Key points

- Baillie Gifford's 2025 Private Investor Forum explored the complementary growth stories of China and the US

- China's evolution from manufacturer to technology innovator, led by companies such as Xiaomi, ByteDance and Alibaba, is forming an AI-enabled ecosystem to rival the west's

- The US maintains an advantage by nurturing outliers like SpaceX, NVIDIA and Aurora, private and public firms that offer exceptional growth

As with any investment, your capital is at risk.

One world, two mighty engines of innovation, enterprise and long-term growth. Attendees at Baillie Gifford’s December 2025 Private Investor Forum heard fresh perspectives on China and the US.

What follows is an edited version of the presentations at the City’s Merchant Taylors’ Hall. Qian Zhang, speaking for the Baillie Gifford China Growth Trust, made the case for a new look at China, a country whose development continues to defy outdated perceptions of it as a mere manufacturing superpower.

Following her, Paul Stevenson, speaking for Baillie Gifford US Growth Trust, explained why his team believes the US’s status as supreme disruptive innovator will remain unchallenged.

China’s changing narrative

By Qian Zhang, Investment Specialist Director, Baillie Gifford China Growth Trust

“If you want to see the future, go to China.” No, not a Chinese official or market evangelist talking, but the former chief executive of a big European multinational.

He was making the point that China is no longer simply ‘catching up’, but moving ahead, sometimes faster than expected, often in ways that unsettle old assumptions.

Earlier this year, a video circulated on Chinese social media that showed an electric car built by Xiaomi – better known for smartphones – beating a Porsche on a test track, going from zero to 100km/h in less than two seconds. The surprise wasn’t the speed, but the software – a voice-activated AI assistant, a TikTok-style interface creating a user experience that made legacy brands look dated. Ford’s chief executive described it as a “wake-up call” for the auto industry.

Alongside images of robot half-marathons in Beijing and drone coffee deliveries, there are many signals that China – the world’s second-largest economy – is now more innovative than many thought possible. Yes, there are still big concerns: state control, shifting regulation, governance and geopolitics, but China is now as much an engine of global growth as it is a source of uncertainty.

Chinese equities delivered some of the strongest returns in 2025. But assessing the country requires understanding of structural change, better understanding of the risk-reward equation and a readiness to recognise a turning point.

From retreat to reassessment

Since 2021, many global investors have slashed exposure to China or exited entirely. There were good reasons: regulatory crackdowns, a collapsing property sector, weak confidence and rising geopolitical tension. No wonder pessimism ruled.

Yet from late 2024, conditions began to change. Policy began to pivot, private enterprise regained its footing, and innovation accelerated. The question now is whether the cost of staying out is exceeding the risk of leaning back in.

Headwinds versus tailwinds

In the domestic economy, China has endured tough times. Zero-Covid restrictions proved super-disruptive, the property sector collapsed, and households saved rather than spent. Many questioned whether growth had been sacrificed for Chinese Communist Party ideology.

But since the second half of 2024, Beijing has been more pragmatic, aiming stimulus at household consumption.

There are signs that this people-not-infrastructure approach is gaining traction. Retail and services are improving, as are travel, leisure and dining. Several of China Growth Trust’s portfolio holdings reflect this trend, including Meituan, Haidilao and Luckin Coffee.

This doesn’t remove structural challenges such as the property slump and deflation. But it suggests policymakers no longer passively accept headwinds. They’re using more tools to stabilise growth.

The 2021 regulatory crackdown was a shock for investors. The halting of Ant Group’s stock market listing raised big questions about the future of private enterprise in China.

Since 2023, the tone has gradually improved. Ant and Alibaba founder Jack Ma reemerged with apparent official approval, and senior policymakers have talked up the private sector. Regulation now has clearer boundaries. We think of it as a ‘new regulatory equilibrium’ – an active state that recognises the need for private ambition, innovation and predictable rules.

Yes, there are chronic tensions with the US. Tariffs, export controls and friction over Taiwan are risks. But the US now accounts for less than 15 per cent of China’s exports and under 3 per cent of GDP. Domestic demand matters more for most Chinese companies than trade troubles.

In response to curbs on US chip exports, Chinese tech firms are building a domestic semiconductor ecosystem. Local substitution is now a long-term growth driver for some companies. It doesn’t remove geopolitical risk, but it argues for case-by-case assessment, not blanket avoidance.

