Key points

The value of an investment, and any income from it can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

In the following four essays they explore Japan’s digital journey.

-

Personal reflections on an emerging opportunity

-

The rise of entrepreneurialism: From kaizen to kakushin

-

Japan’s digital disruptors

-

Japan’s increasing appeal: from sakoku to kaikoku

Personal reflections on an emerging opportunity

I first encountered Japanese bureaucracy in the early 1990s. Shortly after moving to Tokyo, trying to clear a container of personal effects through customs, I was told to report to the port in person.

Bags and footwear (leather being a protected industry) and the metallurgy of certain items such as lamps were particularly closely scrutinised. The Port Authority of Yokohama needed clearance from the Bureau of Port and Harbor under the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s jurisdiction and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tokyo. Proof of prior ownership, residence and work visa were required at every stage. Finally, at the end of a process requiring visits to four separate departments and no fewer than 12 personal and corporate hanko signature stamps, my goods were released.

This was at a time when Japan still ruled the global indices. Fourteen of the 20 largest companies globally by market cap were Japanese and half of these were financials. Today the only Japanese company on that list of 20 is Toyota Motor, one of only three Japanese companies in the top 100. This simple observation is both an illustration of Japan’s 30-year stagnation and its own unique and arduous pathway towards digital transformation.

Japan spends far less than its peers on information technology. Rather than narrowing over the past 30 years, the gap appears to have widened. Just 1 per cent of Japan’s workforce comprises technology professionals, compared to 3 per cent in the US, a difference of 3.8m people.

Challenges in Japan: ICT is positioned as a cost rather than an enabler in transformations

ICT investments, nominal; 1995 = 100

Source: OECD statistics

Returning to my observations of Japan after the 1980s’ Bubble Economy, features that shaped the corporate landscape then continue to influence it now, though with diminishing effect.

The first of these was the central importance of the banks, both as the main provider of capital and an instrument of governance. Much of the enforced deleveraging of the 1990s and early 2000s came through their instruction. If companies did have an external director, he (it was almost always he) was almost certainly from the main bank. Japan retreated into a cocoon of risk-aversion in the Bubble’s aftermath. Thankfully, this influence has waned following the Global Financial Crisis and introduction of the Corporate Governance Code in 2015. Around the major banks, keiretsu or interlocking business groups controlled many aspects of business life, ensuring that affiliation came before innovation.

In the early 1990s, Japan was still greatly admired for its industrial prowess and managerial style. Words such as kaizen (continuous improvement) and horenso (an acronym for effective business communication, also a play on the Japanese for spinach) were synonymous with its success. Drawing from Brian Arthur’s influential paper ‘Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy’ (1994), Japan was captured by the vision of English economist Alfred Marshall, where products are largely substitutable and competitiveness determined by accruing the small advantages of good planning, control and hierarchy.

But the country turned out to be surprisingly ill-suited to an increasingly knowledge-centric world, one of ‘increasing returns’ from technology, where psychology, cognition and adaptation proved more important. Just 20 years ago, over 60 per cent of Japan’s entire IT spend was still going on hardware and, even today, the number remains at close to 40 per cent. As Microsoft was building Windows, Japan still boasted ten major PC makers.

Japan’s IT industry has an unusual structure of prime contractors who delegate to second and third-tier vendors. According to McKinsey, 28 per cent of Japan’s IT engineers are employed by the users, with 72 per cent working for providers. In the US, the number is 65:35 in favour of IT users. An absence of in-house IT talent and understanding has become an obstacle to digital adoption. The same McKinsey report identifies the four biggest blocks to progress as senior management; lack of understanding; lack of talent and organisational structure.

‘Galapagos Syndrome’ is the term used about Japan’s 3G ‘feature phones’, a smartphone precursor that never caught on outside Japan. The term now serves for the insularity of much Japanese technology, which doomed it to eventual extinction. Many companies rely on their own R&D rather than adopt an external solution that could effect a step change. Lack of diversity and wariness of ideas from abroad are symptoms of the syndrome. There are exceptions, of course. For example, Hiroshi Mikitani, founder and CEO of ecommerce company Rakuten, declared that, “language will open your eyes to the global,” demanding that employees used English, despite Rakuten operating almost exclusively in Japan.

Overall, although board and management diversity is improving, an overly domestic focus persists. Only 6 per cent of companies have non-Japanese board executives.

