Key Points

- Iceland’s teenagers were among the biggest users of alcohol and tobacco in Europe in the 1980s and 1990s

- An effort to empower local communities to tackle the problem has used surveys answered by the youngsters to turn things round

- Icelandic consultancy Planet Youth is helping the charity Winning Scotland carry out a similar effort

Folk wisdom suggests allowing children to drink beer or wine in moderation in their early teens robs alcohol of its mystique and discourages bingeing later in life.

But Icelandic experts say they learned the hard way that this is a myth.

“If you start early on, you have a much higher risk of becoming an alcoholic or having problems with substance use later in life,” says Thorfinnur Skulason, chief communications officer for Planet Youth, a Reykjavik-based research consultancy.

“We don’t say you should never drink – that’s not what we preach. But we encourage children to postpone their first experience.”

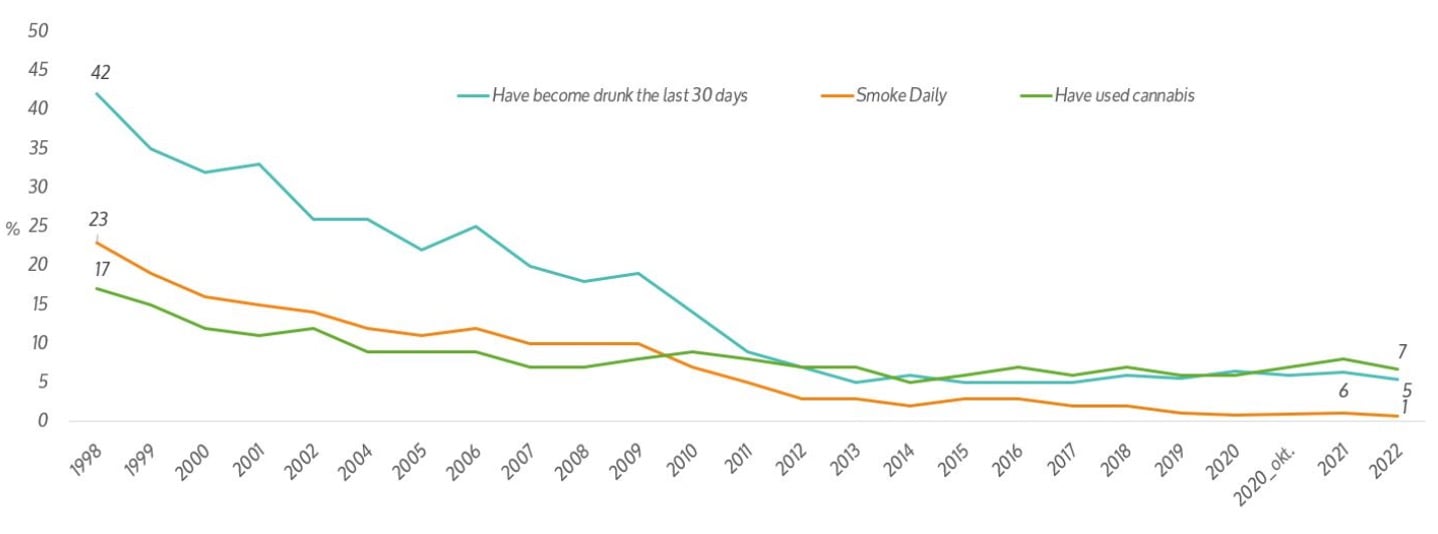

A quarter of a century ago, Iceland had some of the highest levels of substance abuse in Europe. In 1998, a study of 15- to -16-year-olds indicated about:

- two in five had got drunk in the past month

- one in five smoked daily

- one in five had used cannabis at least once

At the time, the country’s substance abuse efforts focused on teaching pupils in school about the dangers of drinks and drugs. But simultaneously, parents and other adults turned a blind eye or even encouraged them to drink elsewhere.

To tackle this, the social scientist Inga Dora Sigfusdottir founded the ICSRA (Icelandic Centre for Social Research and Analysis) in 1999. Soon after, the centre began a collaboration with the government and local municipalities to study and improve children’s wellbeing.

It takes a bottom-up approach to the problem: encouraging local communities to build networks of parents, educators and other stakeholders to find local solutions. And to help and inform them, it surveys children at least once every two years.

Iceland’s government has bolstered the initiative with changes to the law, including restrictions on under-16s being outside late at night and raising the minimum ages for tobacco and alcohol purchases. The result has been a steep and sustained decline in substance abuse.

Reported substance use among 15/16-year-old children in Iceland

Source: Planet Youth

Planet Youth helps those outside Iceland emulate its success. Recently, it partnered with Winning Scotland, a charity supported by Baillie Gifford that aims to increase young people’s resilience and confidence.

During a visit to Edinburgh, Mr Skulason met with Baillie Gifford’s Philanthropy Manager Samantha Pattman.

The conversation below has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Pattman: What was it like when you were a teenager growing up?

Skulason: The 1980s were a different world. Teenagers would try out alcohol, tobacco and other substances from about the age of 13. There was a lot of peer pressure to do so.

