/Shutterstock.

All investment strategies have the potential for profit and loss, your or your clients’ capital may be at risk.

To understand how companies interact with society, look to nature.

Sea anemones are sometimes mistaken for underwater plants because their colourful tentacles sway when the creatures attach themselves to rock or coral. But in 2018, scientists reported an unusual find off Japan’s coast: a variant with a peculiar body shape that buries itself inside the holes of marine sponges.

This isn’t a parasitical attack but rather a symbiotic arrangement – a term based on the Greek word for ‘living together’. The anemones hide from predators and, in turn, use their tentacles to ward off sea slugs that would otherwise feast on the sponges.

Symbiosis is more common than you might think. Think of honeybees pollinating flowering plants or underground fungal networks passing vital nutrients between trees in a forest.

Companies and society are also mutually dependent. Firms require the support of their employees, customers and supply chain workers to thrive and grow. And a healthy society needs a flourishing economy that contributes to people’s wellbeing.

The dynamic has consequences for asset managers like us. If companies play a role in adding to inequality and other societal problems, whether deliberately or not, they create investment risks.

Equally, they create investment opportunities when they align with societal goals, such as improving access to education or tackling health inequalities.

So to invest wisely, we need to understand the impact companies have on people and communities.

Narrow focus

You might think this gives a clear starting point for those considering the S in ESG – the play of ‘social’ factors alongside ‘environmental’ and ‘governance’ matters.

But the S has come to mean almost anything and everything.

ESG rating agencies usually focus on a handful of ‘social’ factors that are relatively easy to quantify and measure. Examples include a company’s approach to health and safety, labour practices, and diversity and inclusion.

However, while these factors may tell us something about the internal workings of a business, they say less about the broader and more complex relationships it has with society at large.

Delving deeper, there are several reasons the ‘S’ in ESG is more complicated to pin down than the ‘E’:

1. Social issues have not been subject to the same regulatory drive for investors

Environmental matters are at the fore because of climate change. But there has been less urgency about social concerns. So, for example, we have not (yet) seen S-equivalents to the Financial Stability Board’s Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures or the annual UN Climate Change Conference (COP).

2. It isn’t easy to measure social impacts in numerical data

Measuring a firm’s carbon footprint or its effect on water quality is relatively simple. But it’s harder to capture its societal footprint, such as the impact of its products and services on inequality or unhealthy social behaviours.

3. It’s challenging to identify a unit of analysis for ‘society’

When measuring global warming, temperature changes are the obvious metric. But when it comes to social considerations, can you quantify changes to the rights and wellbeing of the employee, the customer, the supply chain worker, certain communities or society at large?

4. Social issues are politically contested and shaped by the norms, laws, values and cultures of individual countries

Attitudes towards inequality, diversity, and access to public services differ across borders. That means there are fewer clear-cut right or wrong answers about how to resolve them.

One example of this is the impact of video games on children’s mental health. Scientific researchers are at odds about whether their overall effect is positive or negative. Some studies indicate an adverse impact on sleep and attention. Others point to a positive relationship between confidence-building and stress relief.

Countries have taken different positions. For instance, China has limited under-18s to three gaming hours a week to combat ‘addiction’. But the US, UK and European countries have no such regulations.

While scientific research is ongoing and inconclusive, this remains a challenging S-factor to evaluate – for policymakers and investors alike.

A human rights framework

Some social factors have, however, become easier to articulate.

Over the last two decades, international investor alliances have acknowledged that many S issues are human rights-related. So they have embraced a universal set of human rights principles to assess companies’ impacts on people. These include the rights to:

- fair work

- an adequate standard of living

- education

- healthcare

- a clean environment

- peace

- development

National governments may differ in their interpretation and enforcement of these rights. But companies are increasingly expected to report on related factors, such as labour relations, employee engagement, health and safety, and diversity and inclusion.

They must also make disclosures that describe their impact on customers’ rights, including user privacy, customer welfare, product liability, and data security.

In short, the S in ESG is following the E in becoming more than a noble aspiration.

Our societal approach to investing

Baillie Gifford was an early signatory to the UN Global Compact, which provides a framework for businesses to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies, and to the UN Principles for Responsible Investment, which encourage investors to embed respect for human rights in their processes.