China’s changing role

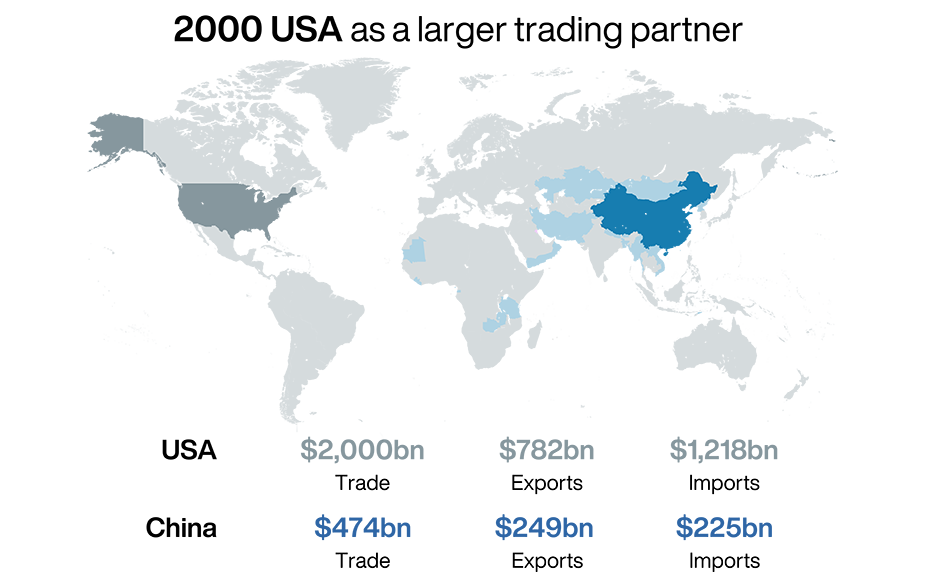

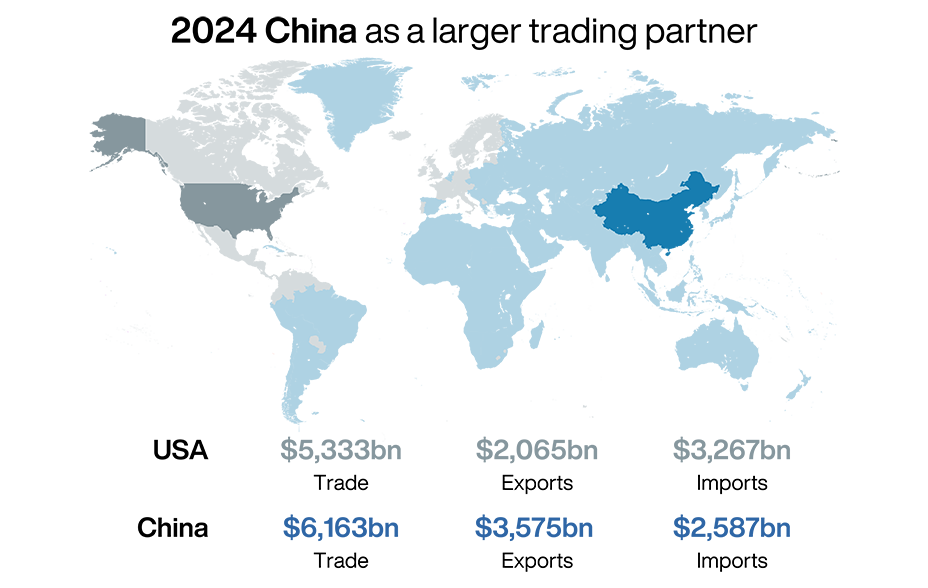

China’s role in the global economy has evolved. In 2000, the US was the dominant trading partner for most countries. By 2024, China had become the largest partner for roughly 70 per cent of the world. This reflects the rise of a multipolar system.

Sources: US Census, Customs of China and General Administration of Customs.

Exports haven’t been China’s main engine for some time. In the decade before Covid, their contribution to GDP was already declining. What is replacing them is a gradual transition towards domestic consumption, innovation and private enterprise.

Chinese households have plenty of cash stashed away. Net savings have risen sharply, creating latent purchasing power. New policy encourages spending, investment and risk-taking. Consumption is now a political priority, regulation is clearer, and entrepreneurs are actively courted.