I remember I was 14 when I was first offered a beer. It was at a basketball tournament we’d travelled to Sweden for. After the tournament, the coaches came out and said: “OK, now we have finished, what would you like?” It was party time. And that was common. The sports body didn’t protect us from alcohol, as it would today.

I didn’t take that beer because I had a rather strict mum. But others did. They didn’t get wasted, or anything like that. But it seemed normal that we could be drinking and even should be drinking at that age.

Pattman: So how did the turnaround happen?

Skulason: The seeds were planted in the late 90s. People were getting fed up with the situation. And the politicians and municipality organisations were thinking: “What can we do?”

I would call what followed a ‘silent revolution’.

I wasn’t yet involved in Planet Youth. But as a parent, I became aware that society was demanding different things of me. The message came from schools, art, campaigns, sports organisations and other activities.

For example, my oldest daughter’s school had something called A Group of Friends. The class was divided into groups made up of five to six children. The parents took it in turns to invite other members of their child’s group to their home. Then when those children’s parents came to pick them up, they would be invited in for a coffee. We talked to each other and got to know the other kids and their parents in the group. And we felt more connected.

Children were also encouraged to participate in organised leisure activities. And parents were urged to be involved too. When I grew up and took part in a sports tournament, the parents didn’t come to watch. Today you’re expected to be there.

So although I didn’t become aware of the Icelandic Prevention Model and its strategy to reduce alcohol and drug use until later, I was aware that expectations had changed.

Pattman: And you joined Planet Youth in 2018.

Skulason: Yes. Planet Youth is effectively the export arm of ICSRA. It’s our overseas operation.

We share what has and hasn’t worked elsewhere. And we run surveys, provide progress meetings and try to measure if our partners’ efforts are having a positive effect.

Pattman: Your organisation takes a community-by-community approach to analysing risks and identifying protective measures. Can you give an example of the kind of solutions produced?

Skulason: Yes. Back in the 90s, people turned a blind eye to the fact that teenagers came totally wasted to school dances. So the schools decided to become stricter about the events and lay down some ground rules.

The school one of my daughters attended decided to create something called the ‘sober pot’. Organisers asked attendees to write their names on a piece of paper and put it into the pot. After the dancing finished, the organisers took two or three names out – it was a kind of lottery.

The picked pupils had to blow into a detection tube to show they hadn’t consumed any alcohol. And if they were clean, they received a prize. One time, my daughter won the equivalent of £90.

It was a simple act that sent out a message: it’s OK to be sober. Because there had been a lot of peer pressure to drink. And this helped to change the mindset.

Pattman: So how does the strategy work in practice?

Skulason: We provide our partners with reports from nearby schools and surrounding areas – it wouldn’t be useful to hand them information from other parts of the country that might be dealing with different problems.

One important thing is that we disseminate the results through schools – we call parents in to hear the findings of children from that specific school. That way, you can’t as a parent say: “OK, but this isn’t true of my children…”

And we try to get the results back within eight weeks of the surveys. That’s a pretty quick turnaround.

Pattman: What kind of questions do you ask the students?

Skulason: The survey has about 70 to 80 questions. The core ones cover substance abuse and also build up a profile of their life from different angles: their family, their connections to others, their health, sleeping habits and social media use. We can also add questions to cover a particular issue if we want to explore it further.

We also place some ‘jokers’ among the questions. For example, asking whether the children use a substance that doesn’t exist, to screen out those who aren’t answering honestly.

Pattman: And all this is done anonymously without linking each child to their answers?

Skulason: Yes. That’s very important to get honest answers.

The children know each school’s results are never made public either. That could lead to benchmarking, which would attract media attention. So we always try and keep the schools’ names out of the equation and only talk externally in terms of aggregate results.

Pattman: Can you give me an example of this approach working?

Skulason: It helped us deal with vaping. We were aware of it being new on the scene in 2016 and added some questions about it then. Then in 2018’s survey, we saw there had been a drastic rise in its use across age groups.

There was a notion at the time that vaping, was trouble-free, so there weren’t strict rules about how it was advertised and promoted in stores. But we could see it was creating a new generation of nicotine addicts. So we contacted the media about this. And there was a lot of discussion in schools with the parents.

The Icelandic Medical Association subsequently spoke out against vaping, and the government ended up changing the law to ban adverts for electronic cigarettes and refills, limit their sale to over-18s and limit nicotine concentration in electronic cigarette liquids.

Now we have a different threat – teenagers are using nicotine patches. So we’re always seeing different threats emerge and bringing different generations of parents in.

Pattman: And now Planet Youth is bringing this model here in partnership with the charity Winning Scotland. You’ve already surveyed some Scottish children, I believe.

Skulason: That’s true. I can’t go into detail about the results. And it’s Winning Scotland and its partners that are responsible for deciding what initiatives to adopt.

But I can say we see that children in Scotland often start drinking alcohol and smoking tobacco at an early age. And my message is that you should try to postpone that and their use of other drugs.

Words by Leo Kelion

About

Sam joined Baillie Gifford in 2003 and worked in Event Management before moving full time into her Philanthropy role in 2018.

Ref: 25216 10013223