As Tom Walsh, a portfolio manager on the International Alpha Team, recently wrote: “We’ve focused on sustainability for years because we see opportunity, not risk: the opportunity presented by the natural alignment between sustainable activities, long-term company prospects and long-term investment returns for their capital providers.”

To that end, we endorse the investment industry’s growing understanding of societal outcomes. However, we have noticed a handful of mainstream trends that do not fully capture the complexity of related social impacts. I’ll pick out three:

1. Many business-human rights frameworks focus only on adverse impacts

Our belief:

It is just as important to identify companies with strong growth prospects that are likely to impact society positively by advancing people’s rights and wellbeing. These are the companies that improve the world.

Example:

MercadoLibre’s founders created the internet platform to democratise commerce and finance in Latin America. Its ecosystem has enabled 900,000 families to make a living by buying and selling goods online, of whom 25 per cent are women-led. Users also benefit from its low-cost payments and loans systems, which provide solutions to people who cannot access traditional credit. The firm also monitors its progress across three ‘focuses of action’: driving the entrepreneurial ecosystem, contributing to community development and reducing its environmental impact.

2. Most ESG data on S has focused on internal social issues for companies, such as labour conditions and diversity and inclusion policies

Our belief:

While there is a growing focus on analysing a company’s policies and quantifying their ‘inputs’, it is equally necessary that we examine social outcomes. That includes the external effects a company has on its customers, supply chains and broader society, as well as how social trends affect companies.

Example:

Chr. Hansen, the Danish bioscience company, supports the UN Global Compact’s principles for socially responsible business activity.

It is committed to high working standards, freedom of association and equal opportunities for its staff. But much of its efforts are focused on external social impacts. For example, its food products – which include natural food cultures, enzymes and probiotics – promote gut diversity, nutrition and improved health outcomes in society more broadly.

3. A human rights approach to S captures many – but not all – of a company’s social impacts

Our belief:

A firm’s products and services can broadly impact relationships between different groups of people. That might involve reducing or widening socioeconomic, gender, racial and other inequalities. So some of our investment teams focus on inequality as a complement to our human-rights focus.

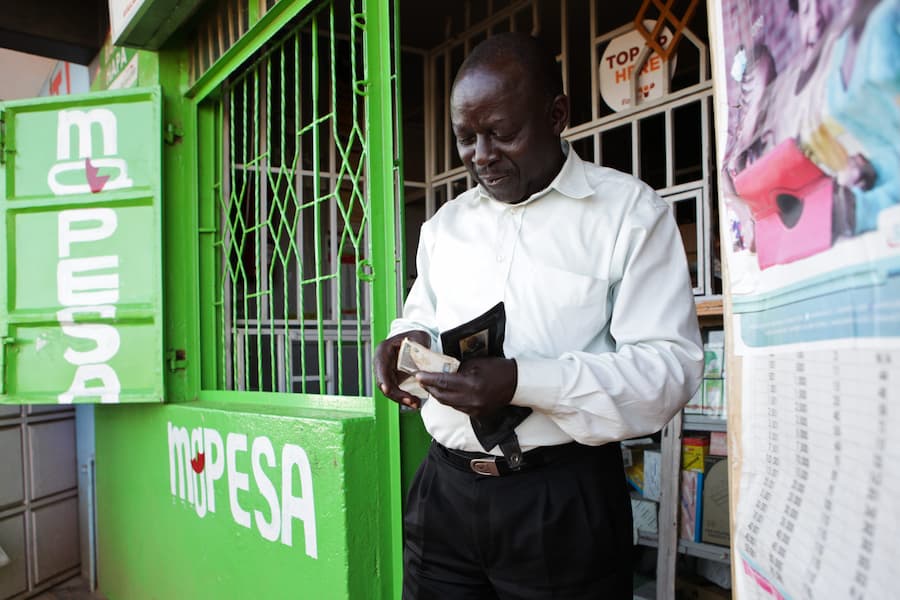

Example:

Safaricom is Kenya’s largest telecommunications company. It launched the pioneering mobile phone-based money ecosystem M-Pesa in 2007. Over the following 12 years, the percentage of Kenyans with access to formal financial services increased from 27 to 83 per cent. An MIT study in 2016 estimated that the service had helped lift 194,000 homes out of extreme poverty. That included a disproportionate number of female-headed households and rural women, to whom the formal banking sector was unavailable.

The future

As investors conducting bottom-up, long-term analysis of companies, we have long considered sustainability to be an implicit part of our process.

