Investors should consider the investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses carefully before investing. This information and other information about the Funds can be found in the prospectus and summary prospectus. For a prospectus and summary prospectus, please visit our website at bailliegifford.com/usmutualfunds Please carefully read the Fund's prospectus and related documents before investing. Securities are offered through Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC, an affiliate of Baillie Gifford Overseas Ltd and a member of FINRA.

What do human brains, cities, cells, ecosystems and business markets have in common? They are all complex systems comprised of many underlying components that dynamically interact with each other. These interactions lead these systems to have unusual properties and features. They include:

- Nonlinearity: outputs that do not scale linearly with inputs. For example, as a population of animals grows, the number of possible mating pairs increases faster.

- Emergence: system-level properties that are not present in any of the underlying parts. Think of how flocks of birds create intricate patterns of movement even though each one is following simple rules to adjust for its neighbours’ speed and position without considering the larger swarm’s shape.

- Punctuated equilibrium: long periods of relative calm interspersed with short periods of rapid change. Fossil records appear to follow this pattern, with explosions in the diversity of new species occurring after mass extinctions before more stable periods of evolutionary activity.

- Path dependence: where small changes at one point in time lead to large differences further down the road. For instance, deciding where to build bridges over a river dividing a small town can have significant ramifications for the layout of the city that it develops into centuries later.

These properties make predicting behaviour in complex systems difficult, particularly over the long term. That is why no one takes much notice of weather forecasts more than a few days out, for example.

Given the commonalities, it is possible to learn and apply lessons from complex systems in one domain to complex systems in others. This article explores how a model used in evolutionary biology might provide a helpful framework for thinking about business strategy and growth investing.

Fitness landscapes

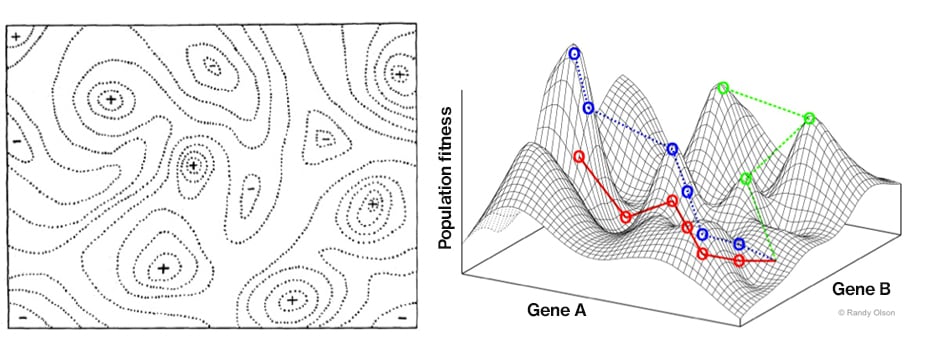

The geneticist Sewall Wright first introduced the concept of a ‘fitness landscape’ in 1932 to explain patterns of evolution. You can think of it as a grid, where each point represents a specific gene combination for a particular species. The corresponding height represents the evolutionary ‘fitness’ of each gene combination, ie the likelihood of a variant surviving and reproducing.

Modelling fitness

The image on the left shows Wright’s original two-dimensional fitness landscape – the dotted lines represent contours with respect to adaptiveness. Today, scientists use software to model three-dimensional models, as seen on the right.

Source: (left) Wright, S. “The roles of mutation, inbreeding, crossbreeding and selection in evolution” Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress of Genetics (1932), p. 358 and (right) ©Randy Olsen, Wikimedia Commons. Axes labels added, see license terms here.

Like a mountain range, fitness landscapes are characterised by lots of peaks and valleys. For a species to maximise its chances of survival, it must ‘explore’ this grid and seek out the peaks or the points of maximum fitness.

In 1991, the biophysicist Stuart Kauffman and biologist Sönke Johnsen built on this model by introducing a time variable with their concept of a ‘dancing fitness landscape’. The pair observed that fitness landscapes are not fixed. That’s because the fitness of an organism is relative: it is determined not only by its own fitness but also by the fitness of the organisms it interacts with. If the fitness of one organism in the ecosystem changes, that alters the fitness landscape for any species that interacts with it.

This echoes the ‘Red Queen effect’, inspired by the race in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, in which Alice discovers “it takes all the running you can do to keep in the same place”. The point is that it’s insufficient for a species to climb to the top of a peak and sit there. Instead, each species must move, or ‘dance’, to retain its relative fitness against a continuously shifting landscape.

There are parallels between the ecosystems we find in nature and the markets that businesses operate in. Both involve competition between entities (species in the case of ecosystems and companies in the case of business markets), which are constantly evolving (through either genetic changes or shifts in strategy) to try to maximise their fitness (reproductive success rate or profitability).

Adaptive strategies

The economist Eric Beinhocker first applied fitness landscapes to business analysis in a paper he published in 1999. Beinhocker argued that trying to make accurate predictions in a ‘complex adaptive system’ was pointless. He said that companies should avoid singular, focused strategies and instead cultivate populations of multiple, evolving strategies to account for uncertainty.

