Investors should consider the investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses carefully before investing. This information and other information about the Funds can be found in the prospectus and summary prospectus. For a prospectus and summary prospectus, please visit our website at bailliegifford.com/usmutualfunds Please carefully read the Fund's prospectus and related documents before investing. Securities are offered through Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC, an affiliate of Baillie Gifford Overseas Ltd and a member of FINRA.

“It is easy to be aware of all the bad things happening in the world. It’s harder to know about the good things: billions of improvements that are never reported. Don’t misunderstand me, I’m not talking about some trivial positive news to supposedly balance out the negative. I’m talking about the fundamental improvements that are world-changing but are too slow, too fragmented or too small one-by-one to ever qualify as news. I’m talking about the secret silent miracle of human progress.”

Clients will be aware of our long-standing admiration for the work of Dr Hans Rosling. The human mind is instinctively drawn to the dramatic and the horrifying, and our tendency to notice the bad more than the good gives us an impression of a world that is more frightening, violent and hopeless than it really is. Factfulness, the book that Dr Rosling devoted the last years of his life to writing, works as a brilliant antidote to this negativity, revealing a world that is slowly but surely getting better. As Dr Rosling points out: extreme poverty has virtually been eliminated in recent decades; the gap between the developed and developing worlds has narrowed; and access to everything from clean water and electricity to education, healthcare and guitars has been transformed.1

Dr Rosling did not consider himself an optimist. He resented the label, thinking it made him sound naïve, as if he were simply replacing one misleading bias with another. Rather, Dr Rosling considered himself a very serious ‘possibilist’: someone whose belief in the possibility of further progress was based upon a clear, reasonable and fact-based assessment of all that has already been achieved. The possibilist mindset does not prevent us from acknowledging all that is bad in the world. Sometimes, terrible things happen. The possibilist mindset simply seeks to put them in their correct context: the long-established historic trend towards peace, prosperity and solutions.

We are not wide-eyed optimists, nor perma-bulls for the asset class. In nearly three decades of managing dedicated emerging market (EM) mandates, we have seen enough unexpected crises and shocks to understand that the future is uncertain. This creates anxiety, but it also creates opportunities. As investors our preference is always to embrace uncertainty rather than be paralysed by it. We will make mistakes, and we will learn from them. But we will not stop backing our judgement where we feel we might have a differentiated view. Over the long term, history suggests our mistakes will pale into insignificance against the ones that we get right.

Emerging market investors have been battered by a decade of lacklustre growth and uninspiring absolute returns. Now, as the trauma of Covid segues into the tragedy of war, we understand the temptation to fall back on linear extrapolation. But we think this would be a mistake: our contention is that there is a lot for global emerging markets (GEM) investors to be excited about. This is not about blind optimism or hope without reason. It is simply about having a clear and constructive view of what is possible.