Private firms are central to the economy, accounting for most employment, innovation and tax revenue. Symbolic moments – such as high-profile re-engagements with technology founders – signal direction in China. The intended engine of growth is no longer infrastructure, but consumers, services, modern industry and, increasingly, AI.

Innovation nation

China discussions often understate its innovation. The US leads the technological frontier and has the most complete AI ‘stack’, but China’s grassroots innovation is impressive.

DeepSeek is frequently described as China’s answer to ChatGPT. There’s support for spreading AI, from subsidised computing power to state adoption in public services and maintaining infrastructure. This matters for equities through productivity gains and improved efficiency.

The effects are already visible. Tencent’s advertising revenues have rebounded, driven by AI-enabled targeting. ByteDance’s scale now rivals US peers. Together with Alibaba, these companies form the core of China’s AI-enabled consumer ecosystem. They’re comparable in importance to Meta and Google in the US, but at far lower valuations.

China isn’t simply a manufacturing story. It’s producing globally competitive companies:

- Four of the 10 most-downloaded apps in the US are Chinese, including Temu

- China produces around 60 per cent of global electric vehicles and over 75 per cent of battery capacity

- It installs more industrial robots each year than the rest of the world combined

State-owned enterprises still dominate the index, but there are still plenty of innovative private companies. Our challenge is to spot those where potential rewards justify real risks.

Even consumer culture is shifting. Where Mickey Mouse defined American entertainment for a century, Labubu – Pop Mart’s toothy, furry doll – is a sell-out global Gen Z obsession. This is China moving up the value chain, not only in EVs and AI, but in design, intellectual property and branding.

The great disconnect

Economic gravity has shifted but investment gravity has yet to catch up. China accounts for close to 20 per cent of global GDP, yet its equities represent only around 3 per cent of the MSCI ACWI Index – less than Apple alone. In a multipolar world, this imbalance looks fragile. Even modest reallocation could have significant effects.

Understanding China, and owning it selectively, may be one of the more consequential investment decisions of the coming decade. Are we at a turning point? Very possibly. After several difficult years, performance has improved and the opportunity set looks more attractive. In simple terms, the headwinds have eased, domestic demand outweighs geopolitical uncertainty, and there are stronger opportunities for growth.

Headlines often dominate thinking about China. But long-term returns are shaped not by daily narratives but by deeper forces reshaping industries, supply chains and consumer behaviour. Those shifts rarely make the news – but that’s where opportunity lies.

Culture of creativity: why the US keeps innovating

By Paul Stevenson, Client Relationship Director, Baillie Gifford US Growth Trust

In 1903, the US government backed an ambitious attempt at powered flight, funding a prototype plane that launched from the Potomac River, immediately crashing into the water. That effort cost the equivalent of $1.8m today.

The breakthrough came instead from two bicycle mechanics in Ohio. Orville and Wilbur Wright, driven by curiosity and practical problem-solving, built the first successful powered aircraft at a fraction of the cost. Their work ignited an industry that reshaped the world.

Innovation rarely follows official plans. It emerges from restless experimentation, persistence, and people willing to question assumptions. The US has been adept at turning breakthroughs into global businesses. It’s part of the reason we believe the next generation of world-changing companies will emerge from the US, and that the US Growth Trust is well placed to capture the benefits.

Our conviction is built on four themes:

- What the US Growth Trust is designed to do

- Why the US remains such fertile ground for growth

- How we think about the drivers of future returns

- Why identifying outliers matters more than anything else

Politics, of course, looms large in the presidency of Donald Trump. Headlines are loud and policy shifts can feel consequential. But long-term investors learn to look through the noise. The companies that shape the future tend to outlast any individual administration. Capital compounds over decades, not election cycles.

The US Growth Trust was launched in 2018, the first new Baillie Gifford in 30 years. Its purpose was to give investors access to the most exciting growth businesses in the US, whether listed on public markets or still privately held.

This distinction matters. Over the past decade, US companies have stayed private for longer, choosing to scale outside public markets while they build products, cultures and competitive advantages. Much of the most powerful growth now occurs before an IPO. Capturing that growth requires a structure that can invest patiently and flexibly.

The trust can allocate up to 50 per cent of assets to private companies. Today, private holdings account for roughly 35 per cent of the portfolio – 26 companies within a total of 73. This blend allows us to invest across a company’s lifecycle, rather than being confined to the later stages.