If the Global Financial Crisis ended the Japanese banking hegemony, the big challenge to its digital economy came when the tech bubble burst.

Built around the country’s primacy in hardware and memory, the weaknesses of Japan’s protected IT domain and its inflexible control and planning structures were cruelly exposed by more adaptable competitors. They proved capable of reinventing themselves and getting products and services to market more quickly. As new IT ecosystems in the US and elsewhere were forming, Japanese companies were in retreat, bleeding red ink and shedding employees as they restructured. As the world moved towards content streaming, Japanese manufacturers were still battling for supremacy in DRAM and audio-visual technology.

This was all painful to watch in the first two decades of my investment career, but catharsis is now underway. Sony is a good example of how to make a successful transition from hardware dependence to digital content ownership, registering record earnings while slashing headcount by 40 per cent over 20 years. Unable to find employment in traditional industries, more workers moved to join startups and the gradual breakdown of the shukatsu simultaneous annual hiring system led more college and school leavers to study overseas. The number of Japanese studying abroad, in decline since the 1990s, rose gradually from 2010, while inbound study continues to increase. It has helped create web-savvy, globally aware, risk-seeking entrepreneurs, able to disrupt more capital-intensive, ponderous, industrial rivals.

The logic of Brian Arthur’s ‘Increasing Returns’ paper applies to Japan as well. The country was slow off the mark with reinvention but has every opportunity to capture subsequent waves. As Professor Arthur put it:

“Digitization isn’t about the purchase of computers and communications equipment. Nor is it merely about speeding up traditional operations by computers. The economy doesn’t adopt IT, it encounters IT, and as a result creates completely new activities, and new industries.”

Examples of new industries include robotics and the internet of things, where Japan is emerging as a dominant player based on its mastery of hardware and componentry, which complement its software capability.

The Japanese Government now appears more conscious of the opportunities, characteristically applying a combination of carrot and stick. The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) warns on the one hand of a 2025 ‘digital cliff’: an economic loss of up to ¥12tr ($110bn) per year unless Japanese companies overhaul antiquated IT. On the other hand, the regulatory framework is proving more adaptive. For example, Japan was early to define and recognise digital currencies. It viewed blockchain objectively and regulated in a protective but also progressive manner. Japan leads the world in initial coin offering (ICO) listings and the yen comprises 40 per cent of Bitcoin trading. The Japan Virtual Currency Association was established in 2018 to build public trust. Evidence can also be found of thinking beyond technology to a post-information ‘Society 5.0’, taking the digital dimension to a more philosophical level.

