© Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

Please remember that the value of the investment can fall and may not get back the amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

In the mid-1980s, the ‘miracle’ of Japan’s recovery from wartime devastation was in full swing. The island nation of 120 million people that had seen steadily high growth throughout the 70s and 80s stood on the verge of an asset price and consumption-driven boom so rapid that the Tokyo Stock Exchange became – as it remains – one of the largest stock markets in the world.

The Baillie Gifford Japan Trust, launched in December 1981, had shown the way, generating several years of robust growth. By 1985, even without foreknowledge of the coming surge, the time seemed right to float a second vehicle, Baillie Gifford Shin Nippon – ‘new Japan’. It would focus on companies with revenues under ¥50bn (approximately £155m at the time), but with exciting growth potential.

Launched in May 1985, the Trust was managed at the outset by George Veitch, head of Baillie Gifford’s Japanese investments, assisted by Sarah Whitley: “26 years old with an Experimental Psychology degree from Oxford University”, the prospectus noted. Some £8m was raised via the issue of 16 million ordinary shares at 50 pence per share.

© Getty Images

The Trust’s earliest investments were an eclectic bunch. The largest holding Sankei Building was a real estate construction and investment company, a key sector in the Trust’s earliest days. Others included Teikoku Hormone, a specialist in drugs for prostate disease and Taka-Q, a menswear retailer. Another original purchase, still in the portfolio at time of writing, is Horiba, a specialist in precision measuring instruments that makes about 70 per cent of the world’s vehicle emissions testing systems. It hit the headlines when it helped expose the 2014 VW diesel emissions scandal.

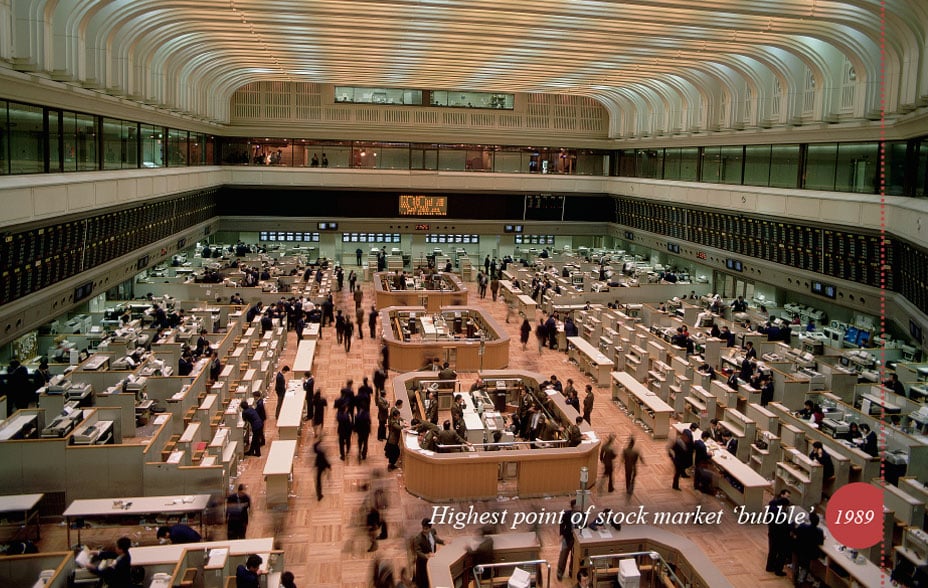

By 1989, Chairman Ian Johnstone was able to report that Shin Nippon had achieved compound annual growth of 27 per cent, while “an investment in the company when it was floated has more than doubled in value”. A year later, the Trust’s net assets (funds minus borrowings) had increased by a further 45 per cent.

But by then the Japanese bubble had become ominously bloated. The Nikkei 225 stock market index touched its peak of 38,957 in December 1989, a height unsurpassed to this day. Only three years later, more than half of that had been wiped out, with the market at just 17,000 by the end of 1992.

Japan’s ‘lost decades’ had begun. The country got stuck further in the mud after the Bank of Japan increased interest rates to slow a raging real estate market, pushing the economy into a downward spiral. Active stock selection became essential and enabled net assets to touch a new high of 158p per share in 1994, only to face new headwinds following the Kobe earthquake of January 17 1995. That disaster cost 6,434 lives, made 45,000 homeless and inflicted ¥7tn (£45bn) of damage. The Asian financial crisis of 1997, which saw currencies and stock markets slump from Thailand to South Korea, further hindered recovery.

© Corbis Historical/Getty Images

As the new millennium approached, the Trust's chair Michael Hathorn told shareholders that the Japanese economy had fallen into recession. Investment managers, to whom the correlation between economic indicators and equity prices is tenuous at best, must press on in such circumstances. It helped that Shin Nippon had bulked up on smaller companies listed in the over-the-counter (OTC) market, increasing the proportion from 7 to 21 per cent of the portfolio in 1994 to avoid, Sarah Whitley said, “the intense burden of regulation” hampering bigger companies. This proved a great call. OTC stocks surged in the closing years of the 90s, peaking at 37 per cent of the portfolio in early 2000.

Confidence had been restored, according to Whitley, by the injection of capital into the banks during 1999, government-guaranteed loans to smaller companies and a series of mergers. “Reform continues,” she added, as the Trust turned in a record 257 per cent increase in asset value over the year to 31 January 2000.

As the decade continued, the dotcom bubble caused the Japanese economy to follow the world into slowdown. Unemployment breached the 5 per cent level in 2002 for the first time in post-war Japanese history, partially because of corporate restructuring that eventually led to efficiency gains.