Our edge in identifying exceptional growth businesses rests on:

- Time horizon: We invest with a genuinely long-term mindset, typically looking five-to-10 years ahead. This allows us to hold through volatility and benefit from the few companies that ultimately drive most market returns.

- Conviction-led portfolios: The trust is concentrated by design. We are genuinely active investors, prepared to own companies in meaningful size when conviction is high.

- Focus on exceptional growth: The engines of long-term value are firms that can grow revenues and earnings at exceptional rates for long periods. These businesses are rare, but they matter disproportionately.

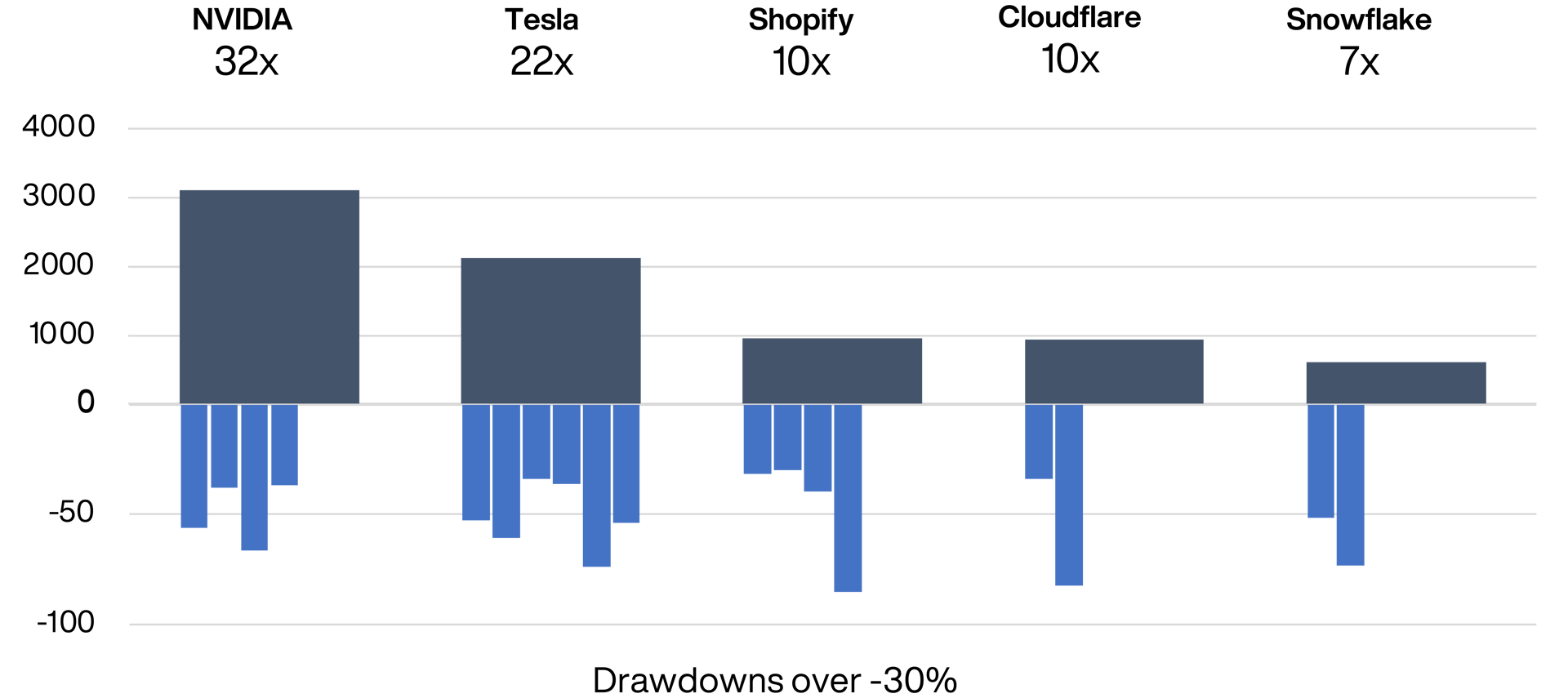

Long-term investing can be uncomfortable. Even when you identify great companies early, holding them tests conviction. The path to success is rarely smooth.

