Then aged 50, Mary Ann Sieghart was once at a dinner, sitting beside a banker who asked what she did.

She listed the political columns she wrote, the radio programmes she presented, the boards she sat on, the think tank she was chairing.

“Wow,” he breathed, “you’re a busy little girl.”

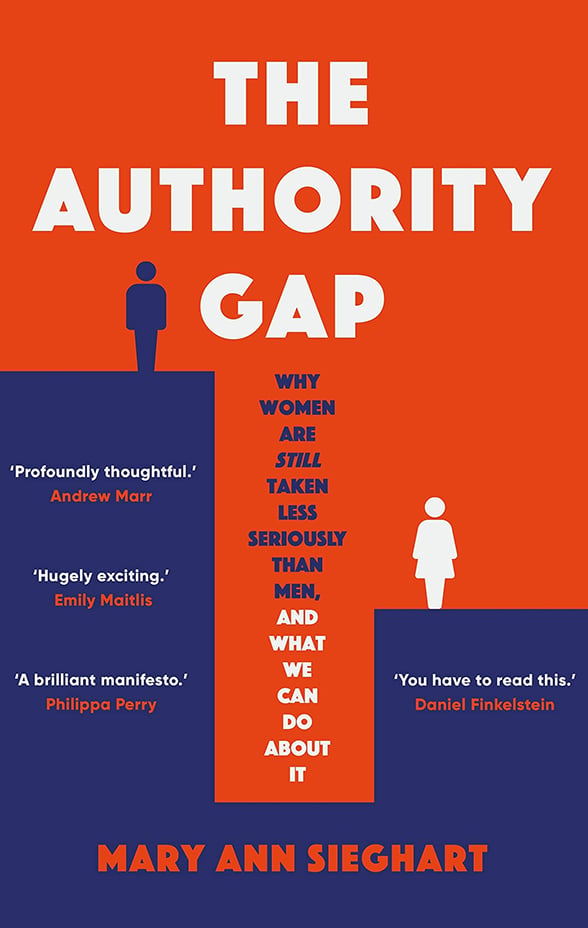

It’s an anecdote the former assistant editor of The Times recounts in The Authority Gap, adding her own voice to that of an array of high-achieving female interviewees, whose experiences in positions of authority all confirm what the entrepreneur Dame Stephanie Shirley once observed: women are patted on the head so often, it’s a wonder they don’t have flat crowns.

Dinner parties are the least of it. The Authority Gap: Why Women Are Still Taken Less Seriously Than Men, And What We Can Do About It examines the vast range of obstacles that hinder women’s professional and public expertise being respected and the resulting lack of progress. Pacey and accessible, the book is a coolly argued examination of the unconscious bias that allows the authority gap to persist, despite the opportunities now available to women.

The evidence tells us (and The Authority Gap is fastidiously supported by data) that women are just as intelligent and, she writes, if anything, better educated than men.

They are just as competent at work. Those who stay on the career ladder are just as ambitious. If they do get to the top they are, on average, better leaders. Yet they don’t win the rewards they deserve because we still instinctively underestimate women’s worth, challenge them more and promote them less. That, she argues, is what creates the authority gap.

It’s a gap recorded, sometimes depressingly, often entertainingly, by the stream of pioneering women Sieghart has interviewed for the book. They include former Supreme Court President Lady Hale, classicist Mary Beard, Oxford University Vice-Chancellor Louise Richardson, former President of Ireland Mary McAleese, author and academic Bernardine Evaristo and former Prime Minister of Australia Julia Gillard.

“One reason I wanted to interview these powerful women,” she tells me, “was that if even they have come across the authority gap, then the whole of womankind has. Even authority is no insulation.

“I talk a lot in the book about the double bind that women face with confidence and assertiveness: either we’re not confident enough and are disrespected, or we are confident enough and then disliked for being abrasive and strident.

“What almost all the women said was that they use warmth, empathy, humour, emotional intelligence, really getting to know their staff, taking them out to lunch, asking them about their families and so on to mitigate the hostility they might incur from being in charge. And interestingly, all the academic research says the same: the only way for women to navigate this narrow path is to overlay a huge amount of warmth.”

“Isn’t this the best way to lead anyway?” I ask.

“Well, exactly. Women are rated better leaders by their subordinates. But interestingly men rate themselves as better leaders.”

Ah yes. The Authority Gap comes up with lots of data proving that men do indeed think better of themselves than, to put it kindly, the evidence entirely warrants. The author puts this down to boys being taught confidence from an early age, while girls are schooled in competence. She quotes a clinical psychologist who suggests that boys get by on blagging and doing as little as possible to get parents and teachers off their backs, while the same habits that propel girls to the top of the class – their hyper-conscientiousness – may also hold them back in the workforce, encouraging them to rely on intellectual elbow grease.

So, Sieghart argues, the authority gap is real and damaging to women’s standing in the world, their pay and promotion prospects. Due to the tricks bias plays on our brains, we often don’t notice that we – women as well – are all contributing. Because men are brought up to be more confident and take up more conversational space, we incorrectly judge them to be more worthy of respect and authority.

But there is a great deal, she says, that we can do to narrow the gap. ‘No Need to Despair’ is the title of the final chapter, followed by several pages of suggested actions. I ask her for one key thing that everyone could do right now.

“Can I have two?”

“Go for it.”

“Right. The first is to be aware that, however liberal, intelligent or even female we are, we almost certainly harbour unconscious bias against women, and we can’t get rid of it or put a lid on it – it’s called unconscious for a reason. But we can notice when it manifests itself and then correct it.

“The second is: don’t mistake confidence for competence, because they are not the same thing. Men are socialised to appear more confident than women, and more likely to overestimate their competence. So, if we take people at their word, we are almost always going to assume that a man is better than a woman, even when he’s not. That lies at the root of the authority gap and the better opportunities that men get.

“And women can’t compensate by also talking themselves up, because we punish self-promoting women, while rewarding men who do it.”

This is not, as Sieghart stresses herself, a man-bashing book. Instead it attacks the attitudes we have grown up with and passed on to our children, however much we may imagine that we are doing the opposite. Convinced that I was bringing up all my children in exactly the same way, I remember being puzzled when my then three-year-old daughter begged to be allowed to wash the dishes, a suggestion that never escaped the lips of her older brothers.

“Did she perhaps see you doing the dishes?” Sieghart asks dryly.

Ah!

The book she is thinking of writing next is about what happens in childhood to create the authority gap. I’ll be reading that one too.

Ref: 27386 10016229