This time is different

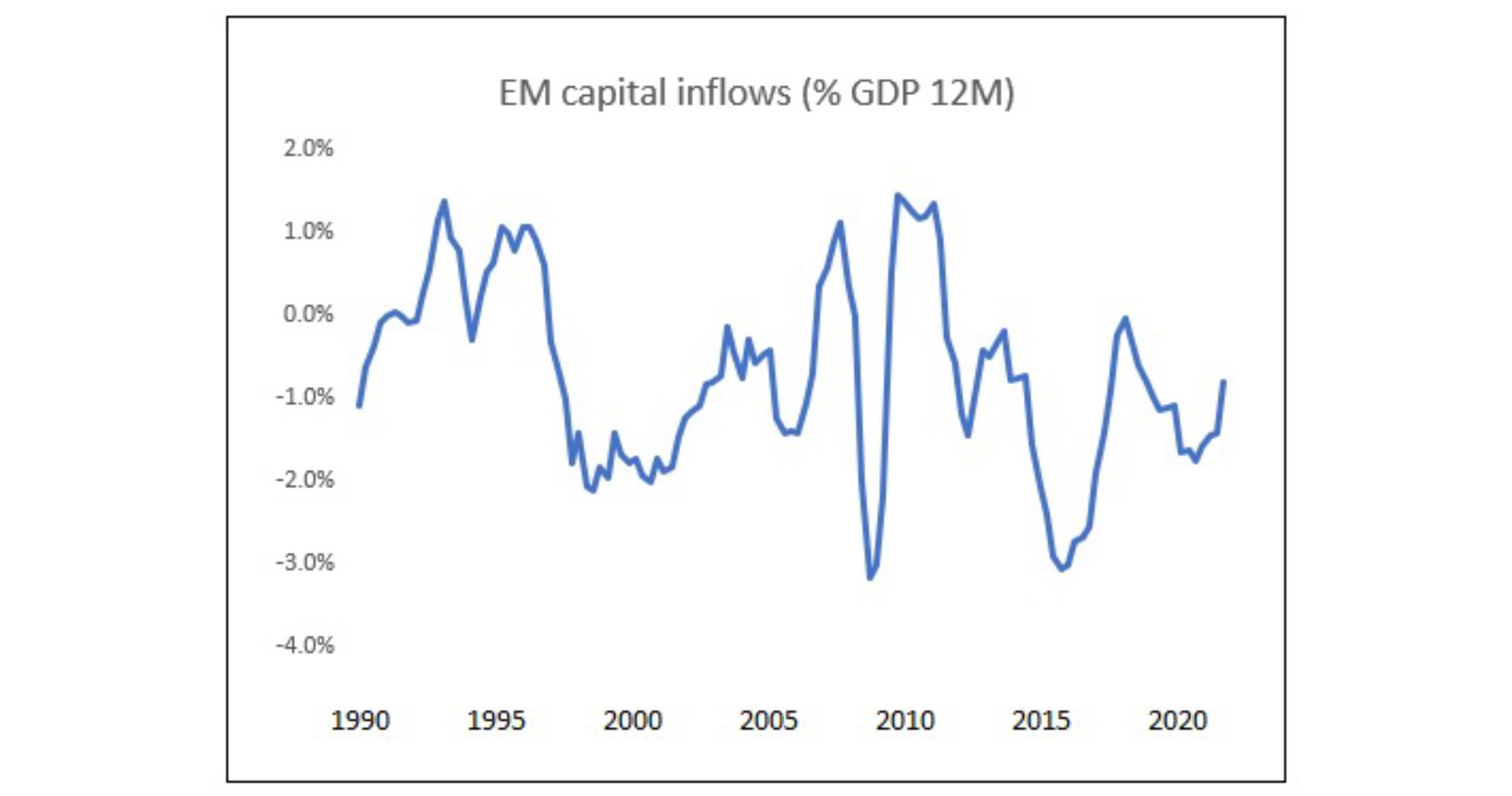

We can begin by addressing the market’s current obsession with rising inflation and interest rates, and the perception that this must be a disastrous thing for EM. It’s a seductive theory; after all, developing economies are notorious for their historic reliance on the kindness of strangers, and every EM crisis in the last 40 years has been associated with a rising federal funds rate, a dramatic tightening of liquidity, and massive capital outflows. On the other hand, there have been just as many occasions – the early 1970s, or the early 2000s, for example – when rising US interest rates caused barely a ripple in EM. We need to look at fundamentals, not blindly regurgitate market dictums.

The difference now is not just that macroeconomic resilience in EM has been transformed since the tumultuous years of the 1980s and 1990s, or even relative to the so-called ‘taper tantrum’ of the mid-2010s. The key difference now is positioning. Just look at capital flows into EM as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP): massive inflows from the early 2000s were only briefly interrupted by the financial crisis in 2008, but then reversed dramatically in 2013, and have remained in negative territory ever since. Yes, they moderated in response to the central bank easing that accompanied the pandemic shock in 2020, but they never quite made it back into positive territory. We’ve been pariahs for the best part of a decade.

So, there’s not much to see here, and certainly no looming disaster. Fine, but what about growth? Even if the west manages not to tip into recession, everyone knows that the golden age of globalisation is at an end, set to be replaced by a more fractious and balkanised era of localised production and shortening supply chains. The verdict of many commentators is that Emerging Markets – as the biggest prior beneficiaries of globalisation – will be those most challenged by its reversal.

This is a dangerous oversimplification, not to mention inconsistent with the arc of human progress. Convergence theory has always emphasised the role of crisis as a catalyst for change, and the potential for new models to emerge – what Moses Abramovitz, drawing upon Mancur Olson’s The Rise and Decline of Nations, referred to in 1986 as “radical ground-clearing experiences that open the way for new men, new organisations and new modes of operation, better fitted to technological potential”. Supply chains will continue to evolve – as they have for many years – but there are still likely to be plenty of winners in our universe even from a reshuffling based on geographic and perhaps also political contiguity. Meanwhile, the largest economies will continue to look inward for growth. Self-sufficiency, billion-plus home markets, and growing evidence that homegrown companies can capture demand previously exploited by multi-nationals listed elsewhere will continue to provide stock-pickers with long-duration growth opportunities.