Some of the most successful investments in the trust have experienced multiple share price ‘drawdowns’ of 30 per cent or more along the way. NVIDIA has endured four such declines on its journey to a 32-fold return. Tesla has seen six. These companies look obvious in hindsight but not at the time. Patience, not prescience, proved decisive.

Patience required: the best performers suffered some of the worst slumps

Source: Revolution. Holding period returns and drawdowns since inception (23 March 2018 to 30 June 2025). US dollar. Based on selected public stocks from the US Growth Trust. Snowflake drawdowns shown from IPO in 2020.

Why the US?

At the heart of the American ideal lies a belief that individuals can build something new, take risks, and change the world through ingenuity and effort. That belief shapes institutions, incentives and behaviour and continues to make the US fertile with innovation, as the Wright brothers’ example shows.

Our task as investors is to find those points of disruption before consensus forms and to support companies as they scale great ideas into enduring enterprises.

Finding the outliers

We spend much of our time searching for outliers, starting with qualitative assessment. That means studying business fundamentals, understanding company culture, and assessing the size and shape of future markets.

Such factors are difficult to model and easy to overlook, especially when markets are focused on interest rates, inflation, geopolitics and technological hype cycles. But these things rarely determine long-term outcomes.

What matters more is:

- systemic change, such as commerce moving online

- technological change, such as the emergence of generative AI

- cultural change, such as the shift toward renewable energy

These forces reshape demand over decades. Companies positioned at their centre can grow for far longer than markets typically expect.

The US advantage

Our confidence in US equities is rooted in the history of technological change. Economist Carlotta Perez describes economic progress as a series of long technological revolutions: supercycles that transform industries and societies.

There have been five in the last 300 years:

- The Industrial Revolution

- Steam and railways

- Steel, electricity and heavy engineering

- Oil, automobiles and mass production

- Information technology

It’s significant that each revolution builds on the one before. Each requires an ecosystem capable of absorbing risk, mobilising talent, allocating capital, and commercialising breakthroughs at scale. For the past three revolutions, the US has provided the right ecosystem.

The AI revolution

We’re now at the beginning of a sixth revolution, driven by artificial intelligence. The key question is not who is experimenting with AI, but which country owns the conditions under which transformative companies can form.

The US dominates the AI ‘stack’:

- Chips: NVIDIA and its peers

- Models: OpenAI, Anthropic and others

- Infrastructure: AWS, Azure, Google Cloud

Capital follows capability. In 2024, the US attracted more than $109bn in AI-specific venture capital – over 80 per cent of global funding. This capital allows companies to scale privately for longer, reinforcing the US’s advantage.

Scale matters. For example, the US population is five times larger than the UK’s, but it has nearly 10 times as many billion-dollar startups.

The US’s infrastructural ‘flywheel’ gives it the best chance of producing the next generation of world-changing companies. It combines:

- Talent: it’s the global magnet for tech talent

- Capital: venture markets are founder-friendly

- Culture: ambition is encouraged, failure is accepted

The importance of outliers

Market returns are not evenly distributed. They are extraordinarily concentrated. As Prof Hendrik Bessembinder discovered from surveying 26,000 US between 1926 and 2016, half of all wealth created came from just 90 companies, or 0.4 per cent of the total. Most companies had a net contribution no better than Treasury bills. Wealth creation by successful companies was offset by destruction elsewhere.

In other words, most companies don’t matter. Long-term returns depend on owning a small number of extraordinary businesses. Capturing them is to search deliberately for outliers. Examples include:

- SpaceX, US Growth first invested privately in 2018. It has since transformed space economics with reusable rockets and satellite networks. In 2024, it launched 138 missions – over half of all global launches. Starlink now serves millions of subscribers worldwide. SpaceX is profitable, privately held, and valued at more than $800bn.

- Aurora, founded by veterans from Google, Tesla and Uber, is building a scalable self-driving freight platform. Since launching fully driverless operations in 2025, it has logged more than 20,000 autonomous miles. It targets a US freight market exceeding $115bn.

Capturing returns from companies like these that are leading structural shifts takes patience, conviction and a willingness to look different. But because the US is their natural home, we believe the future of growth investing remains firmly rooted there.