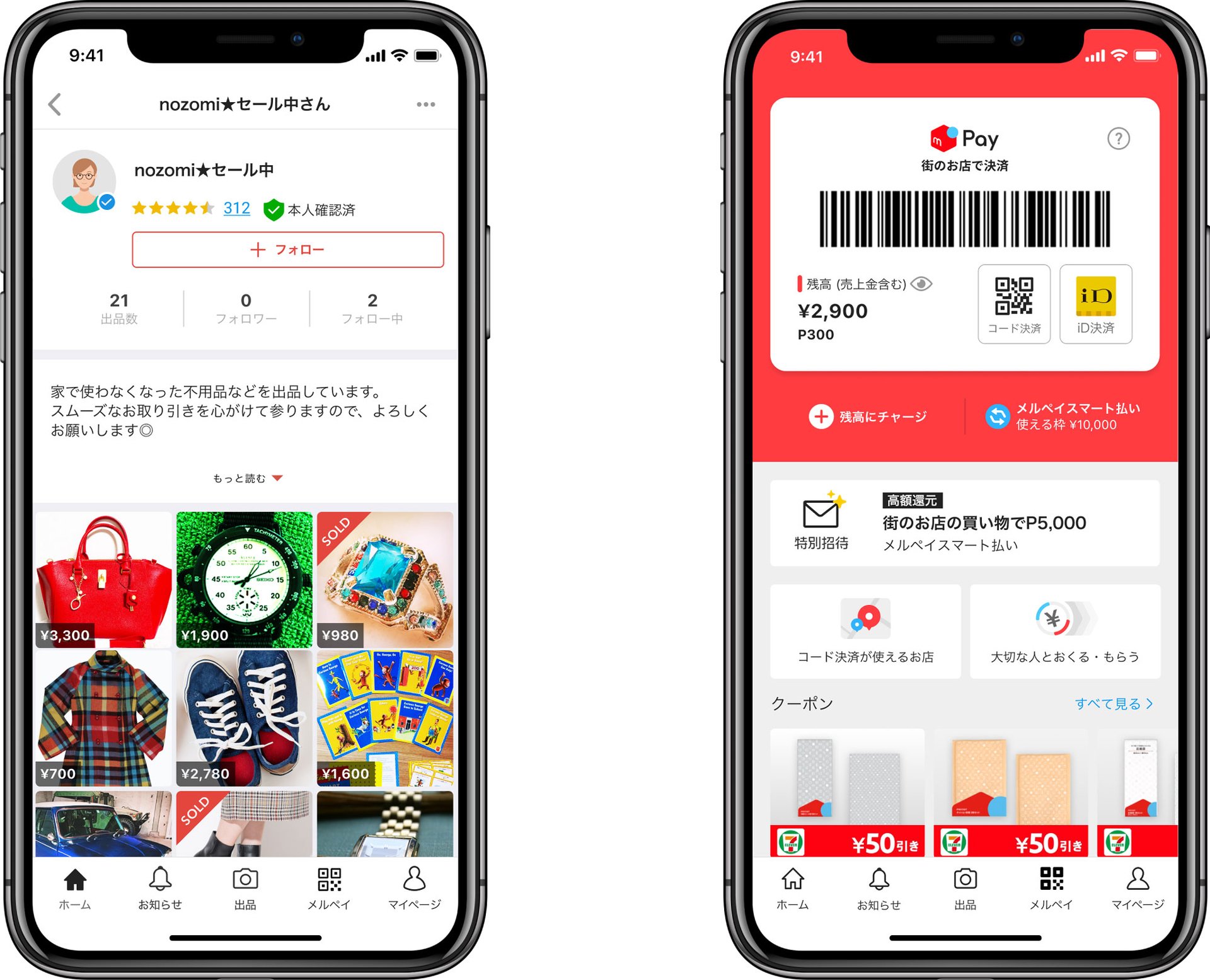

There is also the strong likelihood of different digital pathways. Japan was slow to adopt digital payments but quick to see the virtue in payment by QR-code, the square matrix bar code first developed by the automotive components giant Denso for the car industry.

The business practice of nemawashi, (laying the groundwork) through broad consultation to reach decisions, is fundamentally challenged by teleworking and video conferencing, as is the formal exchange of meishi (business cards) implying a more fundamental reappraisal of business interactions than elsewhere. E-signatory may be gaining traction across the world, but it could have a greater effect on a hanko stamp-dependent nation like Japan. My customs clearance experience would be far less arduous today. Devolved business practices and an outsized role for the middleman will create big opportunities in a digitally enabled Japan.

From an investment perspective, the Japan opportunity feels genuinely exciting. The new businesses that are transforming the landscape are often founder-run and built with entirely different approaches in mind.

While the vested interests protecting traditional Japanese ways of doing things remain formidable, the potential prizes for innovating around them are considerable – though hard to measure given that the markets often don’t yet exist. Japanese entrepreneurs are going to have to think creatively, and for the long term, if they are going to capture all the opportunities on offer.

The rise of entrepreneurialism: From kaizen to kakushin

Although Japan’s vaunted lifetime employment system can cultivate a sense of safety and stability for the salaryman, it has arguably come at a cost. It has promoted occupational segregation by creating a stark status difference between ‘regular’ and ‘non-regular’ employees; stymied specialised expertise, as generalists can be more easily reassigned within a company; and contributed to Japan’s shūshoku hyōgaki (or Ice Age Unemployment). As hiring is often frozen during periods of economic uncertainty – to protect lifetime employees – unlucky age groups can find themselves permanently locked out of the system.

Such a crisis can galvanise action, and in Japan it has proved particularly helpful in creating new and less conventional career paths for Japan’s budding entrepreneurs.

The idea of entrepreneurialism – breaking from the mould – is a serious undertaking in a society famous for conformity: ‘The nail that sticks up gets hammered down’ is a famous Japanese proverb, ‘the hawk with talent hides his talons’ is another common refrain. However, the increasingly obvious effect of digital disruption, accentuated by Covid-19, is transforming attitudes. Even conservative blue-chip companies are offering capital to start-ups operating in this space in a bid to avoid taking on the risk themselves.