The middle years of a challenging decade were marked by another uplift in the Trust’s fortunes, taking total assets through the £50m barrier in 2005 and net asset value per share to a new record of 287p a year later.

But just as John MacDougall, previously Sarah Whitley’s understudy, was getting to grips with his new role as manager, the 2008 US subprime loan debacle unfolded. Despite negligible exposure to these toxic assets, Japan was hit by the worldwide trade shock as the US and Europe went into recession.

© Bloomberg/Getty Images

Three years later, MacDougall reflected that, following the near collapse of the global financial system, stimulus packages were taking effect. Global recession had been avoided and Shin Nippon had been able to buy new holdings at depressed valuations.

Against a background of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s ‘Abenomics’ reforms (flexible fiscal policy, monetary expansion, and structural economic reform), the Trust performed strongly during the post-crisis years, comfortably outperforming the MSCI Japan Small Cap Index. Success came from seeking out younger entrepreneurs with product and service innovations that rendered irrelevant the stop-start dynamics of the wider economy: companies such as medical information platform M3 (bought in 2006), online industrial parts company Monotaro (2010) and digital advertisers CyberAgent (2014). In 2017 Shin Nippon made its first private company purchase: Moneytree, a business-to-business and consumer fintech company.

By 2018, three years after the appointment of current manager Praveen Kumar, further asset gains had made Shin Nippon among the top three performers over three, five and ten years across the entire UK investment trust universe, with net assets of £401m.

As its popularity soared, managers made a series of share issues, aiding liquidity while reducing costs. In 2018, the tradability of shares was increased further via a share split in which five new shares of 2p replaced each ordinary share of 10p.

The effects of the Covid-19 crisis are still to play out, though the need for remote working and the clampdown on global travel demanded reappraisal of the research process. On the upside, lifestyle changes made in the wake of the pandemic boosted holdings that represented Japan's belated embrace of the online world. These included the digital signature and legal web portal Bengo4.com and the online food delivery business Demae-Can.

Through all these ups and downs the “spirit of Shin Nippon” was a constant. As Kumar puts it: “We seek dynamic smaller companies with the potential to grow rapidly for at least five to ten years. Typically, they’re founded and managed by young, entrepreneurial individuals willing to take short-term risks for long-term success.”

That approach served Shin Nippon well. The task ahead is not to do it differently but to keep doing it better.

Find out more about Baillie Gifford Shin Nippon Investment Trust PLC

| 1 | Amazon | 10% |

| 2 | Atlas Copco | 6% |

| 3 | Petrobras | 5% |

| 4 | Tencent | 4% |

Important Information

This communication was produced and approved in May 2023 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of presentation and may not reflect current thinking.

This communication should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. This communication contains information on investments which does not constitute independent investment research. Accordingly, it is not subject to the protections afforded to independent research and Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned. Investment markets and conditions can change rapidly and as such the views expressed should not be taken as statements of fact nor should reliance be placed on these views when making investment decisions.

Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is the authorised Alternative Investment Fund Manager and Company Secretary of the Trust.

A Key Information Document for Baillie Gifford Shin Nippon PLC is available here.

All data is source Baillie Gifford & Co unless otherwise stated.

The investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are listed UK companies. The value of their shares, and any income from them, can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount invested.

The Trust invests in overseas securities. Changes in the rates of exchange may also cause the value of your investment (and any income it may pay) to go down or up.

The Trust's exposure to a single market and currency may increase risk.

The Trust’s risk could be increased by its investment in private companies. These assets may be more difficult to sell, so changes in their prices may be greater.

The Trust can borrow money to make further investments (sometimes known as “gearing” or “leverage”). The risk is that when this money is repaid by the Trust, the value of the investments may not be enough to cover the borrowing and interest costs, and the Trust will make a loss. If the Trust’s investments fall in value, any invested borrowings

will increase the amount of this loss.

Market values for securities which have become difficult to trade may not be readily available and there can be no assurance that any value assigned to such securities will accurately reflect the price the Trust might receive upon their sale.

The Trust can make use of derivatives which may impact on its performance.

Investment in smaller immature companies is generally considered higher risk as changes in their share prices may be greater and the shares may be harder to sell. Smaller immature companies may do less well in periods of unfavourable economic conditions.

Share prices may either be below (at a discount) or above (at a premium) the net asset value (NAV). The Trust may issue new shares when the price is at a premium which will reduce the share price. Shares bought at a premium can therefore quickly lose value.

The Trust can buy back its own shares. The risks from borrowing, referred to above, are increased when a trust buys back its own shares.

The aim of the Trust is to achieve capital growth. You should not expect a significant or steady annual income from the Trust.

The Trust is listed on the London Stock Exchange and is not authorised or regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

This information has been issued and approved by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited and does not in any way constitute investment advice.

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Share Price | -5.0 | -21.2 | 68.8 | -25.2 |

-14.0 |

| NAV | -2.1 | -15.7 | 57.7 | -22.9 |

-4.9 |

| MSCI Japan Small Cap Index | -4.8 | -6.2 | 24.4 | -7.7 |

5.4 |

Performance source: Morningstar, MSCI, total return in sterling. Past performance is not a guide to future returns

Source: MSCI. MSCI makes no express or implied warranties or representations and shall have no liability whatsoever with respect to any MSCI data contained herein. The MSCI data may not be further redistributed or used as a basis for other indexes or any securities or financial products. This report is not approved, endorsed, reviewed or produced by MSCI. None of the MSCI data is intended to constitute investment advice or a recommendation to make (or refrain from making) any kind of investment decision and may not be relied on as such.