We don’t wish to trivialise this debate: geopolitical shifts can be unsettling, and as we have seen this year, the costs of miscalculation can be horrific. The possibility that authoritarian governments will be increasingly spurned by western investors is one we need to take seriously, and the distinction between companies doing good things in regimes whose values are misaligned with our own is one that may be stripped of its nuance. As the decision to freeze Russian central bank reserves shows, we may be living in a multipolar world, but it remains – for now – one with a single financial system at the centre. Perhaps we will look back on this as the beginning of the end of the post-Bretton Woods era. Or perhaps, as Dr Rosling liked to remind us, those of us in North America and Europe need to understand – however much our nostalgic minds struggle with the concept – that we are becoming the 20 per cent, not the 80. Whatever the new world order might look like, however, the idea that it does not offer a sizeable and in many cases vastly expanded place for many of the countries and companies in which we invest is surely wrong.

Net zero: The New World order

The energy transition is an example of an area we are thinking hard about in this context. As clients know, we have been sympathetic to the arguments for upside surprises in the prices of several important commodities in recent years, and we have positioned our portfolios accordingly. This view has obviously become more consensual in recent months, with most analysis focusing on the near-term disruptions that are likely to result from a potential withdrawal of Russian and the Ukrainian supply from global markets. What interests us far more than this, however, is the likelihood of an acceleration in the energy security and renewable agenda.

If we are to stand a chance of meeting this agenda, we will need a lot of stuff. Wind turbines, solar arrays, energy storage, electric vehicles (EVs) and all of the associated infrastructure will not only require lots of steel and concrete, they will also require huge amounts of speciality metals and minerals such as lithium, copper, graphite, nickel, chromium and neodymium. And where are the largest, lowest-cost, most efficient and highest quality producers of this stuff? They are mostly in emerging markets.

This is well-known: most of us are probably bored of hearing that the typical EV requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car, or that an onshore wind plant requires nine times more than the gas-fired alternative.

But have the full implications of this been absorbed? Judging by the number of proposed mine projects that have been cancelled over the last year or two – partly in response to pressure from many of the same people who claim to be in favour of clean energy – perhaps not. For a bureaucratic organisation, the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) May 2021 report on the role of critical minerals in the energy transition contained an almost alarmist call-to-arms: “Today’s supply and investment plans for many critical minerals fall well short of what is needed to support an accelerated deployment of solar panels, wind turbines and electric vehicles.”2