Companies like Recruit and Kakaku, have also fostered ‘intrapreneurship’, incubating their own internal ventures. Overall, the start-up scene is beginning to show signs of Silicon Valley swagger, with VC deals rising several-fold in recent years, reaching a sum of $5bn in 2019. Access to risk capital allows entrepreneurs to circumvent traditional channels and avoid the suicidal hara-kiri of a premature listing, where growth prospects are often sacrificed in the pursuit of profitability.

The pandemic also helped legitimise this otherwise unorthodox career option. The psychological barrier for would-be entrepreneurs – from the fear of failure and social alienation – is beginning to break on the back of a series of homegrown success stories: Companies like Mercari, an online portal for selling used goods and Japan’s first ‘unicorn’ (an unlisted business with an estimated value of $1 billion or more); Mixi a leading mobile gaming company; WealthNavi a digital robo-wealth management platform; Freee, an accounting software provider and BASE, Japan’s version of Shopify, saw significant progress in the pandemic, and have become increasingly popular from wider press coverage.

Companies such as these, that embrace kakushin (transformative change through radical technological innovation) offer Japan contemporary answers to the analogue culture exposed by Covid.

Japan’s digital disruptors

Japan’s meteoric rise in the 1970s and 80s provoked a tide of literature on the perceived mysteries of Japanese management. The popular discourse of Nihonjinron (theories of Japaneseness) arguably began with the anthropologist Ruth Benedict’s wartime book, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, and was quickly followed by best sellers such as Chie Nakane’s Japanese Society, and Takeo Doi’s Anatomy of Dependence. These cultural studies morphed into fashionable business books, such as William Ouchi’s Theory Z: How American Business Can Meet the Japanese Challenge, which claimed to understand the secrets of Japan’s success.

Although inviting, many were accused of being ahistorical and essentialist, by presupposing that ‘The Japanese’ shared standard characteristics. This pigeonholing approach discounted the inherent diversity and complexity of Japanese society. A similar blanket approach to Japan’s digital opportunity would be equally reductive. Alleged loyalty to the fax machine notwithstanding, there are plenty of examples of innovative and ambitious companies embracing digitalisation. Gaming companies are the most conspicuous and represent a standout success story in Japan’s DX journey. As this is an industry where performance fluctuates wildly from one title to the next, companies such as Nintendo have responded by adopting a fully flexible, fabless model that embraces open innovation. By relying on its partners, in areas outside of its core competence, Nintendo can rapidly respond to the capricious needs of its audience.

There are copious examples of – domestically orientated – companies that are also embracing innovation. In healthcare, Sony-backed medical platform provider M3 wants to cut the fat from the pharmaceutical industry, by offering a transparent, accessible alternative to a plethora of intermediaries. In hospitality, Infomart is replacing a system of faxes, phone calls and paper records, by allowing restaurants to manage their fragmented supplier base online, with the additional appeal of online ordering and invoicing (a burgeoning opportunity in a country that boasts the highest number of restaurants per person, at 1 per 266 people). There is also ample room for innovation within the industrial space, as MonotaRo illustrates. It undercuts sub-scale physical store operators by selling over 18 million products online. In 2003, 70 per cent of its business was placed via fax machine. That number fell to 3 per cent last year, with over 95 per cent of orders placed online. BASE is another company benefiting from a rising tide of online consumerism, by streamlining the setting up of a virtual operation. With 98 per cent of its clients made of SMEs of five or fewer people, BASE is intent on capturing the long tail of companies set to grasp Japan’s nascent online opportunity.

Companies such as these are addressing the inefficiencies and demographic issues that beset Japan’s SMEs. This market accounts for 99.7 per cent of all businesses, and 70 per cent of the country’s employment and offers several inimitable opportunities.

Japan’s increasing appeal: from sakoku to kaikoku

In this increasingly interconnected digital world, cultural and cognitive diversity are rapidly becoming essential to success. Researchers Takahiko Masuda and Richard Nisbett highlighted trans-Pacific cultural diversity in a simple experiment where Japanese and Americans were asked to view the same underwater scene. Americans described it in detail, focusing on the three fish in the scene. The Japanese, conversely, noted the river and water first and the fish as an afterthought. For them, context came first. While the American approach was individualistic, the Japanese showed a more interdependent perspective.