We have assumed that companies that positively impact society are likely to profit because they gain a competitive advantage and a ‘social licence to operate’ – the approval stakeholders, other individuals and communities give to a firm’s practices and products. In contrast, businesses that violate human rights and labour laws are less likely to be strong performers.

However, to fully evaluate social impacts, we must develop more rigorous frameworks that align with our company-by-company analysis.

ESG data has tended toward quantitative metrics that score companies on board diversity or human capital at the expense of thoughtful qualitative analysis. But many social issues can’t easily be captured by numbers. And even when they can be, we still need to carefully interpret the data and interrogate the methodology. As a result, we believe it is also vital to involve a mix of qualitative and quantitative analysis when considering social factors.

In doing so, we must push beyond common perceptions of the ‘S’ being too messy or complex to understand. We have identified three areas to help us achieve this.

First, we are building more capacity to support our research and analysis of the social impacts of companies. As part of this, we have created an Investment Human Rights Working Group to advance our understanding of human rights issues regarding existing and potential holdings. It plans to develop guidance for investment teams.

The working group’s co-chair is Tom Coutts, who is also an investment manager on the International Growth Team. He says it aims to “develop new conceptual frameworks for thinking about human rights and [to] help investors work through practical examples”. Its remit ranges from gender inequality to workers’ rights.

Second, we seek to encourage innovation within our investment teams to build social dimensions into their investment theses.

As Sally Greig, an investment manager on the Emerging Market Debt Team, says: “The ‘S’ is core to our investment thesis because of its importance to our assessment of sustainable growth. Social factors such as the security and wellbeing of individuals in emerging markets directly link to the long-term creditworthiness of these economies.”

The teams involved in each Baillie Gifford strategy have autonomy over whether and how they evaluate the social dimensions of investments. This might involve adopting distinct methods, engaging with companies and experts, and examining how social factors interact with environmental and governance issues in their holdings.

This journey will take time. But we are committed to continual improvement.

Third, we plan to have more conversations with external experts to understand the implications of business-society relations better. We are keen to broaden our community of academics, human rights lawyers, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and national and international policy experts.

This will build on existing efforts, including explorations of:

- The ethics of artificial intelligence, which the universities of Edinburgh and Cambridge are investigating with our support

- The social impact of fintechs in advancing financial inclusion, which the Brazilian research consultancy Plano CDE has been conducting for us

- The future of democracy, the welfare state and the market, which is a research project we're supporting at University College London

- Socially and environmentally sustainable transitions in the economy and society, which involves Sussex and Utrecht universities

- Reducing health inequalities and childhood poverty, which the University of Glasgow is pioneering

As Ed Whitten, a senior impact analyst and decision maker in the Positive Change Team, says: “The external research projects we’re supporting will help take our understanding and measurement of the social impact of businesses to the next level. They will enable our team to better consider social impact in our investment decisions and provide our clients with additional insights into companies we believe are delivering positive change.”

We accept that we don’t know everything.

But we aim to build our resources, enhance our understanding of the ‘S’, and continue learning from business-society relations experts.

We do this because deepening the symbiotic relationship between business and society is essential to the positive development of both.

And pursuing that goal not only puts us in a position to meet society’s needs but helps us identify companies with the best chance of delivering strong returns to our clients over the long term.

Risk Factors

The views expressed should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. They reflect opinion and should not be taken as statements of fact nor should any reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

This communication was produced and approved in December 2022 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of writing and may not reflect current thinking.

This communication contains information on investments which does not constitute independent research. Accordingly, it is not subject to the protections afforded to independent research, but is classified as advertising under Art 68 of the Financial Services Act (‘FinSA’) and Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned.

All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co and is current unless otherwise stated.

The images used in this communication are for illustrative purposes only.

Important Information

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is an Authorised Corporate Director of OEICs.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides investment management and advisory services to non-UK Professional/Institutional clients only. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited are authorised and regulated by the FCA in the UK.

Persons resident or domiciled outside the UK should consult with their professional advisers as to whether they require any governmental or other consents in order to enable them to invest, and with their tax advisers for advice relevant to their own particular circumstances.

Financial Intermediaries

This communication is suitable for use of financial intermediaries. Financial intermediaries are solely responsible for any further distribution and Baillie Gifford takes no responsibility for the reliance on this document by any other person who did not receive this document directly from Baillie Gifford.