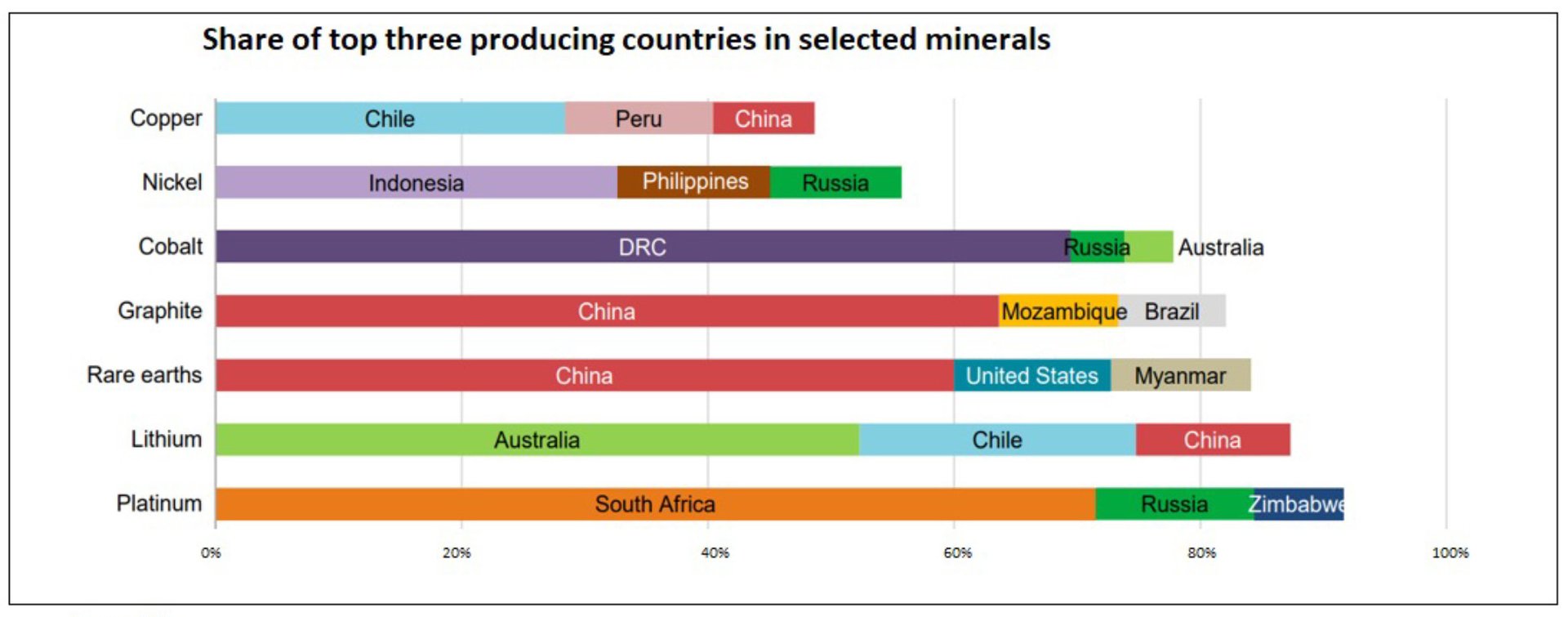

The issue is not just the shortage of current supply and the length of lead times: moving to a world of secure energy will require a massive, front-end loaded shift in trade patterns, bringing new countries and geopolitical considerations into play. For some critical transition minerals, a single country accounts for over half of worldwide production – South Africa in platinum, China in rare earth elements – while even copper and nickel have over half of current production coming from just three countries. Some of these countries are better equipped to deal with the opportunities and challenges than others: commodity windfalls distort economies, and if poorly managed, the production of mineral resources gives rise to substantial environmental and social issues.

As with all commodities, higher prices will eventually trigger a market response and incentivise innovation, and static analysis of the type undertaken by the IEA will perhaps go the same way as most Malthusian prophecies. We are already seeing this – the silver and silicon requirements of the solar supply chain have come down by about half in the last decade, while EV battery manufacturers including CATL have made enormous strides to overcome the energy density issues around lower-nickel cathode chemistries such as lithium iron phosphate (LFP). But even as markets respond, governments and investors in rich world economies need to take their responsibilities seriously, and not just bury their heads in the sand or hide behind well-meaning but counter-productive divestment policies. The need for committed, long-term and thoughtful stewardship is greater than ever, and governance rules need to acknowledge the trade-offs before it’s too late. Just one of the many sad footnotes to the invasion of Ukraine is the likelihood that our clients’ holdings in Norilsk Nickel will pass into the hands of people who care very little about the potential we saw in the company to act as a leader in the fight against climate change.

To be clear, this is not a narrow call for EM investors to buy energy and commodities at the expense of technology. The energy transition may be as important an investment theme in the coming decades as Moore’s law has been in previous decades, but they will continue to feed off each other as chips and software are added to renewable supply chains or EV platforms, while robotics, quantum computing and other as-yet unimagined industries demand more power. What is striking is just how many of these beneficiaries are in emerging markets – from the commodity producers and infrastructure providers that will build the new age, to the semiconductor companies, energy solutions providers and platforms that will power it. A barbell of exposure to these areas – a feature of our portfolios over the last five years or so – feels more appropriate than ever.

Hitting the demographic sweet spot

A favourable commodity cycle is undoubtedly helpful for large chunks of EM, and it’s surely no coincidence that elevated commodity prices have been a common feature of those historic periods when emerging markets have prospered against a backdrop rising inflation and US rates. There are even those who think that comparisons with the first ‘super-cycle’ of this century, fuelled by Chinese industrialisation, underplay what lies ahead: after all, the green transition stems from the decisions of many governments, not one.