According to Matthew Seyd, in his 2019 book Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, “Both offer valuable frames of reference [that when combined] create a more comprehensive grasp of reality”. The merits of cognitive diversity have become indisputable. Companies that embrace creative tension and foster fresh thinking are far more likely to remain relevant to a broader base of consumers and users.

This potentially paints a bleak picture for Japan, where an island mentality, centuries of sakoku (a ‘closed country’ rule) and a post-war ethno-nationalism have contributed to the pervasive presumption of a homogenous society unwelcoming to foreign workers: “One nation, one civilisation, one language, one culture and one race.” as a leading politician put it recently. Deep-seated attitudes regarding the subservient role of women in society, discrimination against indigenous groups and keinihon-jin (those born and raised in Japan but not seen as Japanese), along with extreme working hours and even karoshi (death from overwork), create an unwelcome advertisement to outsiders, and partly explain why only around 2 per cent of the population is foreign-born, compared with levels ranging from 10–25 per cent in western Europe and North America.

But Japan is now fostering a more inviting image. Amendments to immigration laws make it easier for gaijin (foreigners) to join Japanese companies that are themselves becoming increasingly inclusive. This is thanks in part to the progressively ambitious – and triennially revised – targets of the corporate governance code. The latest iteration raises the bar on diversity and encourages companies to embrace English. Even the Bank of Japan, the epitome of tradition, has an action plan to boost the number of female managers and double the taking of parental leave.

Covid-19 has arguably accelerated these trends, compelling companies to incorporate flexible working and family-friendly hours. Such adjustments are likely to make conventional companies more accessible, encouraging broader inclusion and diversity, from home and abroad. Of course there are companies leading the charge, like Cybozu, a software-as-a-service provider for SMEs which refuses to bow to Japan’s corporate handbook. Employees can declare their own working hours and can take up to six years’ worth of parental leave. Mercari is another example, with an increasingly cosmopolitan workforce, incorporating diversity “as a result of a quest for a better product, rather than seeing it as a goal in and of itself.” Companies like these, that clearly consider the merits of human capital, were propelled by the pandemic, and epitomise the country’s continuing pursuit of kaikoku (‘opening up to the world’).

Important information and risk factors

The views expressed in this article are those of Thomas Patchett and Donald Farquharson and should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. They reflect personal opinion and should not be taken as statements of fact nor should any reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

This communication was produced and approved in June 2021 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of writing and may not reflect current thinking.

Potential for profit and loss

All investment strategies have the potential for profit and loss, your or your clients’ capital may be at risk. Past performance is not a guide to future returns. It should not be assumed that recommendations/transactions made in the future will be profitable or will equal performance of the securities mentioned.

Stock examples

Any stock examples and images used in this article are not intended to represent recommendations to buy or sell, neither is it implied that they will prove profitable in the future. It is not known whether they will feature in any future portfolio produced by us. Any individual examples will represent only a small part of the overall portfolio and are inserted purely to help illustrate our investment style.

This article contains information on investments which does not constitute independent research. Accordingly, it is not subject to the protections afforded to independent research, but is classified as advertising under Art 68 of the Financial Services Act (‘FinSA’) and Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned.

All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co and is current unless otherwise stated.

The images used in this article are for illustrative purposes only.

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is an Authorised Corporate Director of OEICs.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides investment management and advisory services to non-UK Professional/Institutional clients only. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited are authorised and regulated by the FCA in the UK.

Persons resident or domiciled outside the UK should consult with their professional advisers as to whether they require any governmental or other consents in order to enable them to invest, and with their tax advisers for advice relevant to their own particular circumstances.

Europe

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited provides investment management and advisory services to European (excluding UK) clients. It was incorporated in Ireland in May 2018 and is authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland. Through its MiFID passport, it has established Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (Frankfurt Branch) to market its investment management and advisory services and distribute Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc in Germany. Similarly, it has established Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (Amsterdam Branch) to market its investment management and advisory services and distribute Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc in The Netherlands. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited also has a representative office in Zurich, Switzerland pursuant to Art. 58 of the Federal Act on Financial Institutions ("FinIA"). It does not constitute a branch and therefore does not have authority to commit Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited. It is the intention to ask for the authorisation by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) to maintain this representative office of a foreign asset manager of collective assets in Switzerland pursuant to the applicable transitional provisions of FinIA. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited is a wholly owned subsidiary of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, which is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co.