Europe

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited provides investment management and advisory services to European (excluding UK) clients. It was incorporated in Ireland in May 2018. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited is authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland as an AIFM under the AIFM Regulations and as a UCITS management company under the UCITS Regulation. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited is also authorised in accordance with Regulation 7 of the AIFM Regulations, to provide management of portfolios of investments, including Individual Portfolio Management (‘IPM’) and Non-Core Services. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited has been appointed as UCITS management company to the following UCITS umbrella company; Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc. Through passporting it has established Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (Frankfurt Branch) to market its investment management and advisory services and distribute Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc in Germany. Similarly, it has established Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (Amsterdam Branch) to market its investment management and advisory services and distribute Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc in The Netherlands. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited also has a representative office in Zurich, Switzerland pursuant to Art. 58 of the Federal Act on Financial Institutions (“FinIA”). The representative office is authorised by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA). The representative office does not constitute a branch and therefore does not have authority to commit Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited is a wholly owned subsidiary of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, which is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and Baillie Gifford & Co are authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority.

China

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Shanghai) Limited 柏基投资管理(上海)有限公司(‘BGIMS’) is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and may provide investment research to the Baillie Gifford Group pursuant to applicable laws. BGIMS is incorporated in Shanghai in the People’s Republic of China (‘PRC’) as a wholly foreign-owned limited liability company with a unified social credit code of 91310000MA1FL6KQ30. BGIMS is a registered Private Fund Manager with the Asset Management Association of China (‘AMAC’) and manages private security investment fund in the PRC, with a registration code of P1071226.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Investment Fund Management (Shanghai) Limited

柏基海外投资基金管理(上海)有限公司(‘BGQS’) is a wholly owned subsidiary of BGIMS incorporated in Shanghai as a limited liability company with its unified social credit code of 91310000MA1FL7JFXQ. BGQS is a registered Private Fund Manager with AMAC with a registration code of P1071708. BGQS has been approved by Shanghai Municipal Financial Regulatory Bureau for the Qualified Domestic Limited Partners (QDLP) Pilot Program, under which it may raise funds from PRC investors for making overseas investments.

Hong Kong

Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and holds a Type 1 and a Type 2 license from the Securities & Futures Commission of Hong Kong to market and distribute Baillie Gifford’s range of collective investment schemes to professional investors in Hong Kong. Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 can be contacted at Suites 2713-2715, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong. Telephone +852 3756 5700.

South Korea

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is licensed with the Financial Services Commission in South Korea as a cross border Discretionary Investment Manager and Non-discretionary Investment Adviser.

Japan

Mitsubishi UFJ Baillie Gifford Asset Management Limited (‘MUBGAM’) is a joint venture company between Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Banking Corporation and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. MUBGAM is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Australia

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited (ARBN 118 567 178) is registered as a foreign company under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and holds Foreign Australian Financial Services Licence No 528911. This material is provided to you on the basis that you are a “wholesale client” within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (“Corporations Act”). Please advise Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited immediately if you are not a wholesale client. In no circumstances may this material be made available to a “retail client” within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act.

This material contains general information only. It does not take into account any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs.

South Africa

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered as a Foreign Financial Services Provider with the Financial Sector Conduct Authority in South Africa.

North America

Baillie Gifford International LLC is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited; it was formed in Delaware in 2005 and is registered with the SEC. It is the legal entity through which Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides client service and marketing functions in North America. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered with the SEC in the United States of America.

The Manager is not resident in Canada, its head office and principal place of business is in Edinburgh, Scotland. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is regulated in Canada as a portfolio manager and exempt market dealer with the Ontario Securities Commission ('OSC'). Its portfolio manager licence is currently passported into Alberta, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Newfoundland & Labrador whereas the exempt market dealer licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories. Baillie Gifford International LLC is regulated by the OSC as an exempt market and its licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (‘BGE’) relies on the International Investment Fund Manager Exemption in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec.

Israel

Baillie Gifford Overseas is not licensed under Israel’s Regulation of Investment Advising, Investment Marketing and Portfolio Management Law, 5755-1995 (the Advice Law) and does not carry insurance pursuant to the Advice Law. This material is only intended for those categories of Israeli residents who are qualified clients listed on the First Addendum to the Advice Law.