However, the problem with commodity exports is that they tend not to generate sustainable or inclusive growth: unlike manufacturing exports, they are capital, rather than labour-intensive; relatively few jobs are created, and wealth tends to accrue disproportionately to a handful of well-connected oligarchs at the top of the tree. Usually, the most we can hope for is an upcycle that lasts perhaps three to five years, before doing our best to get out ahead of the inevitable bust. However, there is another important ‘different this time’ aspect relative to previous commodity cycles: dependency ratios.

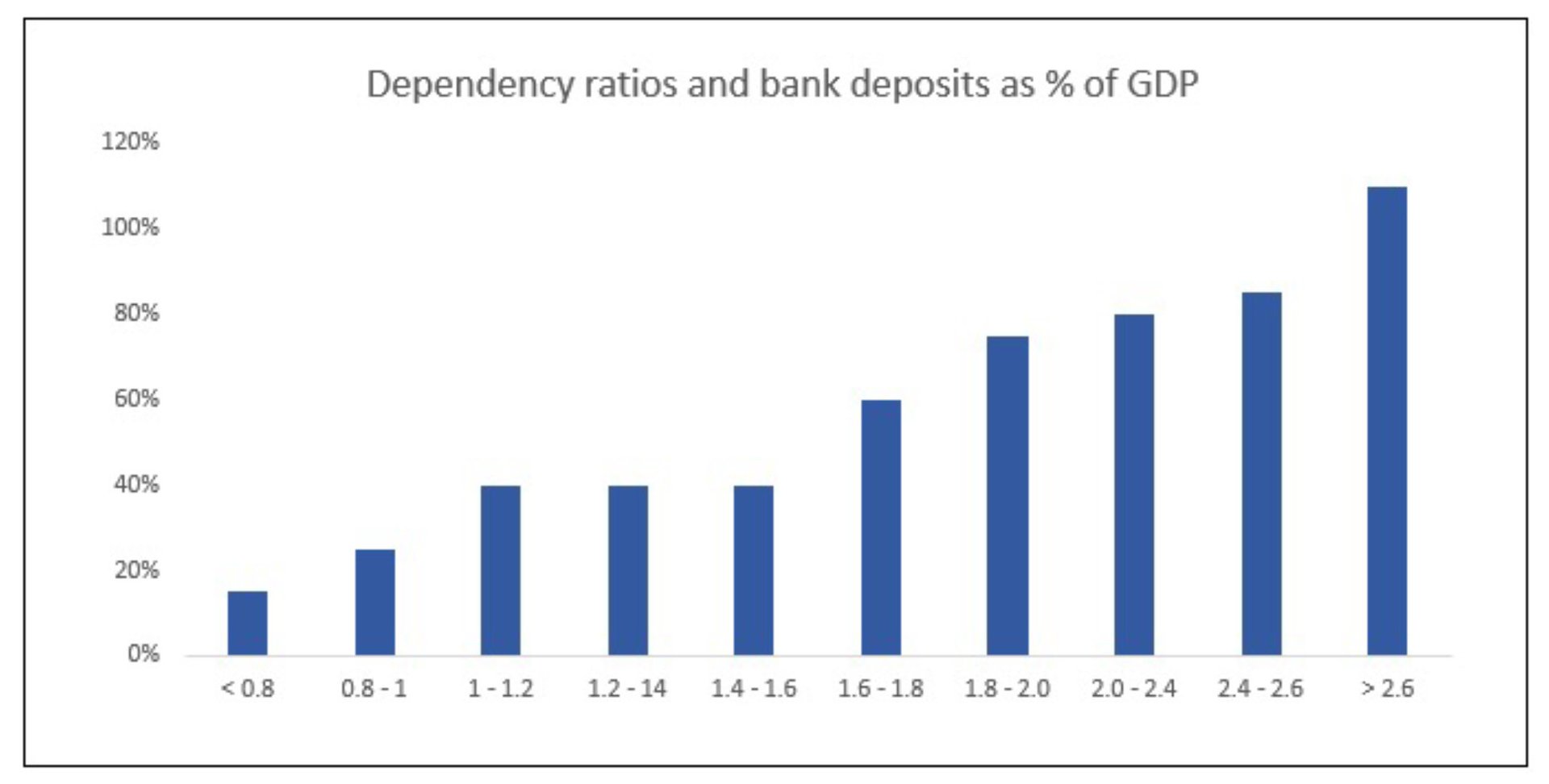

The reason that so many emerging economies in Latin America and Africa have tended to underperform those in Asia is not just down to corrupt commodity cartels or greedy banks; there’s also a close link to demographics and dependency ratios. In countries where there is a high number of children or pensioners per adult of working age, savings tend to be minimal, capital is expensive relative to labour, and interest rates tend to be high, while investment tends to be low. We can talk about fintech and financial inclusion all we like, but if you have more than three kids, you don’t have any money.