Annual past performance to 30 September each year (net %)

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| Baillie Gifford US Growth Trust | 20.9 | -44.7 | -15.5 | 35.4 | 34.2 |

| NAV | 33.4 | -39.0 | -5.3 | 18.7 | 32.1 |

| S&P 500 | 24.7 | 2.1 | 11.2 | 24.1 | 17.2 |

Source: Morningstar, S&P. Total return in sterling. NAV at Cum Fair. NAV: Net Asset Value.

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| Baillie Gifford China Growth Trust | -7.6 | -31.5 | -14.2 | 5.2 | 44.4 |

| NAV | 2.4 | -26.8 | -12.7 | 6.2 | 33.7 |

| MSCI China All Shares* | -2.8 | -17.4 | -8.0 | 9.7 | 25.1 |

Source: Morningstar, MSCI. Total return in sterling. NAV at Cum Fair. NAV: Net Asset Value.

*Changed from MSCI AC Asia ex Pacific index to MSCI China All Shares Index on 16/09/20. Data chain-linked from this date to form a single comparative index.

Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

Legal notice: The S&P 500 Index is the exclusive property of S&P Opco, LLC, a subsidiary of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC (“SPDJI”) and/or its affiliates. [Licensee] has contracted with SPDJI to calculate and maintain the Index. All rights reserved. Redistribution, reproduction and/or photocopying in whole or in part are prohibited without written permission of SPDJI. S&P® is a registered trademark of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC and Dow Jones® is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC. Neither SPDJI, its affiliates nor their third party licensors make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the ability of any index to accurately represent the asset class or market sector that it purports to represent, nor shall they have any liability for any errors, omissions, or interruptions of any index or the data included therein. For more information on any of SPDJI’s or its affiliate’s indices or its custom calculation services, please visit www.spdji.com.”

Legal notice: MSCI makes no express or implied warranties or representations and shall have no liability whatsoever with respect to any MSCI data contained herein. The MSCI data may not be further redistributed or used as a basis for other indexes or any securities or financial products. This report is not approved, endorsed, reviewed or produced by MSCI. None of the MSCI data is intended to constitute investment advice or a recommendation to make (or refrain from making) any kind of investment decision and may not be relied on as such.

Important information and risk factors

This communication was produced and approved in January 2026 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of writing and may not reflect current thinking.

This article does not constitute, and is not subject to the protections afforded to, independent research. Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned. The views expressed are not statements of fact and should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment.

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are listed on the London Stock Exchange and are not authorised or regulated by the FCA.

A Key Information Document is available at bailliegifford.com.

The specific risks associated with both trusts include:

- The Trusts invest in overseas securities, changes in the rates of exchange may also cause the value of your investment (and any income it may pay) to go down or up.

- Market values for securities which have become difficult to trade may not be readily available, and there can be no assurance that any value assigned to such securities will accurately reflect the price the Trust might receive upon their sale.

- The Trust can borrow money to make further investments (sometimes known as “gearing” or “leverage”). The risk is that when this money is repaid by the Trust, the value of the investments may not be enough to cover the borrowing and interest costs, and the Trust will make a loss. If the Trust's investments fall in value, any invested borrowings will increase the amount of this loss.

- The Trust can buy back its own shares. The risks from borrowing, referred to above, are increased when a trust buys back its own shares.

- The Trust can make use of derivatives which may impact on its performance.

- Investment in smaller companies is generally considered higher risk as changes in their share prices may be greater and the shares may be harder to sell. Smaller companies may do less well in periods of unfavourable economic conditions.

The specific risks associated with the Baillie Gifford China Growth Trust plc include:

- The Trust invests in China, where potential issues with market volatility, political and economic instability including the risk of market shutdown, trading, liquidity, settlement, corporate governance, regulation, legislation and taxation could arise, resulting in a negative impact on the value of your investment. Investments in China are often through contractual structures that are complex and could be open to challenge.

- Unlisted investments such as private companies can increase risk. These assets may be more difficult to sell, so changes in their prices may be greater.

- The Trust’s exposure to a single market and currency may increase risk.

- The aim of the Trust is to achieve capital growth and it is unlikely that the Trust will provide a steady, or indeed any, income.

The specific risks associated with the Baillie Gifford US Growth Trust include:

- Unlisted investments such as private companies, in which the Trust has a significant investment, can increase risk. These assets may be more difficult to sell, so changes in their prices may be greater.

All data is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co and unaudited unless otherwise stated.

185007 10059758