China

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Shanghai) Limited 柏基投资管理(上海)有限公司(‘BGIMS’) is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and may provide investment research to the Baillie Gifford Group pursuant to applicable laws. BGIMS is incorporated in Shanghai in the People’s Republic of China (‘PRC’) as a wholly foreign-owned limited liability company with a unified social credit code of 91310000MA1FL6KQ30. BGIMS is a registered Private Fund Manager with the Asset Management Association of China (‘AMAC’) and manages private security investment fund in the PRC, with a registration code of P1071226.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Investment Fund Management (Shanghai) Limited柏基海外投资基金管理(上海)有限公司(‘BGQS’) is a wholly owned subsidiary of BGIMS incorporated in Shanghai as a limited liability company with its unified social credit code of 91310000MA1FL7JFXQ. BGQS is a registered Private Fund Manager with AMAC with a registration code of P1071708. BGQS has been approved by Shanghai Municipal Financial Regulatory Bureau for the Qualified Domestic Limited Partners (QDLP) Pilot Program, under which it may raise funds from PRC investors for making overseas investments.

Hong Kong

Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and holds a Type 1 and a Type 2 license from the Securities & Futures Commission of Hong Kong to market and distribute Baillie Gifford’s range of collective investment schemes to professional investors in Hong Kong. Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 can be contacted at Suites 2713-2715, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong. Telephone +852 3756 5700.

South Korea

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is licensed with the Financial Services Commission in South Korea as a cross border Discretionary Investment Manager and Non-discretionary Investment Adviser.

Japan

Mitsubishi UFJ Baillie Gifford Asset Management Limited (‘MUBGAM’) is a joint venture company between Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Banking Corporation and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. MUBGAM is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Australia

This material is provided on the basis that you are a wholesale client as defined within s761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited (ARBN 118 567 178) is registered as a foreign company under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). It is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian Financial Services License under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) in respect of these financial services provided to Australian wholesale clients. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority under UK laws which differ from those applicable in Australia.

South Africa

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered as a Foreign Financial Services Provider with the Financial Sector Conduct Authority in South Africa.

North America

Baillie Gifford International LLC is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited; it was formed in Delaware in 2005 and is registered with the SEC. It is the legal entity through which Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides client service and marketing functions in North America. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered with the SEC in the United States of America.

The Manager is not resident in Canada, its head office and principal place of business is in Edinburgh, Scotland. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is regulated in Canada as a portfolio manager and exempt market dealer with the Ontario Securities Commission ('OSC'). Its portfolio manager licence is currently passported into Alberta, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Newfoundland & Labrador whereas the exempt market dealer licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories. Baillie Gifford International LLC is regulated by the OSC as an exempt market and its licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (‘BGE’) relies on the International Investment Fund Manager Exemption in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec.

Oman

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited (“BGO”) neither has a registered business presence nor a representative office in Oman and does not undertake banking business or provide financial services in Oman. Consequently, BGO is not regulated by either the Central Bank of Oman or Oman’s Capital Market Authority. No authorization, licence or approval has been received from the Capital Market Authority of Oman or any other regulatory authority in Oman, to provide such advice or service within Oman. BGO does not solicit business in Oman and does not market, offer, sell or distribute any financial or investment products or services in Oman and no subscription to any securities, products or financial services may or will be consummated within Oman. The recipient of this document represents that it is a financial institution or a sophisticated investor (as described in Article 139 of the Executive Regulations of the Capital Market Law) and that its officers/employees have such experience in business and financial matters that they are capable of evaluating the merits and risks of investments.

Qatar

The materials contained herein are not intended to constitute an offer or provision of investment management, investment and advisory services or other financial services under the laws of Qatar. The services have not been and will not be authorised by the Qatar Financial Markets Authority, the Qatar Financial Centre Regulatory Authority or the Qatar Central Bank in accordance with their regulations or any other regulations in Qatar.

Israel

Baillie Gifford Overseas is not licensed under Israel’s Regulation of Investment Advising, Investment Marketing and Portfolio Management Law, 5755-1995 (the Advice Law) and does not carry insurance pursuant to the Advice Law. This document is only intended for those categories of Israeli residents who are qualified clients listed on the First Addendum to the Advice Law.

52901 PRO AR 0186