The higher the ratio of working adults to dependents, the better the banking system is equipped to fund investment needs. After all, a dependency ratio north of two is the sweet spot that North Asian economies such as South Korea have been in since the 1980s, while most of Latin America was busy lurching from one crisis to the next. However, it is exactly this sweet spot that many of the larger commodity economies in EM, such as Brazil or Indonesia, have only entered more recently. Might this filter through to lower real rates, and a much more sustainable platform for growth, than has historically been the case?

Case study: Brazil

It was once again Hans Rosling that we must thank for first drawing our attention to some of the misunderstandings around demographics in developing economies back in 2012, when we encouraged him to come to Scotland and speak at our client conference. For building on this work and highlighting the link between dependency ratios, savings and investment, we have to thank Charlie Robertson at Renaissance Capital.

Charlie is one of our favourite economists: unlike many in his field, he knows the limitations of models. At the end of last year, we asked Charlie to build upon this work with reference to a single country – Brazil – to help us answer the following question: where might nominal dollar GDP be in Brazil ten years from now, and what are the key variables that would have to go right to produce an outcome substantially higher than the current level? After all, Brazilian GDP per capita has halved in US dollar terms over the last decade, and our suspicion is that this ‘lost decade’ might be clawed back sooner than anyone expects. But as mere equity jocks, we were keen to test this ‘what if’ mindset against Charlie’s econometric rigour.

Several weeks later, Charlie sent us an email: we had achieved the unusual feat of making an economist excited. The demographic sweet spot should certainly be helpful for Brazil – the ratio of adults per dependent moved above two in 2010 and will remain there until at least 2040 – and at 80 per cent of GDP versus 40 per cent in the early 2000s, deposits are now big enough to finance growth. But if we add in the potential for an improved commodity cycle to stoke the virtuous cycle of stronger currency, lower inflation and lower real rates, and consider the possibility that human capital is now ready for an ICT revolution – hinted at by levels of educational achievement that are now much closer to OECD averages than they were in the early 2000s – the impact on growth could be profound. As Charlie wrote, “it does not require much optimism to think that GDP could rise from $1.6tn this year to $5tn by 2032”. In other words, nearly double the figure implied by IMF projections.

Of course, the exact number isn’t what matters. The point is simply to illustrate the potential for a long-term macro tailwind for Brazilian equities that could blow everyone’s expectations out of the water. Sure, Brazilian assets have started to perform a bit better amid the ‘buy anything related to commodities’ narrative of recent months, but it’s worth remembering that the MSCI Brazil is still languishing more than 50 per cent below the 2008 peak. Has the renaissance of EM’s fifth-largest market only just begun?

It’s not just China

The potential economic resurgence of countries like Brazil is important, but it’s symptomatic of a far more exciting and important trend: the emergence of new and innovative companies in parts of the world that have historically not been known for their corporate dynamism. This is the big story that no one is paying nearly enough attention to, yet it’s the one that matters most for the longer-term health of the asset class.

For the last couple of years, one of the existential questions that the asset class has been grappling with is the extent to which EM should be re-framed as ‘China’ and ‘everything else’. If you want innovative companies, you go to China. Everywhere else, it’s about surfing the cycles in an undifferentiated series of old-economy banks and miners. Should one subscribe to the narrative that China has now become ‘uninvestable’ amid regulatory tightening and darkening geopolitical clouds, then we clearly have a problem.

We’ve spent a lot of time talking about China with clients in the past year – in short, we think there’s a lot about President Xi’s agenda that makes sense in the context of the country’s broader developmental goals. While we continue to think hard about the implications and remain mindful of the risks of unintended consequences, we expect there will still be plenty of investment opportunities aligned with that agenda. But there’s a bigger story at play: China is no longer the only game in town. Indeed, one of the most encouraging developments over the last year or two is the variety of interesting and differentiated businesses from India, Brazil, Indonesia and beyond that have come onto our radar screen.