Business landscapes, just like ecosystems, are not fixed but are constantly being remodelled due to changes in competitors’ strategies and shifts in the external environment. Beinhocker compared the search for the optimal corporate strategy to that of an alpine hiker whose goal is to reach the tallest peak in a mountain range, where food is only available on the highest peaks, you can only see a few feet ahead and earthquakes periodically change the landscape. He proposed a strategy involving three key elements:

- Keep moving

A company that stands still and rests on its laurels is almost guaranteed to go backwards eventually as the environment dynamically shifts. So, the strongest and most resilient businesses ought to be restless, innovative and constantly striving to improve. - Employ parallel strategies

Natural evolution is a massively parallel process, as each organism within a species is genetically distinct. Species that lack genetic diversity are fragile and not resilient to shocks. Companies, therefore, should pursue multiple strategies simultaneously, although not necessarily with equal resources and attention. This parallelism increases the chances that one strategy will work and increases the odds that the company will survive if the environment changes – for example if a punctuated equilibrium event occurs. - Mix short and long jumps

In most fitness landscapes, the peaks and troughs are correlated and clustered. That’s because similar strategies are likely to have similar outcomes in terms of profitability. Consequently, one valuable approach to exploring the landscape is to take incremental upward steps. This is known as an adaptive walk. However, this strategy can result in companies getting stuck in ‘local maxima’ – the highest point in a local region but not in the global region. Beinhocker recommends mixing up an adaptive walk with occasional long jumps to prevent this. That is precisely what happens in nature. Random mutations are the equivalent of the adaptive walk. More radical reshuffling of the genetic deck, or long jumps, happens during sexual reproduction when genetic material is recombined.

Growth initiatives

A study by the management consultancy McKinsey, published in 1999, found that the 30 most successful companies’ business strategies aligned with Beinhocker’s recommendation of mixing short and long jumps. McKinsey called this framework ‘the three horizons of growth’.

Three horizons of growth

Source: McKinsey & Company Growth Initiative

- Horizon One strategies are the short jumps or the adaptive walk. These focus on driving growth by extending the existing core business. An example from our portfolio might be Duolingo adding additional languages to its language learning app, therefore broadening its user base.

- Horizon Two strategies are those which leverage off the core business to create new opportunities. These are medium jumps. Taking Duolingo again, this might be the incorporation of the artificial intelligence model GPT-4 into the application, which has enabled the firm to offer a higher-priced subscription tier with additional features.

- Horizon Three strategies are initiatives to create completely new businesses that do not yet exist. These are the long jumps. In Duolingo’s case, the company’s move into new subjects, including music and maths, might fall into this category.

What was most interesting about the McKinsey work was its finding that the best growth businesses tended to have strategies spread across all three of these categories, whereas average-performing growth companies were more likely to focus on Horizon One efforts.

The relative rarity of the three-pronged approach is not hugely surprising. Horizon One investments are the lowest-risk of the three and are likely to pay off in the shortest time. They are also likely to be popular internally as they strengthen the core of the business, and this is where most of the people and political capital reside within an average organisation.

The founder’s edge

Companies that are run for the short term and that worry about quarterly earnings volatility – which, in our experience, represent a substantial majority of today’s market – are likely to strongly prefer the lower-risk, shorter payoff characteristics of Horizon One.

Branching out to Horizons Two and Three requires companies to extend their timespans and embrace risk. Such an approach may also demand breaking through vested interests that oppose capital being directed away from the core.

In our experience, founder-run companies are more likely than average to pursue a diverse strategy like this. Founders are often mission-driven and are, therefore, more likely to be long-term-orientated. They also have the moral authority required to make the type of bold bets required in Horizon Three.

This may explain our long-standing observation that founder-led firms tend to be more adaptable and durable than average. The landscape that a company operates in will inevitably shift underneath it. As we have seen, the optimal strategy for staying on top in such a seismically unstable environment is a mixture of short and long hops.

We have seen many portfolio companies successfully exploit long jumps in the past. Amazon’s decision to offer cloud services as an external product is an excellent historical example. More recently, the commercial real estate information provider CoStar engaged in a long jump when it acquired Homes.com to enter the residential property listings market and compete with Zillow.

Meta (formerly known as Facebook) is another example of a holding that is not afraid to commit to efforts that may take years to reach fruition. The company’s determination to invest in its virtual and augmented reality business, Reality Labs, in the face of significant opposition from Wall Street highlights the importance of a founder’s conviction and moral authority in making tough and often controversial capital allocation decisions.

We’re looking for the companies that have the vision, patience, and ambition to make such long jumps, and founder-led businesses make up a disproportionate share of these firms.

Important information and risk factors

The Funds are distributed by Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC. Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC is registered as a broker-dealer with the SEC, a member of FINRA and is an affiliate of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co unless otherwise stated.

As with all mutual funds, the value of an investment in the Fund could decline, so you could lose money. International investing involves special risks, which include changes in currency rates, foreign taxation and differences in auditing standards and securities regulations, political uncertainty and greater volatility. These risks are even greater when investing in emerging markets. Security prices in emerging markets can be significantly more volatile than in the more developed nations of the world, reflecting the greater uncertainties of investing in less established markets and economies. Currency risk includes the risk that the foreign currencies in which a Fund’s investments are traded, in which a Fund receives income, or in which a Fund has taken a position, will decline in value relative to the U.S. dollar. Hedging against a decline in the value of currency does not eliminate fluctuations in the prices of portfolio securities or prevent losses if the prices of such securities decline. In addition, hedging a foreign currency can have a negative effect on performance if the U.S. dollar declines in value relative to that currency, or if the currency hedging is otherwise ineffective.

For more information about these and other risks of an investment in the Funds, see ‘Principal Investment Risks’ and ‘Additional Investment Strategies’ in the prospectus. There can be no assurance that the Funds will achieve their investment objectives.

The images used in this article are for illustrative purposes only.

The undernoted table shows which examples from this paper were held by Baillie Gifford at December 2023.

| Company | Baillie Gifford Share Holding in Company (% to 2dp) |

| Duolingo | 10.4 |

| Amazon | 0.39 |

| CoStar | 2.33 |

| Zillow | 1.45 |

| Meta | 0.24 |

Source: Baillie Gifford and Co.

Ref: 88460 10044322