There are some commonalities: the arrival of 5G and the cloud appear to finally be democratising entrepreneurialism in many of these countries, as has already been the case in developed markets and China. It is unlikely to be a coincidence that one of the most remarkable transformations appears to be underway in India, a country that in the space of five years went from having one of the worst mobile internet infrastructures in the world to one of the best, and now also boasts the largest and fastest-growing open digital payments infrastructure in the world: last year India produced more unicorns than anywhere else in the world apart from the US and China (and based on the numbers so far this year, the country has leapfrogged China into second place). But as urban economists such as Edward Glaeser would no doubt remind us, this is really a story of cities becoming engines of their own innovation as the big numbers finally start to kick in: over half of those Indian unicorns come from Bangalore, while the rest are mostly in Gurgaon or Mumbai. The distinction between nation states and what’s happening on the ground in cities like these is a useful one to remember when we are faced with gloomy macroeconomists pontificating about the constraints placed on India’s growth potential by a lack of export manufacturing or the dependence on oil imports. Just as cities like New York were able to reinvent themselves in the twentieth century when globalisation killed off their advantages as manufacturing hubs, cities like Bangalore are reinventing themselves in the 21st century as a gateway for ideas.

1 “Culture and freedom, the goals of development, can be hard to measure, but guitars per capita is a good proxy. And boy, has that improved. With beautiful statistics like these, how can anyone say the world is getting worse?” (p64, Factfulness).

2 The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions – Analysis - IEA

Conclusions

We’ve never pretended to be any good at market forecasts; it seems a particularly pointless endeavour in the current environment. The lesson of history is that individual dislocations associated with war and pandemic can take years to normalise; we have now had both in rapid succession. As markets continue to oscillate wildly in response to every shift in the yield curve and inflation expectations, volatility will remain the only constant. That’s fine by us. We’ve been doing this through the Mexican crisis of the 1994, the Asian crisis and the Russia default of the late 1990s, the SARS epidemics of 2003, the financial crisis of 2008, the RMB devaluation and ‘taper tantrums’ of the mid-2010s. There have been times when our investment style has been in favour, and times when it has not; most of our best-performing holdings have been through 50 per cent plus drawdowns at some point along the path to multi-bagger glory. None of this will change what we do, nor alter our conviction that the only reliable driver of long-term share price performance is dollar earnings. And it is here that we find the greatest encouragement. The vast majority of the portfolio’s largest overweight positions are continuing to perform in operational terms exactly as we had hoped – in a number of cases, from TSMC to Mercadolibre, they are growing faster now than at any previous point in their history. Yet the gap between the heights we still believe them capable of achieving and what is implied by current market valuations feels very substantial indeed. Above all, we retain our optimism – however inauspicious the start, however real and troubling the problems we face – that the 2020s will be a much better decade for emerging market investors than the 2010s. Of course, we cannot predict this with certainty. But it is eminently possible.

Risk factors

The Funds are distributed by Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC. Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC is registered as a broker-dealer with the SEC, a member of FINRA and is an affiliate of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co unless otherwise stated.

As with all mutual funds, the value of an investment in the Fund could decline, so you could lose money. International investing involves special risks, which include changes in currency rates, foreign taxation and differences in auditing standards and securities regulations, political uncertainty and greater volatility. These risks are even greater when investing in emerging markets. Security prices in emerging markets can be significantly more volatile than in the more developed nations of the world, reflecting the greater uncertainties of investing in less established markets and economies. Currency risk includes the risk that the foreign currencies in which a Fund’s investments are traded, in which a Fund receives income, or in which a Fund has taken a position, will decline in value relative to the U.S. dollar. Hedging against a decline in the value of currency does not eliminate fluctuations in the prices of portfolio securities or prevent losses if the prices of such securities decline. In addition, hedging a foreign currency can have a negative effect on performance if the U.S. dollar declines in value relative to that currency, or if the currency hedging is otherwise ineffective.

For more information about these and other risks of an investment in the Funds, see "Principal Investment Risks" and "Additional Investment Strategies" in the prospectus. There can be no assurance that the Funds will achieve their investment objectives.

The images used in this article are for illustrative purposes only.

The undernoted table shows which examples from this paper were held by Baillie Gifford as at 31 March 2023.

|

Company |

Baillie Gifford Share Holding in Company (%) |

|

CATL |

0.45 |

|

TSMC |

1.20 |

|

Mercadolibre |

12.19 |

Source: Thomson Reuters.

Companies not help by Baillie Gifford: Norilsk Nickel, Renaissance Capital

ref: 44660 10020606